For all of human history, right up until the modern era, all of the great sounds we ever made just kind of vanished into the cosmos.

That’s not entirely right—sound waves didn’t really disappear, but instead, they affected their immediate surroundings and then dissipated into nothing we can trace today. You get what I’m saying, though: all of Shakespeare’s original plays, Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” speech, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address… it’s all either written down, or it doesn’t exist.

And writing as a faithul representation of sounds? Forget about it. Deception is among the very oldest writing we can find, with kings lists of Sumer reaching back to an implausible past, and nearly five thousand years of manipulation since then.

Vinyl records aren’t the first way sound was recorded, but I want to let them have their moment with us here. The way they work is ingenious and really incredible, and I’ll get to that. But when I was eleven or twelve years old, it was all about the physical objects themselves, and what they could do.

I say “objects” because each record normally came with a soft sleeve and a harder outer case, both designed to keep the record safe and in place. There might also be a liner insert like a little booklet with some records, but nearly all had the inner sleeve and outer case.

Sometimes, lyrics would be printed on the inner sleeve itself, like with Billy Joel’s The Bridge right here:

This was a time when the way to get new music was to buy an entire album, at least until mixtapes were dominating my world. Billy Joel was a known quantity for me and my friend Matt, who had introduced me to Joel’s music earlier. I think Matt or his brother had several other Billy Joel records, so it made sense for me to pick this one up.

The idea here was to spend an hour with Billy, reading the lyrics and listening to the record. They even threw in some pics of recording with Ray Charles (I would too, Billy!), so you can get a sense of how the album was made.

My record purchases tracked my musical tastes, too. At first, it was all Billy and the Beatles, with roughly equal measures of each—I was way more obsessed with the Beatles, but I had already bought their tapes before I got my record player.

