Thomas Jefferson. Charles Darwin. Isaac Newton.

These monumental influencers and thinkers had something in common: the practice of commonplacing. Everywhere they went, these titans of history brought a little notebook with them. Whenever inspiration struck, or whenever they saw just about anything interesting, they wrote down the event right then and there.

By actively engaging with information they would collect by observing things, and then by organizing and reflecting upon it later on, deliberately and consistently, thinkers during the Renaissance began a trend that continues to the present day in various forms.

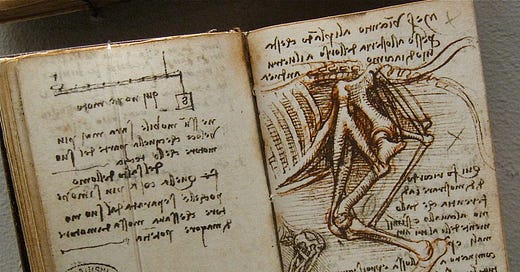

Leonardo da Vinci wasn’t officially a commonplace practitioner, but that’s mainly because he was pretty far ahead of the trend. His notebooks certainly exemplified a similar desire for knowledge collection and personal intellectual exploration—perfect examples of the Renaissance spirit of inquiry and learning.

Although Leonardo's approach was more eclectic and less structured…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Goatfury Writes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.