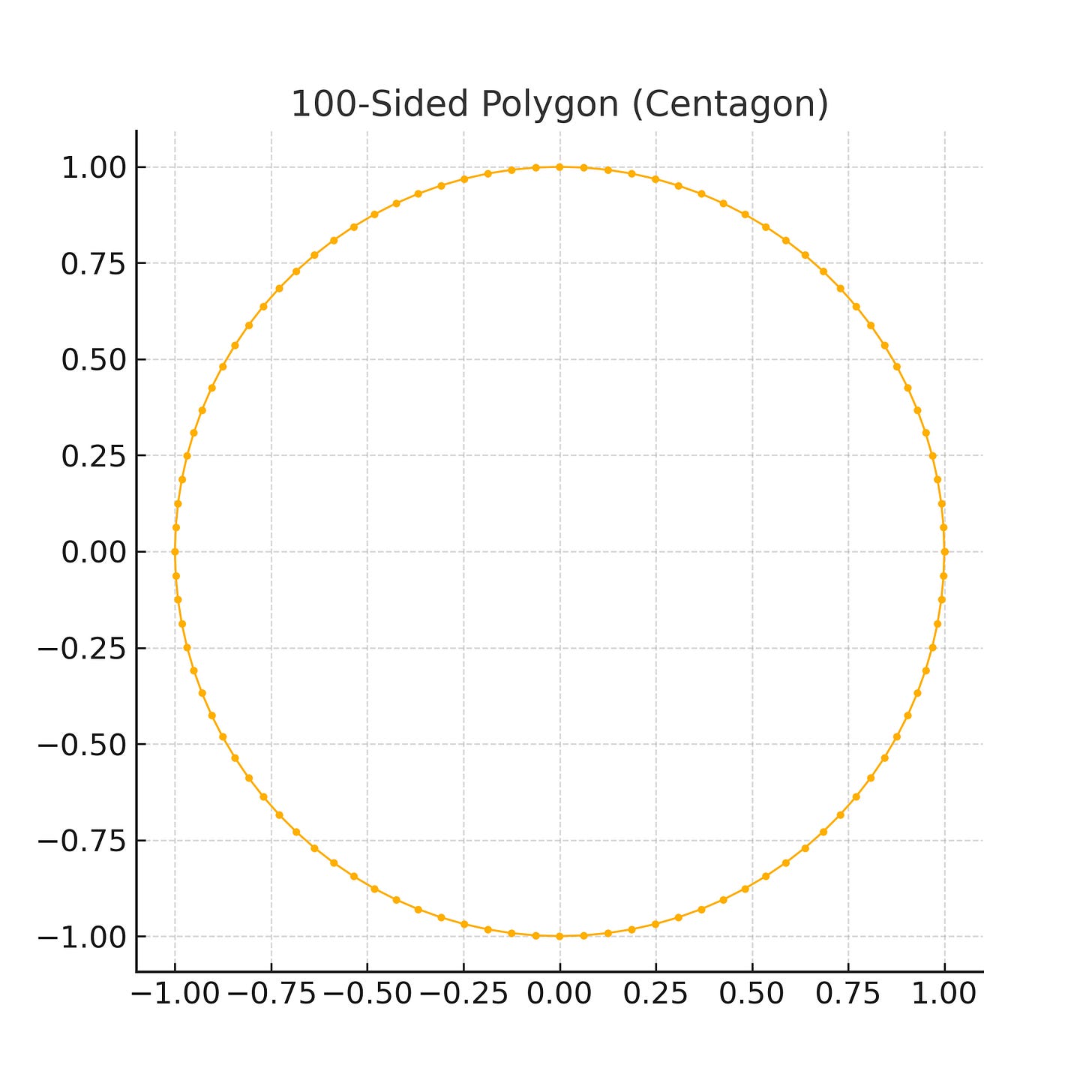

Imagine trying to draw a circle, but with only straight lines. You can make an octagon with just eight lines, and you know that if you add a few more lines, the shape will start to look more like a circle.

If you had a hundred of these lines, you might not be able to tell the shape isn’t a circle any more. It’s still a shape with straight lines, but it seems more circle-like to you now. You might say that the shape is approaching a circle as you add more lines.

What if you just kept adding lines? If you hit a million lines, you’d still have something approaching a circle, but no circle.

This is exactly the problem that Newton was trying to solve when he ultimately invented calculus. Meanwhile, his colleague and nemesis, Leibniz, came up with a solution around the same time, independently of Newton, and from a totally different approach. He was thinking about Zeno’s paradox, and how you can always divide any remaining distance by half.

According to Zeno, every time Achilles reaches the point where the tortoise was, the tortoise has moved a little bit further ahead. For Achilles to reach the new position of the tortoise, he has to cover this new, albeit smaller, distance.

Again, by the time he does, the tortoise advances just a little more. Zeno argues that this process will continue infinitely, implying that Achilles will never be able to overtake the tortoise.

Both great thinkers ultimately realized that they needed to invent a concept that other people could use to solve this problem every time in the future. What was needed was a way to add things up so that they never reached a number, no matter how many of them you added up.

For Leibniz, there needed to be a way to have an infinite series of numbers that added up to one. For Newton, he needed ever more straight lines to make up his circle.

They invented infinitesimals.

Infinitesimals are so, so useful. Immediately, Newton applied this concept to what became the great work of his life, his law of universal gravitation. In an incredible moment, the celestial bodies were linked to earthly gravity.

Think about how much of nature is all about spheres and curves. A particle shoots out gravity or electromagnetic force equally in all directions, so the overall wave travels in a spherical pattern. This new tool allowed us to create entire new fields of study within physics and mathematics.

Engineering, too, took a great leap upward thanks to infinitesimals. Anything fancy and big almost certainly owes its existence to this clever invention.

I’m not here to tell you the whole story of how math came to be. This is more about how one concept proved so useful—just the idea of having something approaching zero, but never quite getting there. This polite fiction has become an incredible mathematical superpower, helping us to unlock the keys to the universe.

Did you take calculus in school? Do you remember understanding the concept of infinitesimals when you took the course? I’m not sure I really got it, even though I was good at getting the answers. What about you?

So this reminds me of something that has always intrigued me. Historically in the USA and much of Asia, video was always presented at 29.97 frames per second... or you could say "sides" of a visual moment. Film and most video in other parts of the world was always presented at 24 frames per second because it gave a more artistic look (often described as"cinematic") though broadcast format capabilities had something to do with it (NTSC vs PAL). But that has shifted over time as things went from analog to digital and most entertainment anywhere in the world is now presented at 24 fps. but formatted for 60p (it gets super techy but it's kind of a side point in what I'm getting at). Except sports and news, which are now often presented at approximately 60 fps. And surveillance camera footage. Objectively, 60 fps is the most accurate to how humans perceive motion, but our brain appreciates the feel of 24 fps more on an enjoyment level. And most, except me, think 60 fps is great for sports and news. I almost always prefer the more cinematic look in about anything I watch, except maybe security camera footage. But I'm weird. Or maybe I'm not, but this is how video is presented much like your circle example if you were to compare "uncircles" made of 24, 29.97, and 60 sides. I don't really have a question, but I think this "less is more for the brain's perception" idea is really interesting.

Upon seeing the word "100-sided Polygon," thousands of D&D fans cried out in unison, imagining in horror what the die version of that would look like.

I used to be pretty good at math in school / high-school, although I opted to take mid-level math during my International Baccalaureat to instead take high level Economics and Physics, from what I remember.