Menus, Meals, Matrix

Ever hear the phrase “the map is not the territory”?

This is solid advice to remember, even though it certainly states the obvious. If you’re staring at your phone’s screen, watching a little icon representing you riding around on whatever road you’re on, you’re probably well aware that nothing happens to you when you move the little icon around.

The map manipulation metaphor is a very obvious way to represent this idea, but it gives the wrong impression. Instead, the maps we use can be incredibly subtle, and we sometimes don’t even notice that we’re using them instead of navigating through reality.

One of the first thinkers to articulate this was Plato, who wrote about a cave where prisoners saw only shadows dancing on the walls, manipulated by humans with little shapes they made against the flames. When one prisoner escapes and returns to tell the others about the exciting reality out there, the other prisoners think he has gone crazy:

Reality’s New Clothes

The prisoners stared intently at the dark, two-dimensional forms playing out a drama for them to observe.

Plato’s allegory made a great impression on ancient thinkers, and the idea has been reiterated countless times since then. Sometimes scholars would pick up on Plato’s ideas and build on them, but just as often, the idea would crop up independently.

Shortly after the time of Plato, but far away, Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi had a dream of being a butterfly. When he woke up, he said that he didn’t know if he was a man who had dreamed of being a butterfly, or if he was a butterfly dreaming of being a man.

The Hindu concept of maya may be even older, with actual underlying reality being obscured by the world we can see, hear, and taste with our senses.

Centuries later, Rene Descartes picked up this concept and ran with it. At this time, people were just beginning to be able to test the limits of human senses, and there was a new framework of scientific thought slowly developing.

This new way of looking at the human mind separated perception from cognition, suggesting that the world we perceive might possibly be out of whack, even as we carefully contemplate it. The fundamental problem is that everything we learn about the outside world comes in through our senses.

Descartes’s new concept insisted on radical skepticism. This meant that you had to try to prove everything, and nothing would be taken for granted. In fact, Descartes went much further than this, insisting that you should try hard to disprove any ideas you have.

This idea is central to the scientific method, and it strikes me as one of the most important ideas we humans have ever come up with.

Over the millennia, we’ve had a lot of great thinkers and artists try to come up with different ways to express this same idea, that reality is deeply different than what our senses perceive. Quantum mechanics seems to justify every bit of mental energy spent on building these analogies—literally nobody can understand this stuff at a fundamental level.

One excellent recent metaphor is The Matrix, easily one of the best sci-fi films of my lifetime. I guess that’s just, like, my opinion, but an awful lot of folks agree with me. If you disagree, let me know why in the comments!

