Move 37

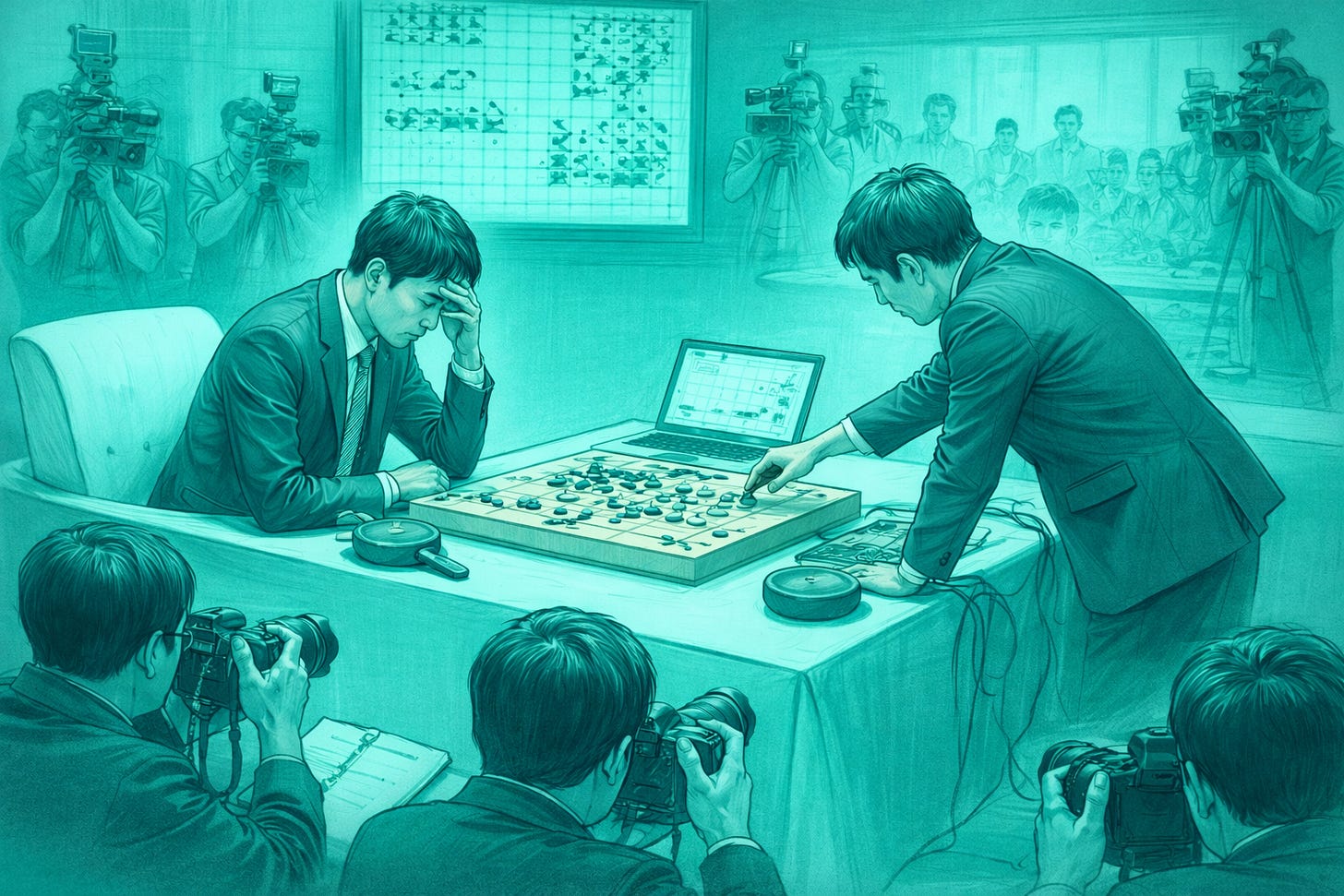

Something funny happened at the Four Seasons Hotel on March 10th, 2016.

The conference room had been transformed into an international competition arena of sorts. Millions of people tuned in around the world to watch the five-game match between multiple-time world champion Lee Sedol, widely regarded as one of the best players of all time, and AlphaGo—the machine designed to beat him.

I mean, it wasn’t designed to beat him specifically any more than Deep Blue had been designed to beat only Gary Kasparov back in 1997, but you get the idea.

Sedol was a great representative for Team Humanity. His intuitive, creative style of game play seemed like the ideal match for a (presumably) brute-force competitor with a vast and deep mathematical ability to test moves, but with no human creativity to draw from.

This was John Henry against the steam-powered drilling machine that ultimately killed him. This was Kasparov taking on IBM all over again. This was man against machine.

Brute force was what the audience expected to see. What I mean is that everyone pretty much expected AlphaGo, created by Google’s DeepMind team, to draw upon human matches and to make predictable but highly intelligent moves.

Move 37 changed everything.

You might not have played Go before, so it’s worth a minute to provide a little context first. While Kasparov’s loss to Deep Blue was incredibly noteworthy—I certainly paid close attention to it—it was considerably more complicated to face off against one of the best players of Go in the world.

It’s like this: chess is to checkers as Go is to chess. It’s not that chess doesn’t involve a great deal of intuitive thinking itself; it’s more that Go resists being reduced to predictable, tactical steps from the beginning. In other words, you’ve seen all the sensible first 2 or 3 chess moves by the time you’ve played for a few years, whereas Go offers way too many possibilities early on.

That’s a big reason why everyone tuned in to watch this contest. Everyone knew machine learning and computers had improved vastly since Deep Blue, but this was a qualitatively different test that would require unexpected creativity from… from a machine? It just seemed silly.

Then, on the 37th move of the second game, AlphaGo made a bonkers move. Instead of clustering its pieces together, the 19th black piece was placed way off to the side in a shoulder hit, a term of art in Go.

The commentators exchanged a few observations. That’s a very strange move, one says. I thought it was a mistake, another chimes in after a considerable pause.

Speaking of pauses, Sedol needed one after this shock. He left the room and returned 15 minutes later to make move 38.

Nobody knew this at the time, but AlphaGo fully understood how weird this move was, but made it anyway. This wasn’t brute force or calculating harder; this was AlphaGo deciding that something humans would dismiss was worth considering.

This changed everything with the way people saw AI, at least in some circles. Suddenly, creativity wasn’t something only humans could do—or was it? Was this just brute force anyway? After all, AlphaGo had the bandwidth to consider those early crazy possibilities, while we humans do not.

This debate continues as AI does all kinds of things that would have been considered the exclusive realm of human creativity, at least up until recently.

Rumor has it that modern AI moved on from Move 37 to Rule 34.