In the 1880s, the Supervisors of the Census had a huge problem.

Every ten years, the US Constitution mandates that a census takes place. This is so that Congress knows how many Representatives each state gets, along with federal funding and some other important bureaucratic work.

Back when the census began—in 1790—things were a lot simpler. First, only the most basic personal information was collected, like age and gender, and second, there just weren’t as many people in the United States.

Over time, the population grew rapidly (from 3 million to 50 million by 1880), and so did the questions that needed answering. A permanent US Census Bureau was still a couple of decades away, but the problem was becoming urgent: there were just too much data to sort. 1790’s census took about a year and a half to sort. As the complexity of the questions and the population both grew, the amount of years this process took continued to accrue.

Eventually—by 1880—it became evident that the existing process was going to take longer than ten years. The very idea of doing a census every ten years, and then not having the data tabulated before the next census took place was too much for the Census Office.

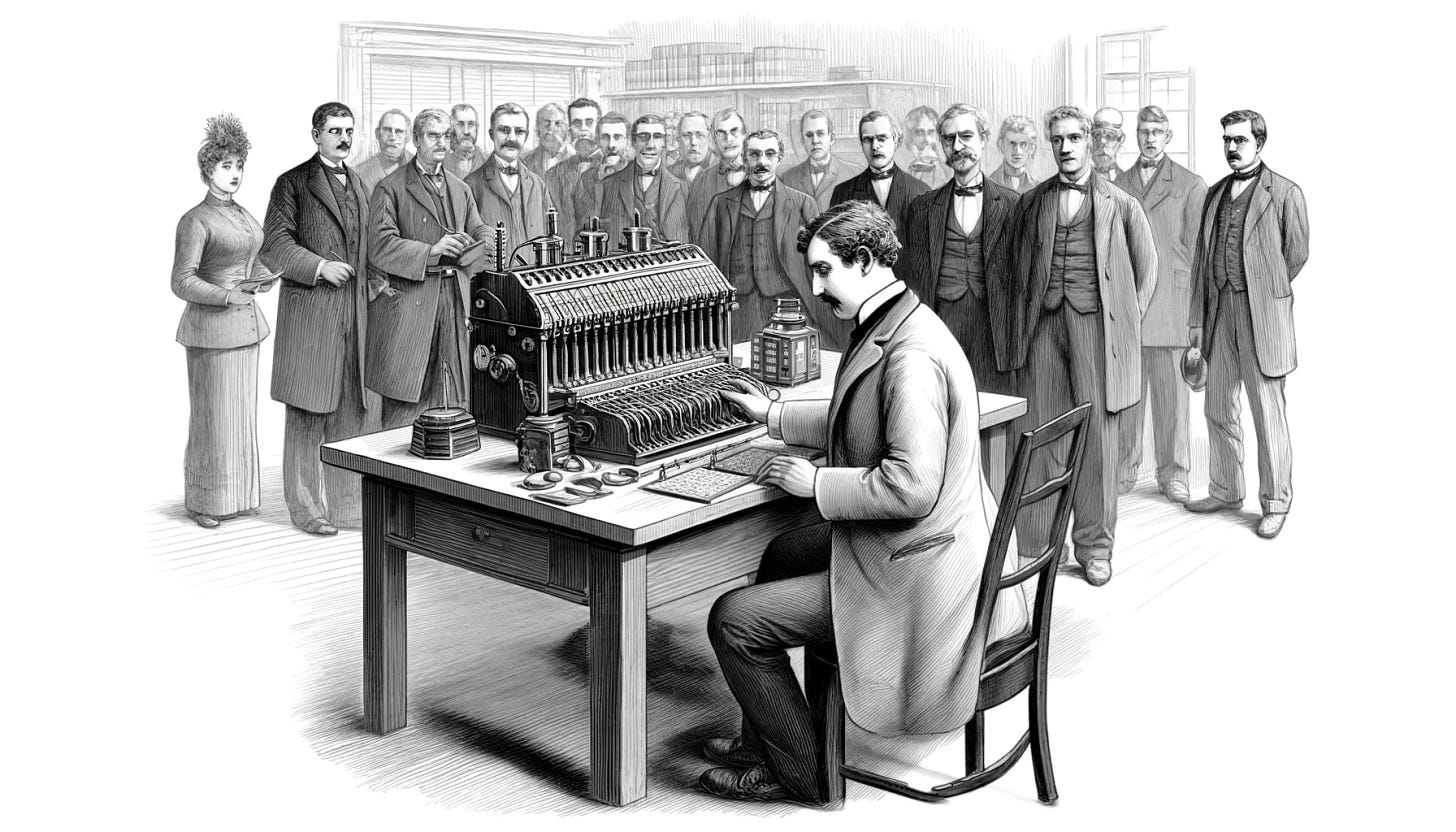

In 1888, they decided to run a competition to find a better way to tabulate data. Herman Hollerith had recently worked for the Census Office, and he had seen first hand the insurmountable task of counting all those metrics and putting them in the right place to be analyzed.

His process was centered around a curious invention from the start of the 19th century, the Jacquard Loom. In 1804, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, a French weaver and merchant, patented a design for a loom—a weaving machine—that did not need a skilled operator, but instead relied on punch cards.

These rigid cards had little holes punched in them, and each hole allowed a little rod to poke through, which caused a particular thread to be woven in a particular spot, and at a particular moment in the process. The pattern would be woven right onto the fabric in real time, an early example (but not the earliest!) of a program running.

While Jacquard’s loom was purely mechanical, Hollerith introduced electromechanical components. This meant that the holes in the punched cards didn’t need a little rod to slide through in order to activate a weaving thread, but instead could rely on a simple circuit being completed.

In Hollerith’s machine, a human would feed the card in manually, one at a time. As the card slid through the machine, a series of spring-loaded pins descended onto it. If a pin encountered a hole, it passed through and made contact with a pool of mercury below, completing an electrical circuit.

