Alexander was about to completely change the world.

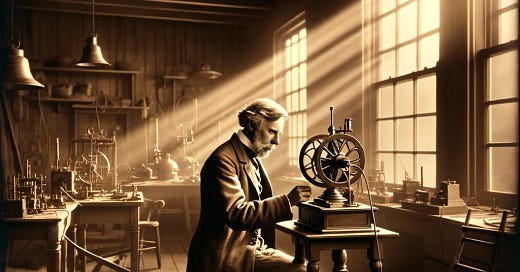

No, not that Alexander. This was March 10, 1876, and Alexander Graham Bell was working in his lab, conducting experiments with his newly invented device. Meanwhile, Thomas Watson was busily working on his own lab tasks in another room.

Bell’s lab was a very frenetic place, full of energy and ideas. Unlike Edison’s Menlo Park, the lab was small and crowded. There were always little experiments running, sometimes several at a time, and it was easy to lose track of time there.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bell spilled some acid he was working with in a specific experiment, and he needed to clean it up, and fast. The only problem was that one of those experiments he was running needed silence—a shout from a human voice would surely destroy the delicate work done so far.

Out of other options, Bell tried the one thing that could maybe, conceivably work. He spoke into the little funnel of the device he was working on.

Mr. Watson, come here. I wan…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Goatfury Writes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.