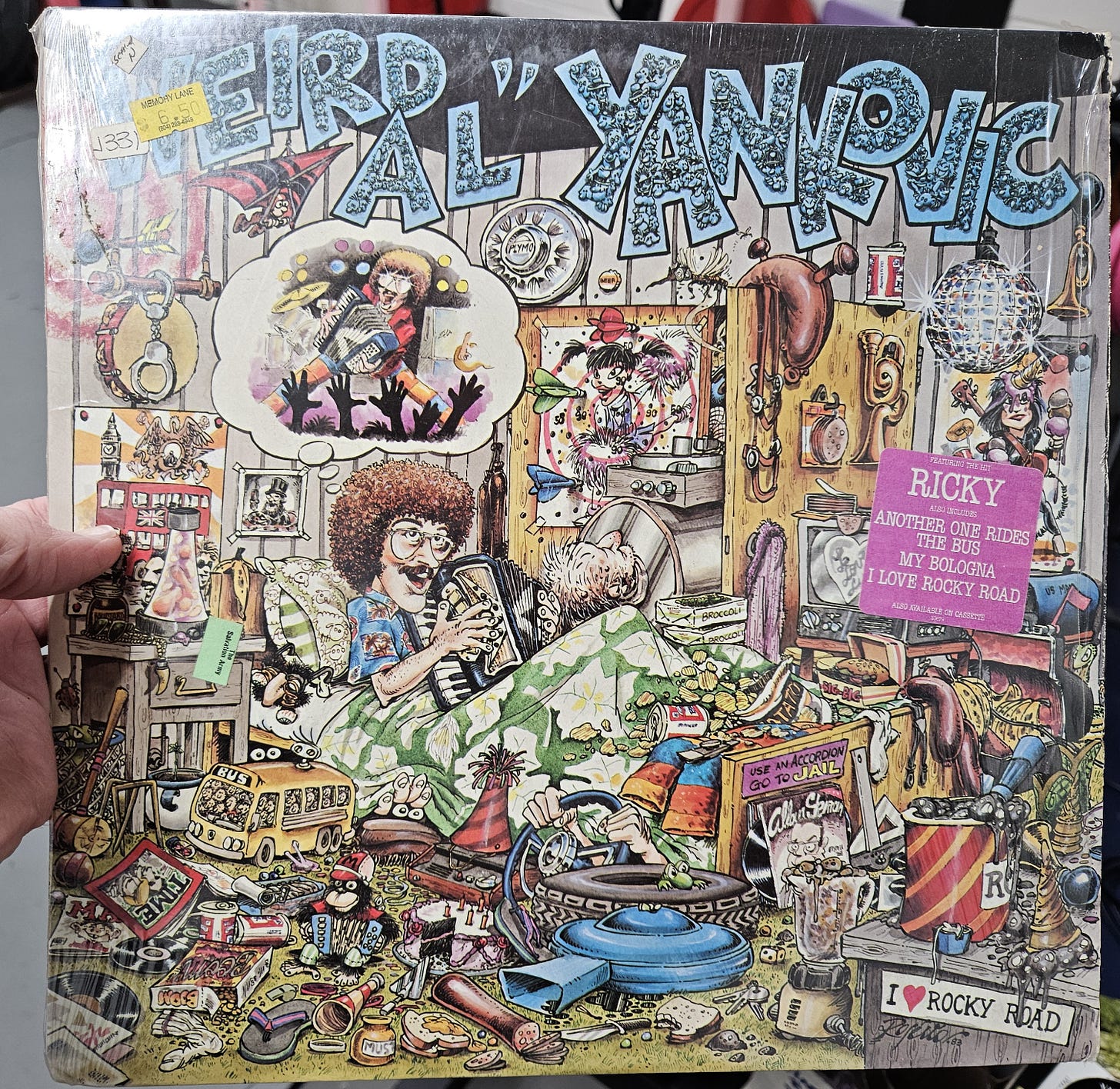

Middle and high school brought me closer to Weird Al, and I eventually found his first record on vinyl at a used record shop. Not bad for $6.50!

Some bands even went further, embracing the idea of a picture disc —they just printed the image right on the record itself, adding to the collectible nature of the records. Thrash was added into my listening routine later on, and I stumbled on this beautiful pressing of Nuclear Assault’s first record:

All right, so what’s happening when a needle fits into the grooves of the record? How does Weird Al’s accordion or Nuclear Assault’s thrashing guitar end up in my eardrum?

Eardrum is an interesting word, and it describes itself pretty well. A sound wave will cause this observing device you have to resonate, and that wave turns into an electrical signal that reaches your brain.

I touched on a key phenomenon in Seeing Sound (feel free to open a new tab for later), where the gist is that you can actually see the way sound waves propagate across a surface, like if you put sand on top of a speaker that’s facing up.

There are some areas of much higher vibration, and you can see the little grains of sand steadily vibrating away from these intense zones. These are called antinodes, places where things don’t like to gather together. Nodes, by contrast, are the quiet, still zones where everyone wants to just hang out and chill.

When a vinyl record is cut (recorded), the sounds from the band cause varying vibrations that you can feel if you stand by speakers that are loud enough (don’t do this too much). These same vibrations cause a very tiny, sharp stylus to vibrate along with the sound.

The stylus, kind of like a tool I once used for etching (printmaking) class, keeps moving along with the sounds coming in as a really, really soft record spins around. It’s not exactly a record, but instead a lacquer disc made of very soft material. If you can imagine a very sharp needle carving lines into butter, you have a pretty good idea.

If it’s a mono record, there’s just one groove of these… wiggles. If it’s stereo, there are two of them, set at a 45 degree angle.

Now, what about playing?

When you pick up the needle to drop it into that first groove, you might notice that it’s kind of heavy. This is due to the cartridge, which operates a bit like your cochlea. It takes these tiny vibrations coming in, and converts them to an electrical signal by way of coils and magnets.

Essentially, it’s the recording process in reverse from here.

I don’t know if Billy Joel’s The Bridge album is a good enough conversational bridge, but let me give it a try here: do you remember any of the songs from this killer album? Are there any records you cherish today?

I think what has changed the most about sound in our lives is that we used to own our music. Now most of us rent the license to play the music. It’s not ours anymore. And that’s the attraction to vinyl, to hold the sound in your hands and possess it without clicking Yes to a huge legal document.

-"They even threw in some pics of recording with Ray Charles (I would too, Billy!)," Ray and Billy famously teamed up for the tune "Baby Grand", which I assume is there.

-In most cases with albums of this era, lyrics, album credits and such would either be printed on the inner gatefold of the album sleeve, or on a separate sheet of paper included with the album. In the CD era, the sleeves or booklets accompanying the disc took over that function.