Collecting comic books as a kid taught me a lot. One of those things was how to value collectible items, and this involved a few notable steps.

First, you would need to look up what the comic was selling for. There was one definitive tool I absolutely had to have for this: the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, which seemed like it had been around forever by the time I started collecting comics around 1985, but it actually only started in 1970.

Once you found the specific title and issue in the price guide, you needed to know the overall condition of the comic book. If it was in very fine or near mint condition, it might be worth $10, but if it was merely fine, you’d expect more like $5, and you might be lucky to get $2 for a very good copy.

I saw that Overstreet provided an anchor of sorts, but the actual sale prices fluctuated quite a bit, depending on how hot the title or issue was at that particular moment. It was intoxicating for me to try to figure out how this all worked. I described what came next for me in The Collector:

I created a notebook to track all my comic books, and meticulously went through Overstreet’s Price Guide to do my best to determine a value for each comic I owned, one at a time. Collecting comic books was already around by the mid-80s, but it grew a ton while I was involved, including the availability of a monthly price guide.

I made it a point to update the notebook every month, whenever those new monthly guides came out. So, in addition to drawing these comics every day, I was also painstakingly pricing them on a regular basis. It might be fair to say I was a little obsessed.

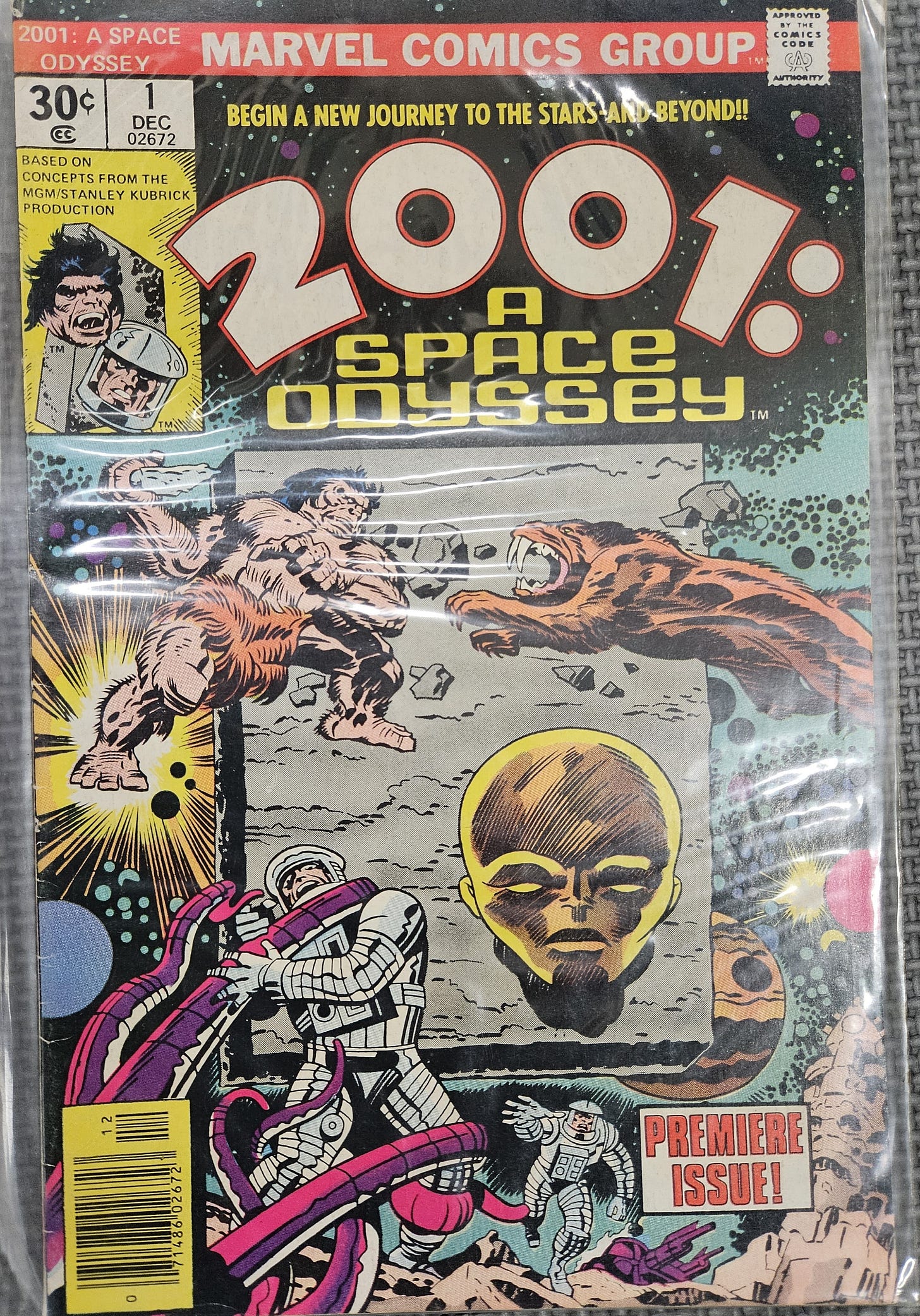

Over time, the patterns became more predictable. I saw what might become a valuable comic one day: an origin story, an introduction to a new character, or the first issue drawn by an exciting new artist. Number one issues were worth keeping an eye out for, like this issue of 2001: A Space Odyssey I found somewhere:

These were tried and true factors in raising the value of a comic book, and over the ensuing three or four years, I got a strong sense of how the game was played.

Then, gimmicks arrived.

These were ways for comic book producers to juice their sales, utterly decoupled from actual value. I’m talking about putting a comic book into a bag so that it stays sealed, so there’s that extra tempting layer just for collectors. Most people will buy a comic book and then read it, but during the late 80s and early 90s, there was a rapidly growing group of consumers who might buy multiple copies of the same issue if they thought it might go up at some point.

