Trying to imagine 13.8 billion years of the universe isn’t something that comes naturally for human beings. Our hearts beat once a second, give or take, and we sleep for a few hours at a time each day.

Years gradually drag by for us, and then decades. We might even live a century, but trying to wrap your head around the scale of billions of years certainly doesn’t come easily to anyone. Our bodies are attuned to the scale of our habitat, and it’s fair to say that our minds are also wired to think within the time scale of a human lifespan.

As a kid, I loved learning about how things worked, but like my fellow human beings, thinking along these time scales wasn’t natural for me.

Carl Sagan came to my young brain’s rescue with his iteration of the Cosmic Calendar. Instead of trying to think directly about this insurmountable time-mountain, try using an analogy to something much more familiar to us: one calendar year.

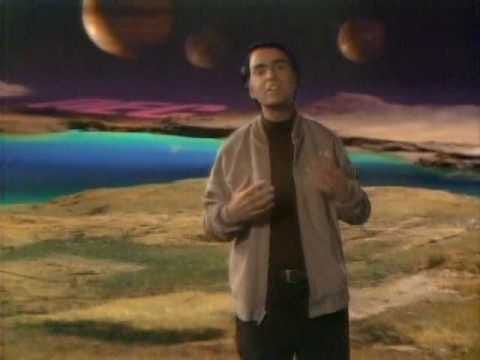

Here’s Sagan, explaining things as only he could:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Goatfury Writes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.