Francis Bacon was a 20th century painter who was born in Ireland, the product of two British parents. He was an outsider from day one.

Bacon had a tough childhood. His father, having served as a captain in the British Army, had strong authoritarian tendencies. He was that stereotypical emotionally-distant, but harsh English father—inflexible in his interpretation of morality, and rigid in his execution of punishments when necessary.

Meanwhile, young Francis suffered from severe asthma, meaning he had to be tutored at home. This kept him isolated from the other children.

Then, as a teenager, things got infinitely tougher for Francis as he discovered that he was a homosexual, something his father probably discovered shortly before throwing Francis out at age 16.

Unsurprisingly, he found a supportive community of artists and thinkers who accepted him for who he was, and Bacon’s painting career took off. Unfortunately, his life was marked by turmoil and addiction.

Over the years, Bacon embraced his sexuality and was able to express his views through art, and while his paintings were very controversial, they were also quite successful, at least from a critical and financial standpoint. Bacon lived until age 82, and it seems like the second half of his life was far better than the first half.

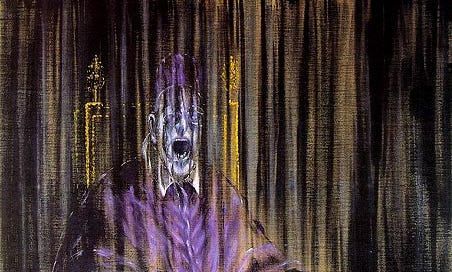

This is his most famous work, Study after Velazquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, from 1953:

You can see that raw emotion expressing itself in the canvas, can’t you? Nearly all of Bacon’s paintings make you feel at least a little bit uneasy. There’s the uncanny valley effect, where things that look mostly (but not quite) like us are very disturbing, and there’s iconoclastic imagery that seems to wrestle with Bacon’s love for the Old Masters.

Oh, there’s one more interesting thing: it seems very likely that this Francis Bacon was named after another chap who lived more than three centuries earlier.

We’ll call this fellow Sir Francis Bacon for clarity’s sake. We have good reason to believe the painter was named after Sir Francis—for one, Francis the painter claimed to be a descendent of the philosopher-scientist who came much earlier, and Francis wasn’t exactly a common Irish name.

There’s also an intriguing connection between Francis and Sir Francis. Both Bacons seemed interested in showing us what was hidden within both the world and within the human mind. While the painter channeled emotion and expressed it vividly through the visual medium, Sir Francis focused on reason and observation to draw conclusions about the world.

Sir Francis Bacon was born in 1561 in London. His family was wealthy and connected, so Sir Francis was able to attend Trinity College in Cambridge, one of the centers at the forefront of intellectual thought in Europe at the time.

It seems very likely that Sir Francis viewed politics as a solid path to power. He openly sought the favor of Queen Elizabeth and James I, serving as a member of Parliament, and even attaining the status of Lord Chancellor. This was somewhat akin to Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, but without being quite so constrained to the judicial branch.

In other words, Sir Francis did, indeed, attain a lot of power, but he was also marred by allegations of corruption. His political career was doomed to failure when he was briefly imprisoned in 1621, and although he was pardoned, Sir Francis never returned to a career of politics.

I can’t help but wonder whether Sir Francis’s firm views contributed to his political downfall. What he brought to the table was the very idea that we could make things better for ourselves by observing the world around us and drawing conclusions, and that included the way things were run. This surely threatened the status quo.

Regardless, it’s fair to say that Sir Francis shook things up, and for centuries to come. I have to stop here for a moment just so that we can really put into context how important his contributions were.

Did Sir Francis Bacon invent the scientific method during the early 17th century? Not precisely, but he certainly shaped it into something that looks like what we use today, and probably more so than any other one person, ever.

All of the modern technology we’re using, including how we feed so many people, how lives are saved and extended, and everything good and bad that goes along with all that owes its existence to the scientific method, and nobody pushed the scientific method further along than Sir Francis.

His insistence upon observation to corroborate theory seems obvious to us today, but the conditions to run controlled experiments weren’t always so easy to attain prior to the industrial revolution, and Aristotle still carried an absurd amount of credibility among scholars.

Instead of divining ideas through pure reason, Sir Francis instead suggested forming and testing a hypothesis, and then—and here’s the key part—actually looking at what happened in order to decide whether the hypothesis might be wrong.

If it disagreed with experiment, it should immediately be thrown out or revised. Bias (“idols”, as Sir Francis called them) should be identified and thrown out. No cherry-picking would be allowed.

Sir Francis sums it up in his Novum Organum, published just one year before his brief imprisonment:

For man, being the servant and interpreter of nature, can do and understand so much and so much only as he has observed in fact or in thought of the course of nature: beyond this he neither knows anything nor can do anything.

Now, I don’t want to oversell Sir Francis’s contributions here. There were plenty of other incremental steps along the way, including polymaths from the Islamic Golden Age like Al Kindi and Ibn al-Haytham (“Alhazen” to western ears). It’s been refined since Sir Francis’s time, too, so the way we do science has been a slow evolutionary journey with hundreds of contributors.

Still, nobody pushed the scientific method as far as Sir Francis, and I’m grateful for what this method of thinking has done for the world so far.

After leaving political life, Sir Francis felt free to pursue his intellectual pursuits with full aplomb. In a way, this mirrors Francis the painter’s painful expulsion from home at age 16. Both Bacons suffered during these experiences, but both were also liberated afterward.

Both Bacons seemed to be interested in the hidden aspects of life, and of challenging convention with boldness, not fear. Both Bacons were scarred by controversy, and both ultimately provoked a lot of interesting conversations.

Both might be connected by family lineage, too!

Amongst people who don't believe William Shakespeare wrote his own stuff (less common than in the past), Bacon is considered one of the leading candidates for the authorship. The much beloved "Peabody's Improbable History" of "Rocky and Bullwinkle" riffed on this amusingly by showing Bacon interfering with a "Romeo and Juliet" production gone wrong. ("Bacon!" "With eggs!" (throws them). "SCTV" did something similar with their later sketch "Shake 'n' Bake".

I have a friend in London who's writing a book on the second Bacon.

As to Bacon the First, as David P pointed out in his comment, he might well be the real Shakespeare (although I tend to favour Marlowe or the Earl of Oxford as more plausible candidates.)