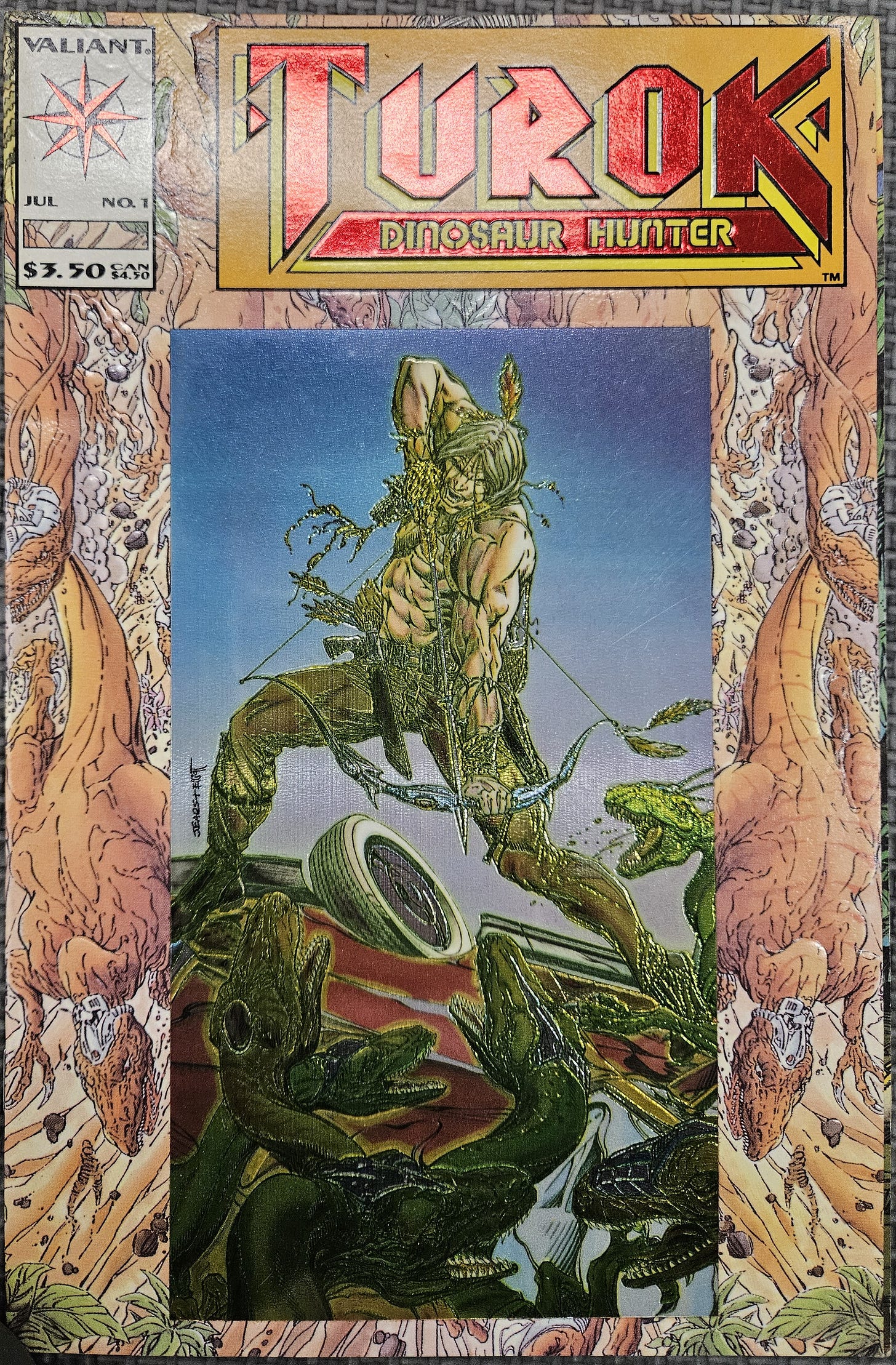

Or, instead of bags, foil covers became all the rage. One brilliant innovator had the idea of embossing a foil cover onto a comic book, and then everyone just copied it once they saw how much more those issues sold. Here’s Turok number 1, one of those examples I somehow ended up with:

Gimmicks really threw a wrench in valuations. Suddenly, the market was flooded with foil-embossed, bagged issues, trading cards inserted into the comics—you name it, all in the name of manipulating collectors into buying these now so that they might one day go up in value.

This is probably the first time I really noticed market manipulation, probably because I was now part of the market.

Gimmicks are everywhere today. They first rose to prominence during the early 20th century in the US, right as Edward Bernays was just beginning to sell “torches of freedom” to women, and modern marketing was born. Suddenly, there was a crowded marketplace of products, and one way to get your product to stand out was to throw in something that grabbed your attention.

It didn’t matter much if the gimmick added actual value, as long as it differentiated your product from those competitors. Over time, guerrilla marketing borrowed from these same tactics, with creative thinking being the true currency to reach eyeballs, not necessarily marketing dollars spent.

Some folks speculate that the word gimmick started out as an anagram for magic, or at least a play on the word. That’s because stage magicians would often have a secret device that made their trick work for the audience. Alternatively, there’s an older word called gimcrack that means a cheap trinket—and while etymology is important to me, this word has murkier origins.

Regardless, the word caught on in the public mind, and by the time I started collecting comics in the 80s, the word (and marketing tactic) were both well understood by most Americans. Now, that’s not to say they didn’t work! If you were selling a product, you still needed to have some way to introduce it to people, and gimmicks were one affordable (and still effective) way to get that sales snowball rolling.

What are some gimmicks you’ve noticed?

Oh goodness the gimmicks. A harder question is where aren't they?

Substack's "Bestseller" badges can be considered gimmicks of sorts.