People are historically very, very bad at predicting the future.

Yogi Berra is widely regarded as one of the greatest catchers in Major League Baseball (MLB) history. In his 19 seasons of professional baseball, he was an all-star 18 times. He was American League MVP three times, and maybe most impressively of all, he racked up ten World Series championship wins with his team, the New York Yankees—the most by any MLB player ever.

Even with all these accomplishments, Yogi is better known today for his wit and wisdom. One of this best Yogi-isms is about trying to predict the future:

Yogi had a point: the future is a real challenge.

Some of the most famous predictions that seem silly to us today center around the world of technology. We can see whether or not everyone is using hoverboards or using their minds to communicate. In other words, it’s easy to see whether the prediction was right or wrong.

Here’s a famous example:

"I think there is a world market for maybe five computers."

— Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, 1943.

Who wants to be the one to tell him? Today, we have something like 50 billion computers if we count smartphones and IoT (Internet of Things) devices. Even counting only desktops and laptops gives us a number in the low billions. Watson’s specific quote has since been pushed back for accuracy, but there is little doubt that the sentiment at IBM was toward a few very, very large machines.

Another good one:

"Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons."

— Popular Mechanics, 1949

Technically, this one gets partial credit because it clears the very, very low hurdle set by the prediction… but the idea that computers might weigh less than a ton really was shocking during the 1940s. This was the era of ENIAC and other computers that took up a high school cafeteria’s worth of space.

An average laptop today might weigh about 4 pounds, give or take.

Of course, smartphones fit in your pocket, and you probably have one close by you right now. They weigh more like five ounces or so, and there are far smaller devices than smartphones that still qualify as computers, like the newish AI pins, and smaller still microcontrollers that live inside of everything from medical implants to cars.

The smallest current computer called the Michigan Micro Mote. It’s smaller than a grain of rice, and even smaller than some grains of sand.

One more quote about computers:

"There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home."

— Ken Olsen, founder of Digital Equipment Corporation, 1977.

