Differently Dumber

A friend once told me I was smarter than some other friend we both knew. This threw me for a loop.

It’s common enough for people to talk about intelligence as though it’s a value on a D&D character reference sheet, where you roll dice at the start of a campaign to determine a precise numerical value. Even as a kid, I knew this wasn’t a perfect way to measure human capacity for thought:

Intelligence is the attribute with the most baggage. I will concede that there is such a thing as absolute intelligence in a person: there are some folks who can simply hold a great deal more in their minds than I can, and they can process that information unbelievably quickly. At the same time, someone can know a vast amount about one thing and be a complete dummy in another area (trust me—for everything I’m good at, I’m equally inept at several others).

That means I can’t really talk about intelligence without simultaneously thinking about wisdom. Wisdom is the way you apply knowledge, and if this publication is about any one thing, it is surely wisdom.

Both wisdom and intelligence can be improved over time. When you’ve acquired some wisdom, you can create a sort of virtuous cycle, whereby you appreciate knowledge more. This hunger for knowledge drives you toward a better understanding of where to find new knowledge in the first place, and how to differentiate more important from less important knowledge.

Wisdom takes time, but you can also learn from the mistakes of others. The more you look around and take your time in thinking things through, the more your intelligence and wisdom will increase.

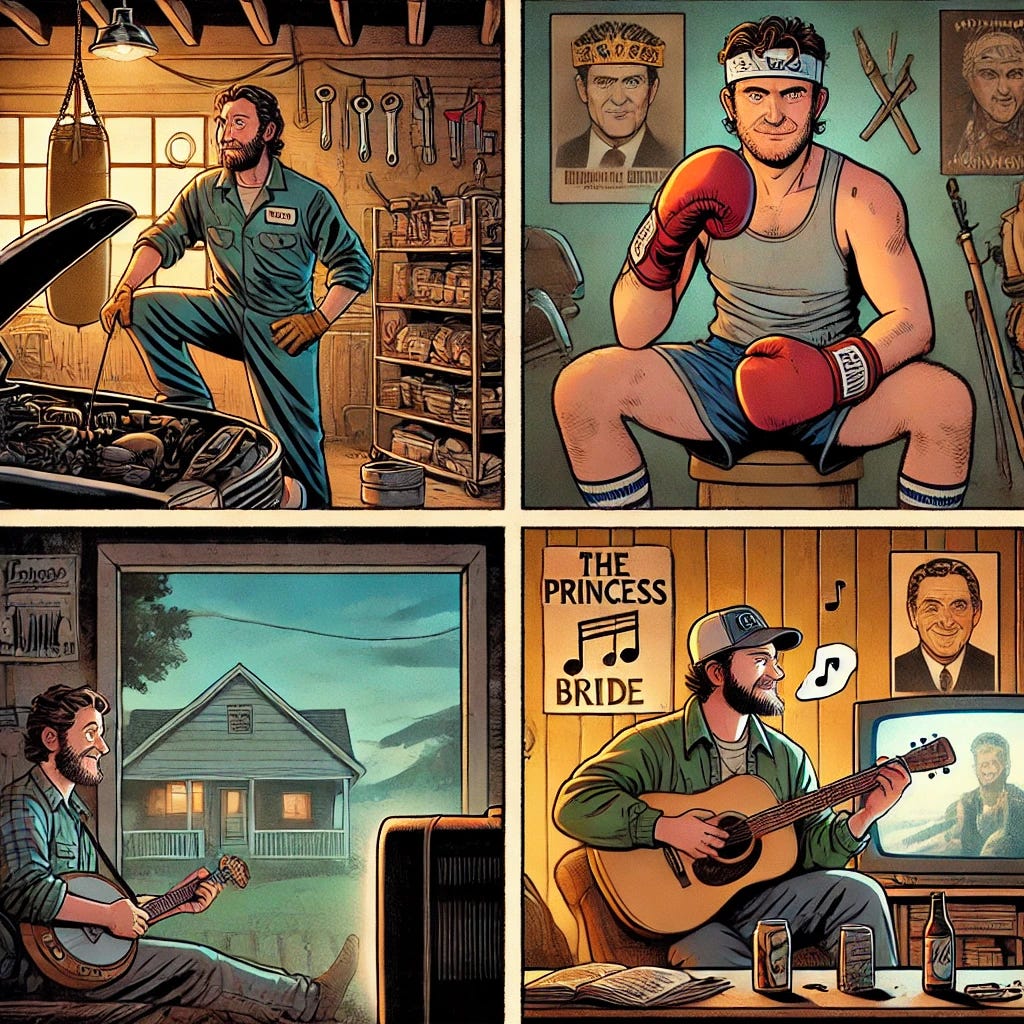

We all have these enormous packets of ignorance where another person’s knowledge eclipses our own. I stand back in awe of the expert mechanic who understand both the concepts and the details of the inner workings of cars. When I watch someone good box, I get that their knowledge of the sweet science is vastly higher than my own limited experience.

If that someone who boxes is the same person as the expert mechanic, they might know all sorts of things about bluegrass music, its history, and its traditions. Maybe they can quote every line from the Princess Bride.

I don’t have any of those bits of knowledge. Instead, I’ve cultivated a deep knowledge of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, having watched it grow up from the inside as a mere seed during the late 90s. I can quote way too many lines from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, and I know all sorts of things about punk rock music, its history, and its traditions.

A deep academic knowledge might make someone seem as though they’re untouchably smart. After all, this is more or less exactly what society tell us! Look at this smarty-farty, it says. Look at how smart this person is—we have even anointed them with fancy degrees!

