Let’s travel back in time to the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

Just before the American Revolution, things were starting to get interesting in industry, as trends that had held for centuries were beginning to be disrupted.

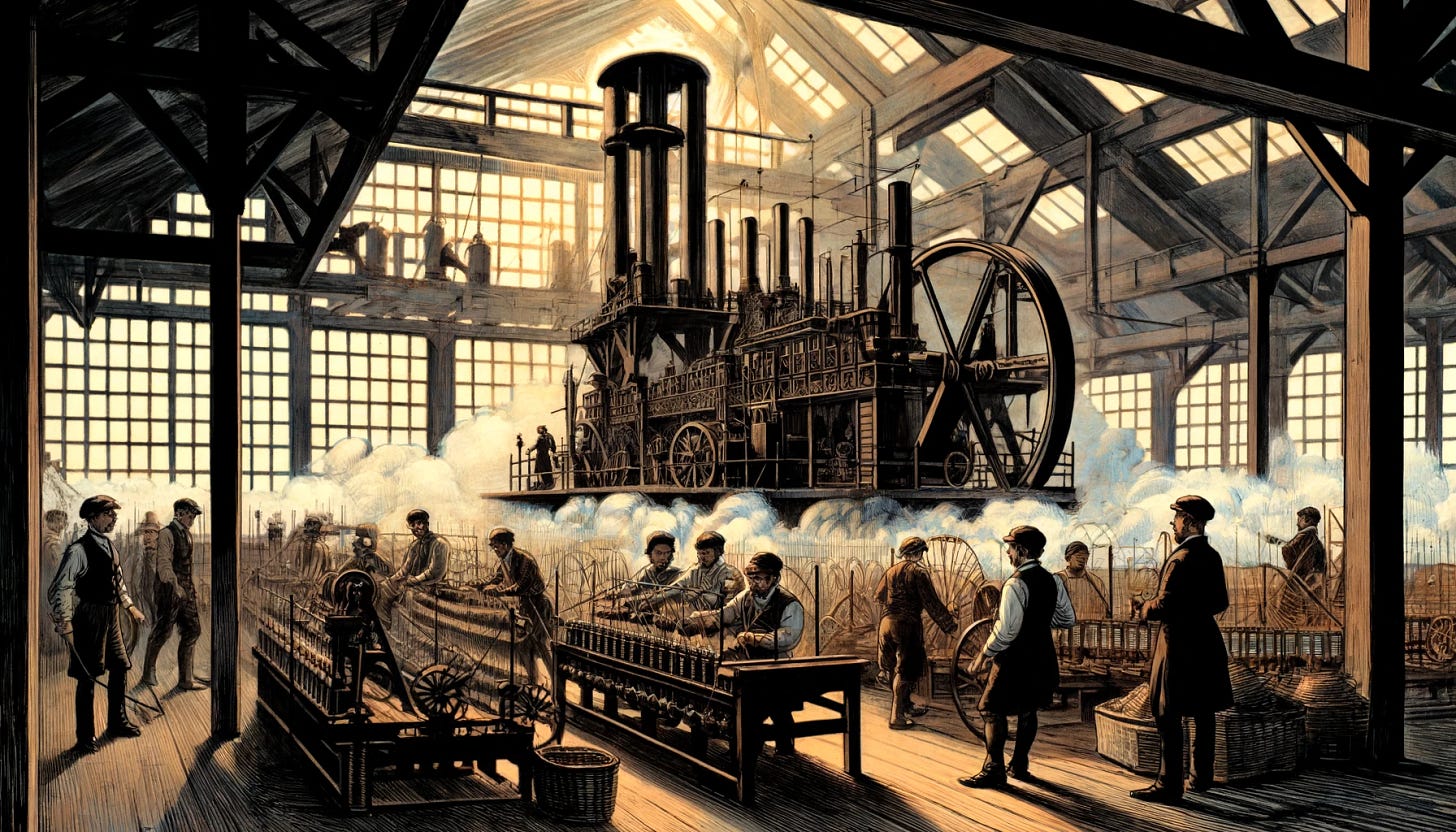

Prior to the 1760s, pretty much all manual labor in Britain was done by hand. There was a little bit of use of wind and water power, but it was extremely limited in the types of tasks you could do with this power, like directly having running water turn a wheel that then smashed grains to bits.