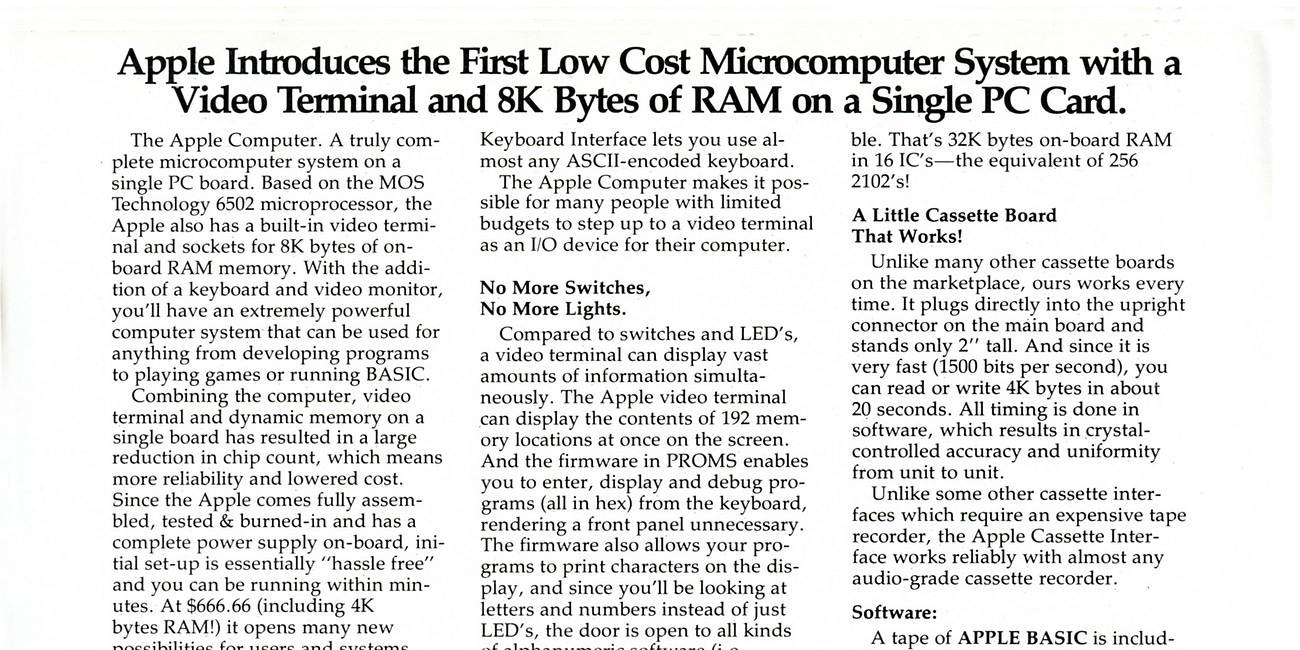

If you’re reading this last one and you’re thinking that Ken Olsen in particular should have known better, you’re not wrong. DEC in 1977 largely focused on mainframe computers for businesses, though, so Olsen seems to have missed the personal computer revolution that had been launched the previous year:

The quotes I provided about computers aren’t by random people on their couches. These are experts in their respective fields: Tom Watson was positioned at the absolute top of the computer industry in 1943, and Popular Mechanics was a hub for electronics enthusiasts in the late 40s and early 50s.

Of course, one prediction about the future of computers has proven to be eerily accurate and creepily prophetic: Moore’s Law. The best computer chips have, in fact, continued to increase in complexity while coming down in price, and the pattern so far has proven remarkably predictable.

The laws of physics used to make the universe seem very predictable. Newton showed us that if you knew a few things like mass and speed, you could eventually take human beings safely to the moon, and a great deal more. Newton’s laws are incredibly intuitive, and you can run experiments yourself to help reinforce how satisfying it is to predict that something will fall at a certain rate, for instance, and then to watch that very thing happen.

However, even Newton’s uncanny theory wasn’t able to answer a few questions, only made evident once we could measure things more accurately, like the orbit of Mercury.

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity augmented our understanding of the universe from one direction, answering the question about Mercury’s orbit handily. Meanwhile, quantum mechanics started giving us a way to make some very bold predictions about what sorts of particles we should find. If we found a particular particle, we knew our theory was going in the right direction, consistent with reality.

A theory is only any good if you can use it to make predictions about the future. Up until that point, it’s more like a cool idea, bro. You need to be able to test it out and prove that it works in all situations, too, not just once or twice.

Newton’s Theory of Gravity was useful because it got us all the way to the moon. Einstein’s Relativity is useful because it allows us to use GPS devices to track where we are on the planet with fantastic precision, something impossible without taking into account that the nature of reality is different at very high speeds.

Then, there’s quantum mechanics, which allows us to make the most accurate and precise predictions in all of science. We’re talking agreement out to ten decimal places here. Without this depth of understanding—and this ability to make very specific, accurate predictions—we would not be able to keep up with Moore’s Law.

Predicting technological innovations based on the laws of physics might seem like fruitful ground, but few imminent physicists saw the explosion in our terrestrial connectivity by way of the internet. We predicted some things far, far later than they actually happened, like how Star Trek: The Next Generation introduced something that looks suspiciously like an iPad during the 80s, but as a 24th century toy, not an early 21st century gadget.

On the other hand, we predicted that we’d quickly solve other problems that have proven intractable. The Jetsons sure did make it seem as though we’d have flying cars by now, but cars on four wheels still dominate our landscape, and they haven’t really changed all that much over the last hundred years or so.

We don’t have infinite energy, and we don’t have an army of robot slaves. We do, however, have much more useful virtual librarians (like Google search or large language model chatbots) to help us find the things we’re looking for, and for every metric where we’re way behind, we’re just as far ahead by another measure.

Predictions are, indeed, tough.

Have you ever made predictions about what sort of technology we’d have in the future? Have any of these come true, and have you been way off on any guesses? Let’s share!

I'm gonna go ahead and be the "Well, actually...." guy here and share this old article of mine where I not so much debunk as put in context some of these so-called "bad predictions": https://www.toptenz.net/top-10-famously-bad-predictions-experts-didnt-actually-make.php

All three of yours are on my list, along with 7 others.

But that doesn't take away from your point. Predictions are hard. Unless you're predicting that Daniel will be a wise-ass. In which case, you're always 100% correct.

It's a good thing most predictions don't come true. In the prototype days of science fiction in the 19th century, many authors wore their politics on their sleeves and concocted utopians where white men solved their societies' problems easily and subjugated everyone else to their rule. I would be delighted to inform them that this did not happen (at least the former part).