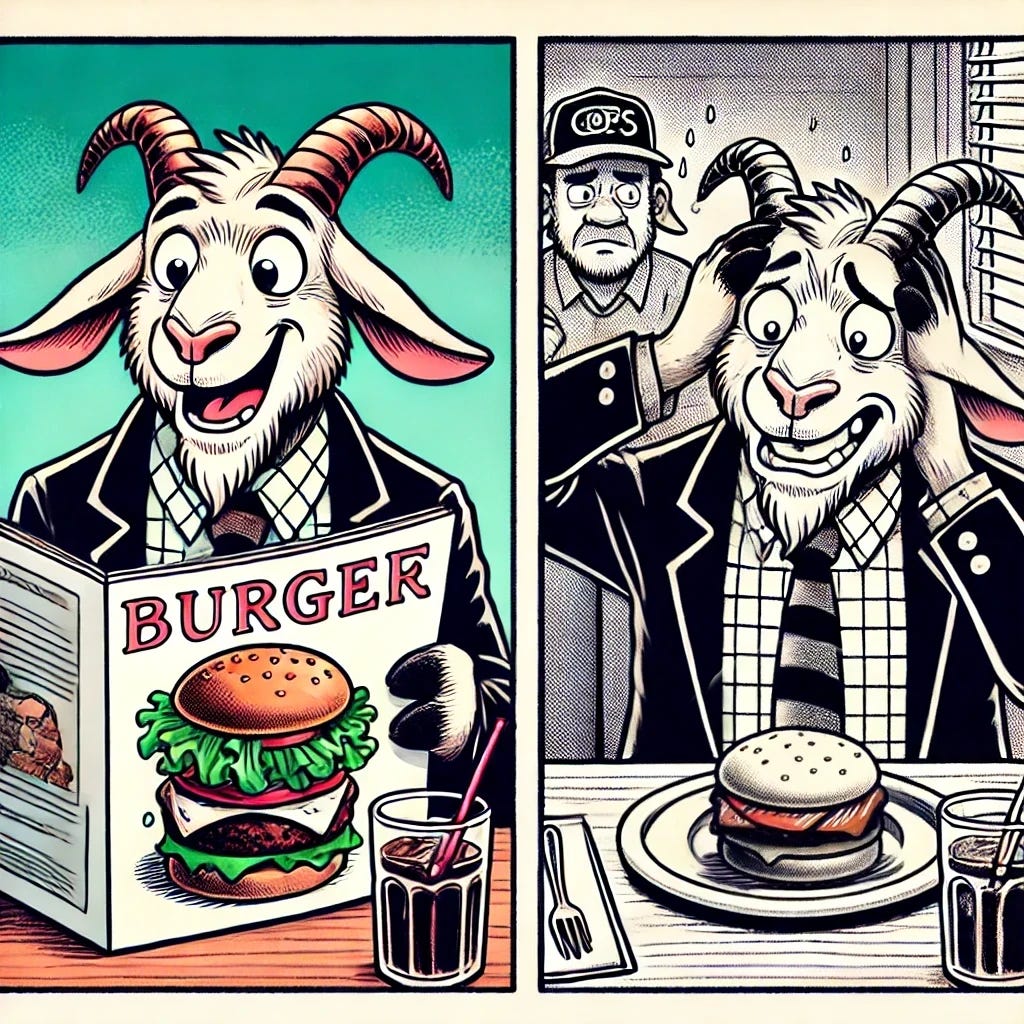

These are all very good analogies, but the title of today’s piece gives away the one I want to use. Ever go to eat in a restaurant and order something based on a picture on a menu? This might be more common with ordering online these days, but the idea is the same.

Fast food restaurants during the 80s were infamous for doing this. They would sell you the juiciest, most delicious looking burger in the world, and you’d get something like a thin version of a hockey puck on a mushy bun.

A British philosopher named Alan Watts wasn’t thinking of McDonalds when he coined the phrase, but he had almost certainly been a victim of disappointment with menus. Watts was deeply interested in Zen Buddhism, and he did a great deal to share Eastern philosophical ideas with academia in the West.

Watts’s enthusiasm led him to use a lot of different ways to describe his ideas, and during a lecture challenging the fidelity of our senses, he first used “the menu is not the meal” on an audience. This analogy proved useful, and it has stayed alive ever since.

There’s one other way to express this idea, and it involves not only limitations about our perceptions of physical reality, but the way we perceive the world differently from one another. Each of us views the world through our own lens, and I had a good time expressing this concept with

in this piece we worked on together:Lenses

You might have noticed that I’ve been doing an awful lot of introspective thinking and writing lately.

Regardless of the analogy you want to use, it’s a good idea to keep in mind that there is always going to be a lens, or a map, or a menu. You’re not really, truly seeing reality for what it is.

That being the case, it really pays to keep in mind that the menu is not the meal.

The blurb/review is not the book… I’m mean, how many book blurbs have you read only to read the actual 60-120k+ book to realize it didn’t live up to the blurb. It’s not always the case, but enough of the times it makes me worried about how I’ve selected to distill my novel down for potential readers.

Also, book reviews. I know the reviewer is giving opinions through their own unique lens. I do it too, when I write a review. I try to give a “shit sandwich” that doesn’t focus too heavily on my unique lens.

AND it is a wonderful tool as a writer to remember when crafting a story because a character’s limited POV and “rose colored glasses”/“blinders” can create tension (and miss direction).

Great post, Andrew!

Speaking of lenses, I believe it was also Daniel Nest who famously said, "The Lens Is Not The Eye." He was ahead of his time.