Oh great. My hand is falling asleep again.

That’s my thought with virtually every visit to the dentist, the one place where my hand will reliably go to sleep. It’s not really sleeping, though, is it?

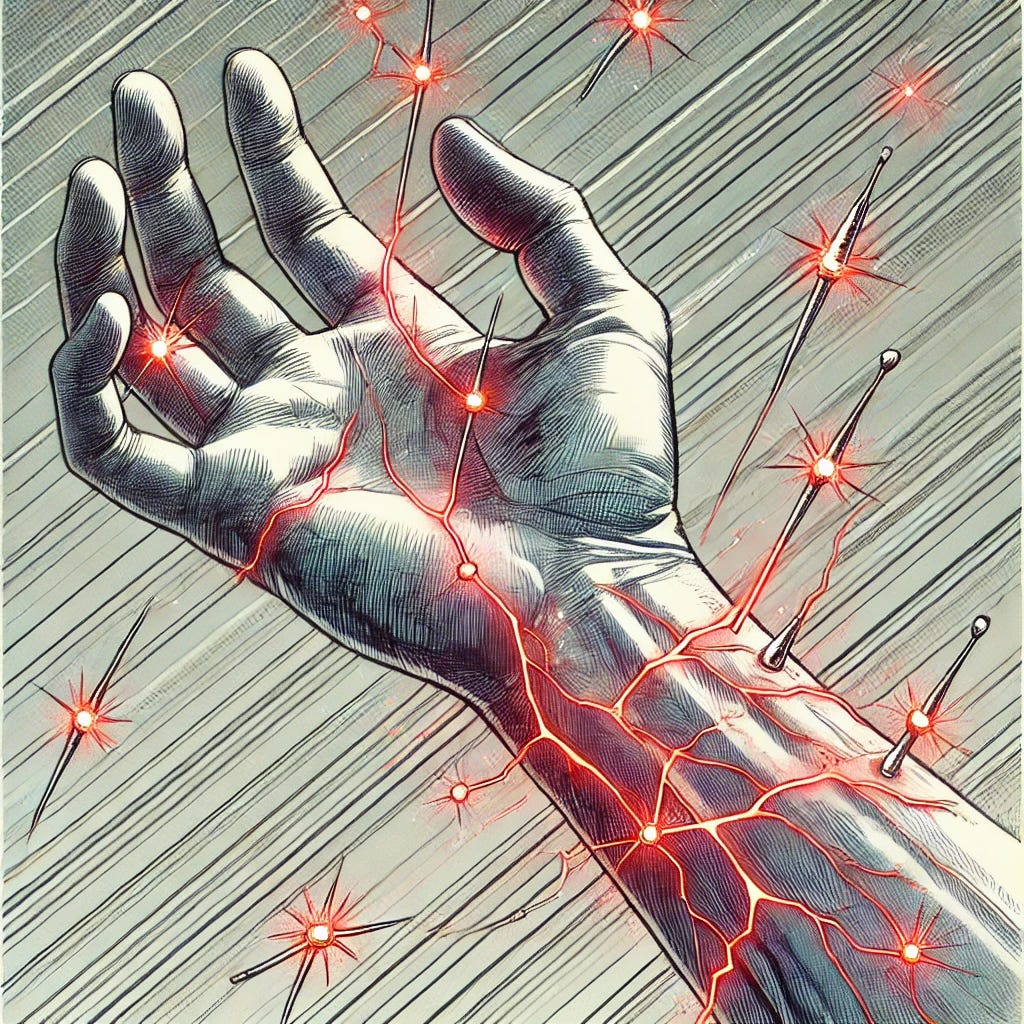

People will most often describe this feeling as pins and needles, presumably because it feels as though tiny, sharp objects are poking at you over and over. Having been poked by an actual needle more than once, I’m not sure this is the best analogy, but it seems to have stuck.

This feeling is called paresthesia, from the ancient Greek para (alternative or abnormal) and aisthēsis (sensation). You’re almost certainly familiar with how paresthesia feels—virtually everyone experiences the temporary form.

When my hand falls asleep in the dentist’s chair, one of those long tubes running from my fingertips all the way up to my brain gets a kink in it. That’s not precisely right because nerves aren’t quite as simple as very long, singular tubes—but the idea is going to help us to visualize what’s happening.

When you feel these pins and needles in your hand, there’s a signal that travels up those same nerves, all the way up to your brain. If there’s a kink anywhere in that long tube, the smoothly flowing signals that normally arrive are disrupted, a bit like TV static or feedback.

If you get the long hose unkinked, your hand functions normally (after a few seconds of the feeling lingering, sometimes far too long for comfort). Similarly, if you cut the flow of blood off to a particular area, pins and needles creep to the surface of your skin in the area that’s cut off.

When I wiggle around in my dentist’s chair, I’m manipulating that tube so it’s no longer kinked, and/or possibly so that the information carried by said tube to my brain doesn’t get interrupted. Visualizing this while having someone peer into my mouth is one way to keep myself amused.

It’s interesting to feel something in your hand that isn’t caused by your hand, isn’t it? This is yet another reminder that everything we experience—literally everything—runs through the filter of our brains inside our skulls. This imperfect system means that you can feel things that aren’t really there, and it means that the signal can be easily interrupted.

This de-kinking of the hose solution only works for temporary paresthesia, like what I experience when my nerve is compressed at the dentist. However, there also permanent paresthesia that affects millions of folks worldwide.

If you know much about diabetes or MS (Multiple Sclerosis), you’re probably already nodding your head with understanding. These are diseases that affect both the body and the mind, and nerves are the pathways between those two domains.

Another really common cause for long-term paresthesia is carpal tunnel syndrome. Think about compressing that nerve that sits under the corner of your hand as you type, and then imagine doing that over many decades. Because the signal chain ultimately gets broken, you end up receiving chaos instead of order.

Paresthesia is fascinating enough, but it’s not the only way people use the phrase pins and needles. In fact, you might hear the slightly longer on pins and needles more often than you hear this phrase any other way.

That’s the power of a metaphor. Those little prickles you feel when your hand falls asleep are a lot like the prickles of anxiety when you approach someone you’re romantically interested in, or when you’re applying for a new job.

No actual pins or needles are stabbing you in the gut, but maybe it feels closer to that than to anything else we can articulate. Maybe we should invert the phrase for good to needles and pins whenever we’re talking about this latter feeling of anxiety or unease. By contrast, we can keep pins and needles for the dentist’s chair.

I was on pins and needles waiting for this essay to drop.

I pictured a Hindu yogi on a bed of nails