Grunge

The early 1990s was the perfect time for rebellion. The dominant trends from the 80s were just winding down, and all that excess and greed had culminated in a rapid meltdown of popular musical figures.

There was Vanilla Ice, who was on top of the world with Ice Ice Baby in 1990. By 1991, Third Bass was openly mocking V-Ice in their Pop Goes the Weasel video:

This wasn’t the first diss track—songs where an artist talks about how much another artist sucks—but it was the first on such a prominent scale. It didn’t much matter if you were MC Hammer, Michael Bolton, or Richard Marx—once your time was up, it was up.

That backlash was most brutal against hair metal music. If you think about 80s MTV metal, you think about makeup, teased hair, and tailored “rebellious” clothing to look a very particular way.

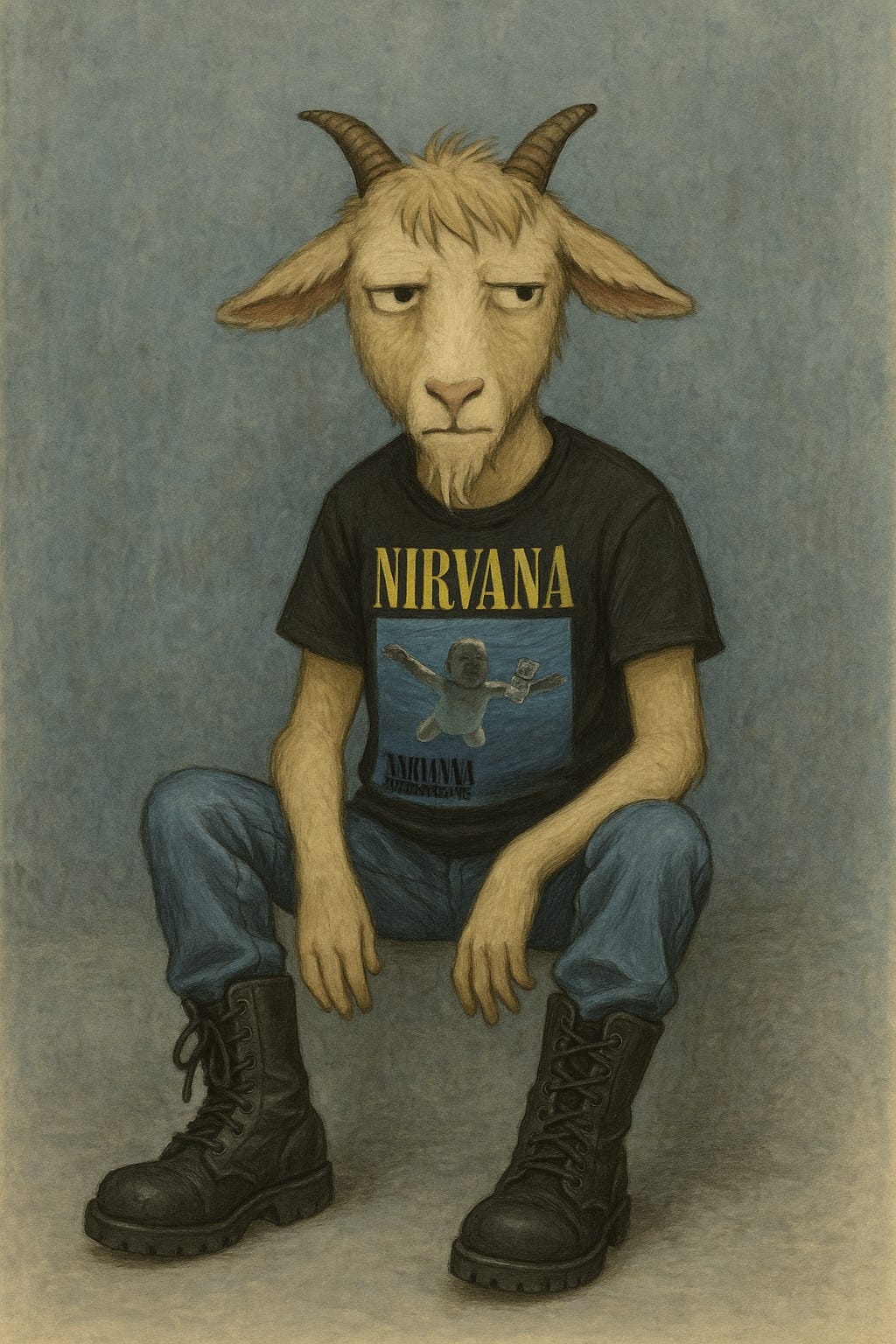

This entire world was ripe for anti-fashion.

