First Principals

I remember being friends with Jabari, the son of the principal of my elementary school. I was pretty closely connected with the school since my mom was a teacher, and Jabari and I were in the same grade. We’d read The Chronicles of Narnia together after school, or turn a giant box that delivered file cabinets into a spacecraft, and we’d share our imagination.

Mr. Price was the first principal I remember, and he really set the standard high. He was always cool with the kids, never losing his temper in front of us. From what my mom tells me, his emotional intelligence among teachers was also very high.

Having the head of a school is a very old idea. In Ancient Greece, Plato’s Academy wasn’t exactly a university in the modern sense, but it certainly set the prototype. Here, great thinkers came together to devote lifetimes to working on a particular subject.

It paid to have someone thinking about all that thinking, and about who should be thinking about what. The last thing you wanted was your two best thinkers trying to solve the same problem, so having some organization was necessary.

If the Romans were good at any one thing in particular, it was copying Greek ideas and then pushing them much further along. The Romans also really liked their bureaucracy, so it started to become clear that you needed someone to act as a bridge between the academy and the outside world.

Still, these were more like small business owners than principals. They were in the business of taking money from rich people and educating their children, not in curriculum building and institutional fundraising and reporting.

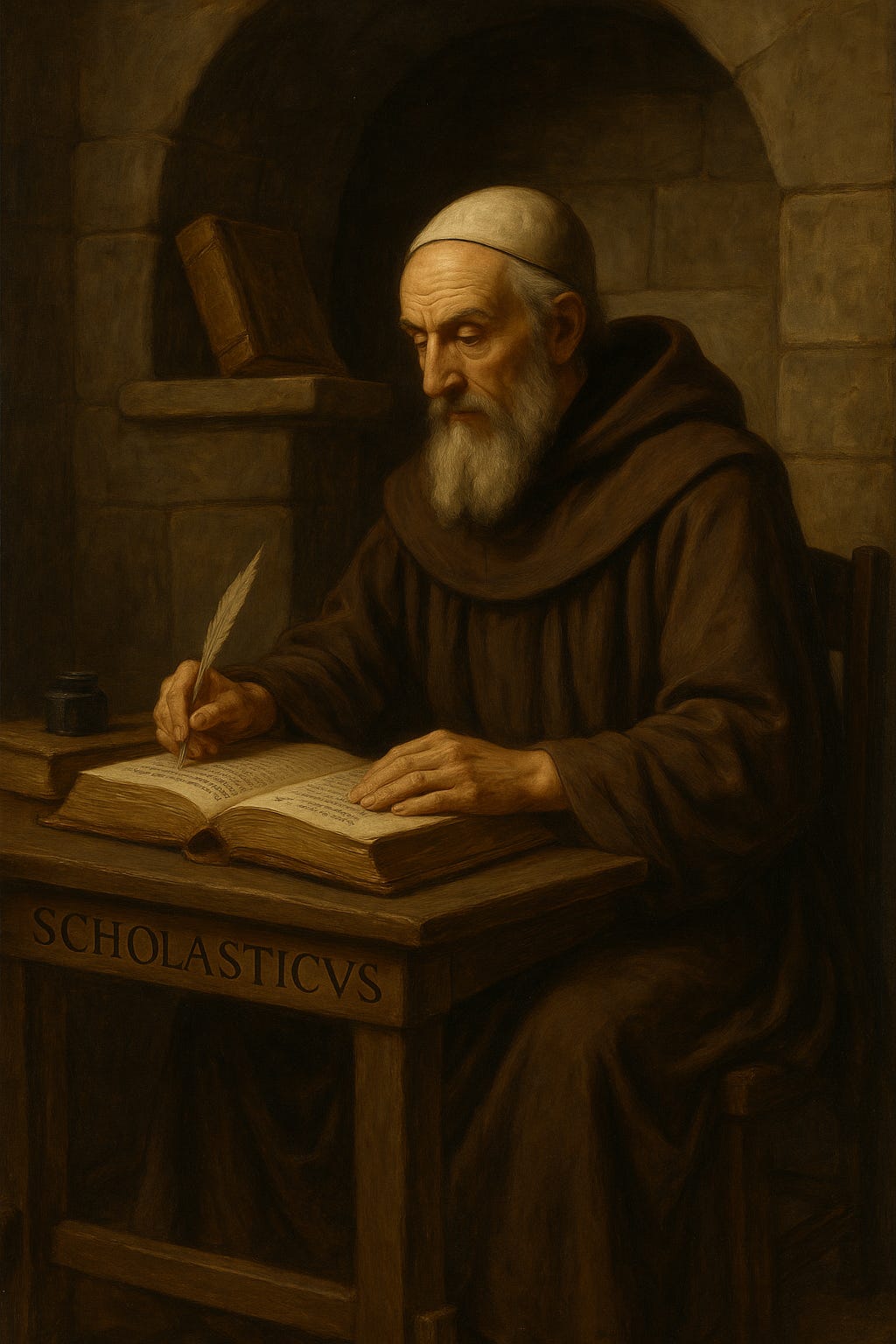

The middle ages saw the first monasteries and cathedrals spring up in Europe, and they picked up on this idea and really ran with it. If there’s anyone who liked bureaucracy more than Ancient Romans, it was these schools designed to cater to the most devout of students. Monasteries and cathedrals were really the academic centers of Europe, operating still more in the vein of colleges or universities.

The clergy would normally appoint a scholasticus to do everything the teachers weren’t doing. This was in addition to their role as teachers. They would hire or fire all the teachers and staff, and they created the curriculum—mostly about Christian doctrine, but also a fair bit of grammar and history.

The scholasticus was also responsible for maintaining discipline among the students. Here’s where your idea of a principal may really live: the disciplinarian side. I know we kids were terrified of being sent to the Principal’s office, since this was where justice would ultimately be meted out.

The Late Middle Ages saw the first formal universities, complete with deans. Unlike the scholastici, the dean had no formal teaching duties, so they could focus on the administrative tasks at hand. Deans at colleges and universities led to the idea of a headmaster at a grammar school, like you might see in a Monty Python skit or a Pink Floyd movie.

Now, these days, the headmaster is a bit of a different role than a principal. A headmaster continues the tradition of the scholasticus by being both head instructor and head administrator. A principal, by contrast, drops the academic lead title and focuses the entire role on running the show.

Interestingly enough, the word principal first shows up in print near the start of the 19th century, where it described the principal teacher. Over time, though, the teaching duties of most principals dropped off, and the admin focus took center stage.

I'm always sitting, walking, biking, and thinking.

Clever title and great piece. Dynamic mind you have 👊🏻