By the end of this decade, there were several notable innovations in the works, including James Watt’s working steam engine (patented in 1769), and the spinning jenny for spinning wool or cotton. These trends continued as Britain began to diverge from the rest of the world.

Technology began to power colonialism, and vice versa—resources could be found anywhere in the British Empire, then brought to any other area of the vast empire with unprecedented speed due to faster ships, for just one example. It was like make-it, take-it basketball: the winner just kept the ball the whole time.

This virtuous cycle pushed Britain through notable phases of innovation, beginning with that very early coal-powered phase, where relatively simple machines could be made to do things no humans could do. Factories and early mass production were made possible by better technology and more power, especially in the textile business, where our old friend the Jacquard Loom enters the arena at the start of the 19th century.

By the middle of the 19th century, steam power was pushing huge trains around on railroad tracks. The first ships powered by steam helped to extend Britain’s lead over the rest of the world in the centuries-long race to exploit the world’s human and physical capital.

The telegraph’s invention meant that communication that took days or weeks now took seconds.

Steam and the telegraph gradually gave way to electricity and the telephone. The invention of the internal combustion engine paved the way for a new transportation paradigm, too: the automobile. Land vehicles that could move faster than horses could now go places where there weren’t railroad tracks.

This takes us firmly into the 20th century, where electronics and computers have revolutionized communication and information processing over the last hundred years or so. Today, people have moved on from landline-based telephones to mobile smartphones. We’re looking at autonomous vehicles and drones at the edge now, with generative AI suddenly available for free to anyone with an internet connection.

Britain marched through all of these distinct phases of revolutionizing their industry, and the United States (more or less) followed this formula. So did Europe.

This became a playbook the developed world understood well, and they sought to help other nations develop by using this strategy. Britain, the US, and Europe had followed particular paradigms of development, from steam to coal to oil and beyond. They had gone from horses to the telegraph to the landline to the mobile device, and so could other nations, or so the reasoning went.

However, the developing nations of the 20th and 21st centuries have had one thing Britain did not have, and that is the ability to study these cycles of innovation and gradual improvements for a very, very long time.

Leapfrogging, the practice of skipping a generation (or two) of technology, is nowhere more clear than across African continent. Fellow Substack writer

talks about how mobile devices are providing banking services for the first time in Kenya.Meanwhile in Nigeria,

is currently leveraging AI technology to create a tool that can automate and speed up diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized treatment plans for cancer patients. “We plan to position it to serve the African market first but if we see a need outside Sub-Saharan Africa then we will scale it out,” Edem says.Leapfrogging isn’t contained to the continent of Africa by any means, either. In Bangladesh, Mobile Financial Services have enabled people to perform transactions, access credit, and save money through their mobile phones. Meanwhile in Peru, where healthcare infrastructure is underdeveloped, healthcare providers can reach patients in remote areas and diagnose people remotely with live video chats (which shows that many Peruvians have leapfrogged traditional means of communication).

Skipping straight from not having access to a landline to using a mobile device can have some profound effects. There’s little time to adjust to an incredible new paradigm, so you sort of miss out on the stair-step way technologies usually develop. This causes lots of disruptions and inequality, but on the flip side, it can allow an entire nation to modernize much, much faster.

Globalization has made all of this possible. If tech is invented here, it’ll be over there before very long. The mobile revolution was especially significant because it allowed everyone to understand what was happening in the world, so any sort of innovations today make their way around the world quickly.

Developing nations see that there are better solutions to the blueprint Britain created and the West followed. Much credence is often given to first-mover advantages, but waiting until later in the game can have some advantages, too.

I’ve barely scratched the surface with leapfrogging today, but that’s all I really wanted to do for now. Understanding that this is happening all over the world can help us see things from another point of view, so I hope this gives you something to think about.

What are some good examples of leapfrogging you know about? You get bonus points if it’s something happening in your region, but everyone is welcome to help me think about this today.

I don’t know. I was last there in 2015 although I keep in contact with friends and colleagues there. I doubt it. That said, in the late 90s I had a solar panel to heat water and in the villages some used solar stoves. Certainly many houses in Kathmandu have solar panels and batteries. Outside the cities I am less sure.

Nepal leapfrogged in the 90's with telephones. Instead of landlines (a real problem in the mountains with few roads), everyone got mobiles...