This was a similar setup to punk in the late 1970s, which became a rejection of all things mainstream. The difference now was that punk itself involved too much playing dress-up for this generation’s tastes. We wanted something completely different, but without fuss.

On Sunday, September 29th, 1991, Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit premiered on MTV’s 120 Minutes, and I shuddered as I heard and saw what this band represented. For the first time in my life, I heard someone really speaking my language, giving art and voice and music to the fiery core of resistance and agency living inside of me.

This dressed-down movement really appealed to me. After learning to loathe preppy fashion, combat boots and lazy flannel seemed pretty much spot-on, although I never really took to flannel.

Grunge wasn’t just about fashion, though. The lyrics and music attempted to tell a story without flash and glamor—the opposite of 80s hair metal. These weren’t stories about partying and “getting laid” as much as they were harrowing tales of not quite fitting in.

By the time I heard Nirvana in 1991, the sound that would be called grunge had already been percolating for a few years. Sub Pop records, the label that eventually carried Nirvana’s Bleach, was founded in 1986 in Seattle. Short for Suburban Pop, this zine-turned-label would create a scene in Seattle, just like there had been a Motown scene for soul music during the 60s.

You started hearing about “the Seattle sound” before you started hearing about grunge, at least where I was. Suddenly, there were other bands with a similar sound becoming prominent on the national stage. Soundgarden, one of Sub Pop’s first signed bands, broke out around the same time as Pearl Jam, another Seattle band. Alice in Chains had also attained consistent radio play with Man in the Box, which was nominated for best hard rock music video of the year on MTV for 1991.

This wasn’t really a sound, though. These bands were all different, and there were other bands from outside of Seattle with a similar aesthetic, so a new buzzword began to appear in my vocabulary: alternative music.

The word alternative did an awful lot of heavy lifting during the early 90s. This included any genre that wasn’t mainstream, but most people meant that edgy blend of punk, metal, and hard rock that kids had begun to think of as grunge. Grunge eventually won the vocabulary war here, but alternative proved useful if you were talking about REM or MC 900 Ft Jesus, or another band that clearly wasn’t hard rock.

Grunge was useful to me for about a year, and then punk just took over. It was an excellent gateway drug to rebellion, but it didn’t go nearly far enough for me. Here’s how I described my mindset heading into 1993:

Grunge was often classified as alternative music, but by 1993, everyone was wondering the same thing: alternative to what? In other words, the bands that were countercultural were now simply mainstream. Meanwhile, my own ethos was pointing me in the exact opposite direction. For this reason, I very nearly missed my Lollapalooza window.

I went, though, and I had a blast!

I can’t tell you how glad I am that I gave myself permission to dance to the likes of Alice in Chains, Primus, Arrested Development, and Fishbone.

Of course, even anti-fashion and rebellion eventually becomes a commodity, and that’s exactly what happened with grunge. Kurt Cobain’s death by suicide in 1994 wasn’t quite the nail in the coffin, but it probably marked the beginning of the end of the movement. Record labels and producers were already trying to make records more grungy, influencing the sound and look of artists to chase a popular ethos.

RIP, grunge! I really enjoy listening to a lot of these groups today, blending the right hit of nostalgia with legit songwriting genius. Post-grunge, by contrast, is a different story. Here’s where the motivation to make money was a primary motivating factor in the creation process. If you’re a fan of bands like Nickelback and Creed, maybe you can explain why I shouldn’t loathe those bands.

If you’re a fan of grunge, tell me when you first heard the genre, and what drew you in!

And, finally—if you’re looking for more personal tales about music, or just deep dives, I want to recommend three authors I’ve gotten to know here on Substack just a bit. All three do their due diligence and put a lot of energy into writing about music, and each has their own direction.

runs , runs , and publishes . All of them are in this same ecosystem, and if music is important to, I recommend checking them out.

What's interesting to me is how much of the rebellion took place in the US vs. other nations at the times. Almost like it's baked into our core. Then again, we were settled by the disaffected, willing to pick up and leave their nations to some place new and start over.

GenZ pirate hobos are grunge redux