If you want to feed, house, and clothe 8 billion people, you’ve got your work cut out for you.

Or rather, we’ve had our work cut out for us this whole time. We’ve been trying to figure out how to accommodate more and more humans ever since we’ve been human.

Today, I just want to call attention to how we’ve managed to do it.

Let’s start with food. A hundred thousand years ago, we were survivors and scavengers. We could thrive on a huge variety of food, and our diets changed based on what was available.

Little bands of humans stuck together and shared food, and this made a lot of sense: a small community or tribe could have some small economies of scale, with some division of labor allowing some specialization. You ended up with a few expert hunters in each tribe, and maybe one or two expert butchers, capable of efficiently carving any corpse with sharp stone tools, then feeding everyone with the nutrient-rich meat.

You’d also have amazing gatherers who knew which plants, nuts, and fungus to bring back to camp, and able to identify dozens (if not hundreds) of different plant species.

The plus side was that we were getting a wide variety of foods, with a healthy mix of animal and plant macronutrients, and no processed foods or refined sugars. The minus side was nearly a dealbreaker for our species: food security was very low.

This meant we were always on the move, and always susceptible to the land running dry, so to speak. If there were no nuts and berries to pick, and no tasty animals to kill nearby, then we had very limited options at hand. Once we ran out of whatever limited stores we had, we tended to starve to death.

For this very reason, a gradual evolution toward farming began in earnest something like 10,000 years ago, but this change was slower than you might have been led to believe. It’s not like a switch happened overnight, and I think it’s a bit of a misnomer to call it a revolution per se… but only in the sense that everything didn’t change overnight. The effects were certainly revolutionary.

The Agricultural… Revolution?

Once upon a time, our ancestors hunted animals for food, and foraged for plants they could eat. Life was nomadic, and each day was a quest for sustenance.

Feeding lots of people by growing crops introduced a lot of negative things, too. We started to have more diseases as animals we were going to eat needed to be close by, often sleeping in our houses. Our diets were also pretty crappy compared to those of our prehistoric ancestors, but there was one really big up side to all this farming: consistency.

You might have to eat nothing but bread this winter, but bread was better than starving to death, so human populations were able to continue to grow, far beyond the lifestyle our hunter-gatherer ancestors could have possibly sustained with the resources on the planet.

Over the centuries since this creeping revolution began, we’ve managed to expand crop yields dramatically through a variety of ways. One of these more common-sense methods was to rotate the crops so that the nutrients in the soil had a chance to replenish, and this idea led to a deeper study of macronutrients needed for food to grow.

This led to a better understanding that nitrogen was a major component of food, and it turned out that you could get nitrogen from the air instead of from the ground. So was born the Haber-Bosch process, one modern conclusion to the nutrient shortage brought to our attention long ago. Some argue that this process is the reason several billion of us are alive today.

Saving Half the World

In the movie Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos infamously snaps his fingers and (spoiler alert!) half of the life in the universe dies. Thanks a lot, Thanos!

Food security and diversity continue to be incredibly important issues for us today, but food isn’t all the many need, as Mr. Spock might call them.

We also need a lot of water.

If we had to move from place to place due to food scarcity, you can bet this was even more prominent whenever water started to run low. We had no choice but to follow the freshwater: 100,000 years ago, we all drank from lakes, rivers, streams, and maybe a bit from rainwater we had collected in makeshift containers.

Not only might a drought kill you, but a life-ending parasitic infection might also be in the cards. Give this a bit of thought the next time you’re pining for the good old days of prehistory, and try to keep this in mind the next time you take a sip of fresh, clean water.

In order to address this, we started in earnest at the same time as farming. That’s because you need way, way more water to grow crops than you need to drink, and it was necessary to have large amounts irrigated in from freshwater sources. One notable thing about bringing the water in this way was that we didn’t have to move nearly so often.

That meant we could finally settle down and form little towns. After all, if we didn’t need to pack everything up and flee because we ran out of food or water, maybe it was easier just to stay here. On a personal note, I don’t enjoy moving, even with the luxury of a U-Haul truck and a tow dolly. Our ancestors must have suffered a great deal any time they picked up their roots and planted them in a new location.

Settling down into cities (as they became) introduced all kinds of new diseases and shortened human lifespan for thousands of years before dramatically raising it again, but it also allowed us to continue to survive and reproduce. And: reproduce we did.

