Iconoclasm is a cool word!

It comes from ancient Greek, where the word icon (εἰκών) meant something like “portrait” or “image”, and the second part of the word (κλᾰ́ω) meant “to destroy.”

Over time, we’ve seen a lot of this destruction of images. You might know the phrase because of its use during Byzantine times, but the idea goes back a long time.

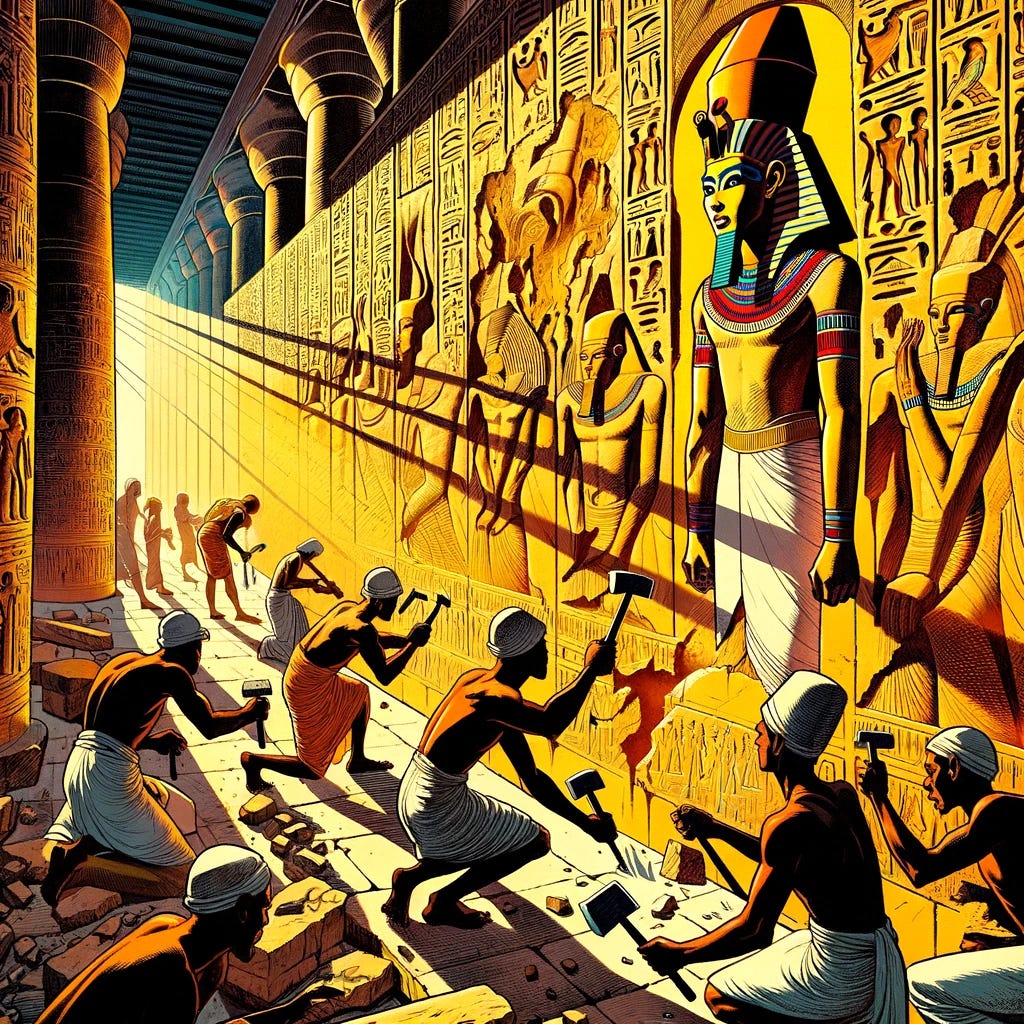

In ancient Egypt, after a thousand years of a well-established pantheon worshipped by millions of Egyptians, Akhenaten—the new Pharaoh—decided to consolidate power by creating a brand new religion. The god Aten would be at the center of all worship from now on, and in fact, all other worship was prohibited.

Egypt wasn’t quite forced into monotheism, but it might be fair to say this culture was now monolatrous—worship of the top god was encouraged, but others were permitted. Akhenaten ordered every reference to Amun, the chief god of the existing pantheon, to be chiseled away, but no gods were safe from erasure. Artwork and monuments were destroyed, and countless artifacts were lost. Only images of Aten would be allowed from now on.

Likewise, the Byzantine Empire (also sometimes thought of as the Eastern Roman Empire) saw a period of iconoclastic fever—in fact, there were two distinct fevers separated by a bit of a pause for breath.

By the time of the 8th century, icons were prominent in the Byzantine church. Paintings and images of saints (or of Jesus, or of the Virgin Mary) were central to Christian worship, with many believing the images themselves had miraculous powers.

This caused the ire of a growing opposition, who reminded the constituents of the Church of the Second Commandment in the Bible, where idol-worship was explicitly forbidden. Meanwhile, the Islamic Caliphate had risen up at unimaginable speed, taking over the Mediterranean in the span of a few decades. Fear of this rival religious empire caused conservatives in the Church to double down on purity, and the icon-smashing began.

These are classic examples of the destructive nature of iconoclasm, where an idea becomes the enemy so intensely that physical destruction of the very images themselves is required. There’s a different type of iconoclasm, though, that doesn’t need to involve physical destruction.

In this type of iconoclasm, you don’t even try to erase the image from people’s minds, although that’s certainly the approach employed by governments with a more authoritarian bent. No, instead of rewriting history, the idea is to shatter the respect an image instills in people.

This is my kind of iconoclasm! There are some ideas that have made us afraid to act rationally, like vestiges of an older time. As a teenager, these were illusions I was eager to shatter.

If everyone was supposed to dress a certain way for a particular social function, I was there to push back against that notion, and so was punk rock. Similarly, if it was considered impolite to speak out against the government, UK punks were shouting and spitting. They were offending, above all else.

Offense was the point, although it worked best (in my opinion) whenever it was directed toward those in power, and this was nowhere more prevalent in the world of icons. The Pledge of Allegiance was one of those icons, and I felt as though I had to burst that iconic bubble personally:

The Pledge

I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, everyone else began every morning. I was sometimes forced to stand up, but I never gave in to actually saying the pledge out loud myself, even though I knew it by heart, just like every other kid attending public school in South Carolina during the late 80s.

Have you personally destroyed any icons in your own life, metaphorical or physical? Did it help you to move on past an older way of thinking, or was there some other reason behind the iconoclasm?

On the one hand, we shouldn't needlessly destroy our traditions and culture

On the other hand, we should always inspect our traditions and cultures and remove the vestiges that are no longer helpful. Sacred cows make the best burgers.

I'm well acquainted with this concept, but more for its metaphorical meaning of destroying existing standards in cultures and art forms, rather than physical destruction of objects.

I have considered myself to be fortunate to have been a witnessing viewer of the revolution in television animation during the 1990s and 2000s. Iconoclasm was the order of the day in the programs of that time; it had been forcibly suppressed for a long before that time, but the entrance of a new generation of animators with new standards changed things.

Then we have the Internet-enabled class of "disrupters" that have dominated the 21st century. "Move fast and break things" could easily be a definition of iconoclasm.

Physical iconoclasm doesn't have too many counterparts after the ancient period, with Savonarola's Bonfire of the Vanities in Venice being one of the more obvious examples. In America, it has occurred with the mass immolation of comic books in the 1950s, the burning of Beatles items as a backlash to John Lennon saying the group was "bigger than Jesus" in the 1960s, and other such "panics".