I’m listening to David Attenborough explore evolutionary biology in magnificent detail. His descriptions are magical, but one phrase catches my ear and stays in there for the rest of the day: non-human animals.

What an interesting classification! After all, we don’t go around describing non-wombat animals in similar terms, or non-jellyfish animals, for that matter. To be honest, I wouldn’t complain if we started using non-tardigrade animals, although it seems pretty incongruous and arbitrary (until you learn about those little water-bears).

We humans have always tried to define our place in the world. We’ve been looking out there and modifying our view for countless millennia now, and we’ve been comparing ourselves to other animals for the entire time.

We still do this today. Sure, Usain Bolt is fast, you think, but a cheetah can run twice as fast. Even the weakest gorillas are stronger than the strongest humans. And birds? Forget about it! We can’t come close to flying with our own bodies, but birds sure can.

There’s still something special about us, though, isn’t there?

While we’re not faster than a cheetah or stronger than a gorilla, we certainly have our own superpowers. Namely, we are great at remembering things beyond one generation. That sounds like a pretty lame superpower as compared to, say, Wolverine’s regenerative healing, but it turns out to be our secret sauce.

Today, the line between animals and humans doesn’t actually exist. Instead, humans are a subset of animals; hence the need for the clunky phrase non-human animals. This wasn’t always the case, though.

Depending on where and when you look, you can find examples of human cultures who were certain we should be classified among animals, and examples of cultures where the exact opposite is true.

Native American cultures often viewed humans as a part of nature, living in a system of sorts that we needed to treat well. Likewise, Aboriginal Australian views centered around interconnectedness with other animals, including stories of humans transforming into animals and vice versa.

Meanwhile, belief in reincarnation in South Asian cultures encouraged kindness toward animal forms. You can see echoes of this tradition in both Buddhism and Jainism, where even an insect’s life should be preserved if at all possible. Likewise, indigenous Sub-Saharan African traditions often viewed human and animal spirits as intertwined and often fluid.

Everywhere there was hunting, people were understandably very close to nature, and animals and humans were perceived as similar. Contrast this with Greek philosophers like Aristotle suggesting that humans were at the top of some kind of hierarchy, with only the gods above us.

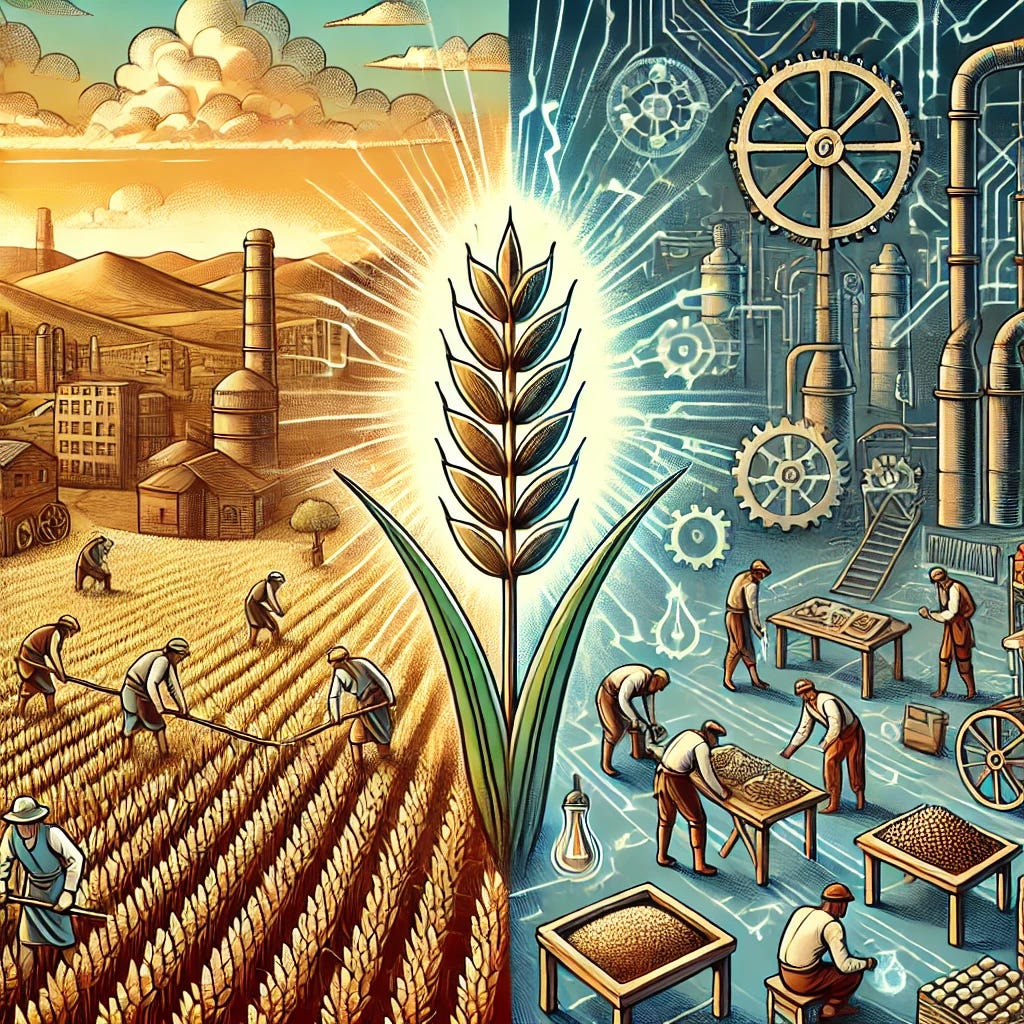

Agriculture and civilization meant that not everyone had to be a hunter or gatherer. Some specialization allowed for a more robust society where inventions could become more common, and a virtuous cycle of innovation occurred in a lot of our earliest cities.

Before we knew it, these settled agricultural societies became the dominant global paradigm. Tribal nomads who relied on the movement of herds of animals to stay alive weren’t able to stay in one place, so they constantly shed tribe members who weren’t able to travel with them. Similarly, they weren’t able to specialize, so writing and reading wasn’t highly prioritized when it took hold in other cultures.

The superpower of writing down ideas so they could be passed to future generations, so you only had to invent something once, gave these city-dwellers a ridiculous competitive advantage in spreading ideas. Naturally, this idea that humans were superior to other animals (or not animals at all) came to dominate the minds of much of the world.

That’s why it was so shocking for the so-called west to discover that we are, in fact, all animals.

If there’s any kind of ironic takeaway today, it is this:

The very thing that separates humans from those other non-human animals—-writing and remembering things beyond a generation, for no other animal has ever been observed doing that—spread the idea that we should think of ourselves as separate from other animals.

Yes, it seems it is those same things that create division and conflict between ourselves and the others that inhabit our planet

Humans don't like being reminded they're not the alpha-omega. :)