This completed circuit would trigger a little lever to flip, advancing a little counting dial forward by one notch. You could enter a bunch of data, then just glance at the corresponding knob to see how many men over 40 lived in Virginia, for instance.

Hollerith founded a company centered around his invention. At first, this company was called the Tabulating Machine Company, which seems like a really appropriate name. Eventually, the Tabulating Machine Company merged with another company to form CTR (the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company)

CTR was later renamed International Business Machines Corporation, but most people today just think of them as IBM. Hollerith’s punch cards were at the very center of IBM’s operations for decades.

All inventors stand on the shoulders of giants, building off of their predecessors and creating things that wouldn’t exist without all those earlier inventions. Hollerith’s contribution would not have been possible without Jacquard’s loom, of course, but there also needed to be a deep and vast understanding of electromagnetism, and that was only just now starting to become available.

The US was a very good place for the study of the practical applications of electricity, with Edison’s Menlo Park coming into its own as a leading-edge research facility, unlike anywhere else in the world. Without this innovative spirit, it’s unlikely that Hollerith would have gotten very far along at all.

Hollerith stood on the shoulders of many others, but then even more stood on his shoulders. IBM’s punch cards were still the dominant paradigm in computing when my parents were in college during the late 60s and early 70s, and it wasn’t until the personal computer revolution of the 70s that punch cards were finally left in the dust.

Many of you (my readers) have shared your experiences with using punch cards for computing. Are there any of you out there who used punch cards in a non-college environment? Did you ever work in a place where you signed in for work with a punch card (spoiler: I did!)?

I actually had a part-time job where you clocked in / out using ink-based punchards. But if I'm honest, it felt very antique already then (early 2000s).

Also, "Supervisors of the Census"? Looks like Marvel is finally running out of ideas. 2/10, would not watch.

Yep. I punched into work.

Plus when I started in IT in 1979 we had a punch room to punch our COBOL onto cards, we just did the control cards. Paper tape was still being used too.

We had simple punch machines in the office to correct any cards with errors. Getting a program coded error-free took ages as every turn around was a day.