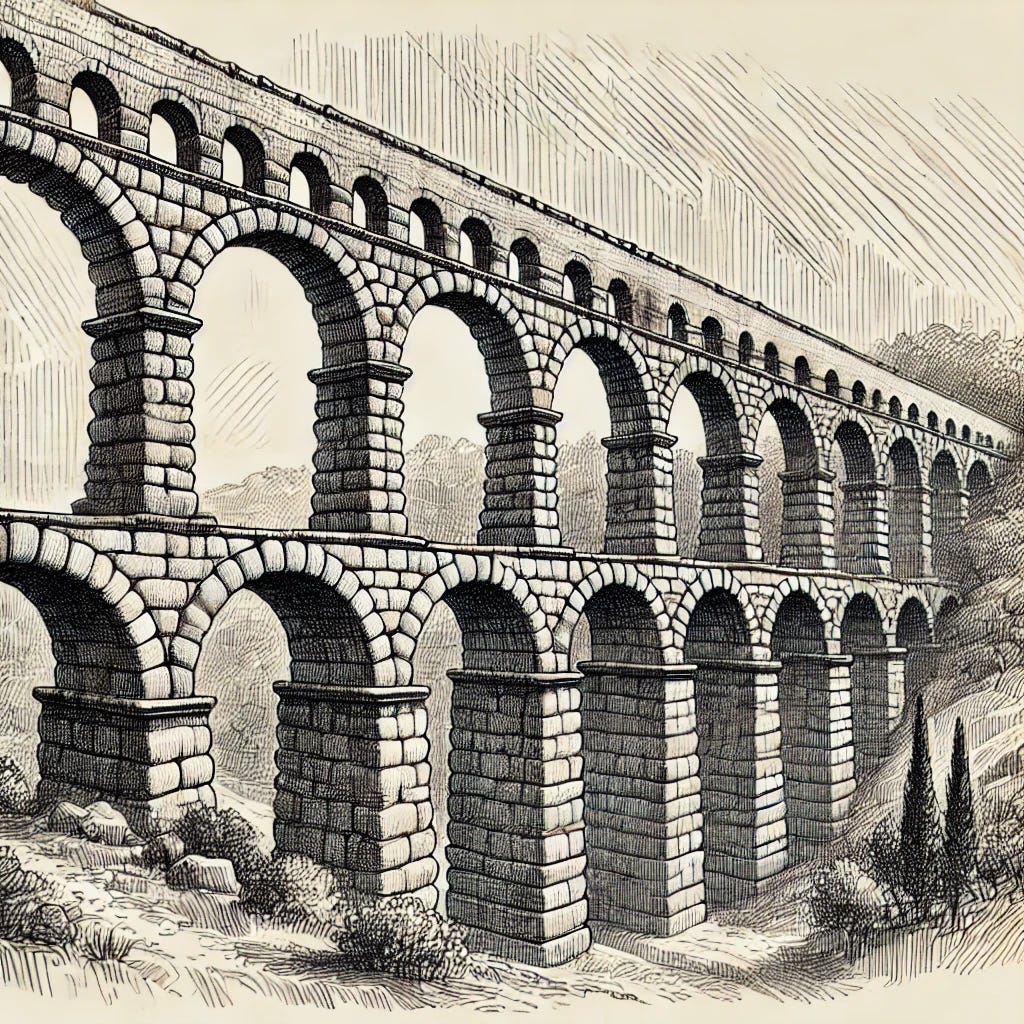

As we grew, so did our water needs. By the time of the Roman Empire, incredible structures known as aqueducts had appeared. These concrete monsters brought water from miles away in many cases.

The precision of these aqueducts is impressive: imagine trying to construct something several miles long, where water continuously flows very, very slightly downhill. Now imagine doing it with a bucket of concrete and no electricity.

Rich Romans even had running water inside their homes, and many other ancient civilizations developed amazing waste management systems, but it was nearly two millennia before most of the world had running water in their homes.

Speaking of homes, all these people needed somewhere to live.

100,000 years ago, our ancestors did not build structures. There were no buildings, although there might have been some lean-tos or temporary shanties built alongside existing structures. Mainly, we found stuff like caves and tree covers and just made do.

Remember, nobody much was trying to settle down or tie themselves to any particular geography, especially since food or water might run out any day.

When the slow food-and-water revolution happened around 10,000 years ago, we realized we could have both food and water in one place, but we needed more permanent settlements than those shanties. Well before the agricultural revolution was in earnest, monumental stone architecture was already happening:

Göbekli Tepe

When Klaus Schmidt first set foot on a dusty, nondescript hill in Southeastern Anatolia in 1994, he had no idea he was about to rewrite our early history.