What if that same academic gets lost on the way to work every day? There’s a TV show called Fringe that you may have seen, where a brilliant scientist named Walter Bishop routinely displays absent-mindedness. Now, I don’t know about you, but if I was trying to describe smart behavior, absent-minded is not the phrase that first comes to mind.

Absent-mindedness is a funny way of putting packets of ignorance, but our society does a good job of pointing this phenomenon out by way of this trope. Einstein famously didn’t want to waste any mental energy deciding what to wear for the day, so he set himself up with five identical outfits in his closet.

Einstein probably had the mental capacity to keep track of these suits, but he chose not to. He recognized that there’s a limit to what you can put inside your brain, and putting something there meant taking something away from, say, his Theory of Relativity.

In my own life, I’ve come to the conclusion that these packets of knowledge are useful, but they aren’t the end of knowledge. Instead, if you can soar a bit higher up with your thoughts, you can start to see how all of the little packets start to connect to one another.

This is where you might hear about someone being an inch deep and a mile wide, where this is intended to convey only a superficial understanding of a bunch of topics. This type of critique implies that superficial knowledge isn’t useful, but that’s far from the case.

I’ve used this water-thought analogy before. Here’s how it culminated:

That means that just as much water flows through a deep stream as through a wide stream, given equal volumes.

If that’s true—and I’m here to tell you that it is—then you have to choose to be either deep or wide. You can’t have an expert’s capacity to learn about this thing in addition to that other thing—at some point, you have to choose.

I’ve concluded that deep knowledge is useful, but wide knowledge is necessary. When you go wide, you get to see those connections I mentioned earlier. If you’re all the way down a deep rabbit hole, you might not see how it relates to another rabbit hole. This is the crux of polymathic thinking, which is just a fancy way of prioritizing width over depth.

The funny thing is that zooming out like that actually can help you dive deeper. If you become interested in why a subject is interesting in the grand scheme, suddenly it makes sense to study that subject deeply. If you happen across a mediocre rock band and obsess over them for the rest of your life, you might never even come across the Beatles.

In other words, we are all full of these packets of ignorance. We’re not smarter than one other per se, but instead, we are differently dumber.

What are your own blind spots—areas where you feel like you can’t even have a conversation with someone about a topic because you know so little? What are some areas where you have true deep knowledge?

Some of the smartest people are the dumbest people. I wonder how Einstein handled anything outside of physics?

I always liked Jack of all trades, master of some (or one).