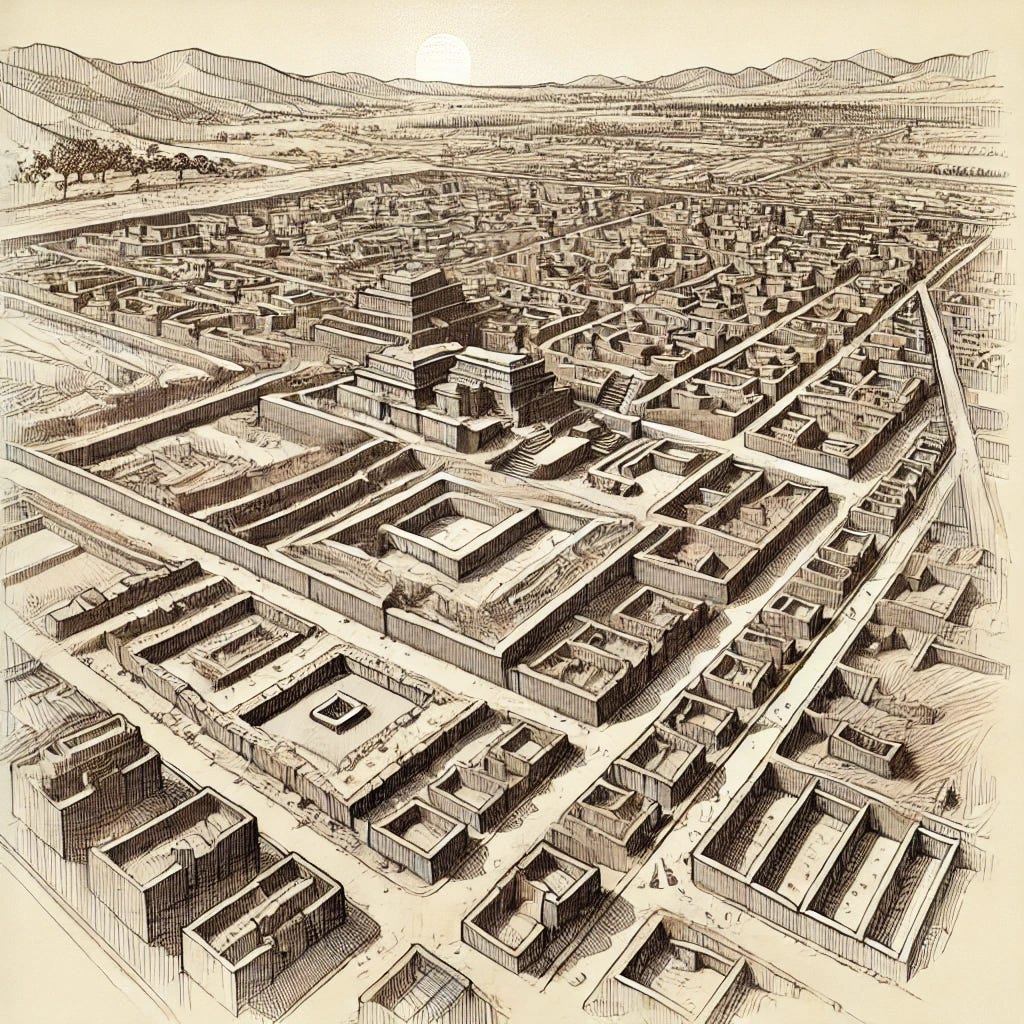

As the infrastructure problem (food and water supplies) was solved in different areas of the world, more and more settlements began cropping up. Tenochtitlan in Mesoamerica saw a million inhabitants living on an artificial island, long before sanitation or modern medicine had been introduced.

Mohenjo Daro, the capstone of the great Indus Valley civilization, saw a clearly planned city with careful rectangles for individual dwellings, all laid out in a grid pattern. There was even running water and sewage, and this was 4500 years ago.

Unfortunately for the rest of the world, Mohenjo-Daro was lost completely to the other civilizations of the world for thousands of years, lying buried until its rediscovery in the early 20th century. I can only imagine how much better medieval sanitation might have been if this city had not been lost to time.

Today, post-industrial revolution, we have different materials and techniques for building homes, but we clearly don’t have everything figured out. For one thing, there’s a gigantic issue with equal access to all of these necessities. Although it was impressive for the Romans to tote fresh water into Rome from miles away, the problems facing today’s world are many times tougher.

Do we have it all figured out now? Hardly.

The challenges of feeding eight billion people have involved serious trade-offs, since the processes to unlock nutrients in the soil all burn fossil fuels, so we are forced to continue heating the planet in order to grow more crops to feed more people. Water scarcity is still a major problem all over the world, although the problem is much more acute in the global south, and sheltering everyone continues to be a major challenge for all governments and nations.

Trees don't grow to the sky, and there are serious limitations to the potential human population. This is probably a good thing, since we seem to have the ability to make problems that are tougher and tougher to solve as time goes on.

Have you ever had to deal with food, water, or shelter security issues? If you're comfortable with sharing some of your stories today, I'd love to hear them. As a planetary species, what should we do to make sure everyone can have access to shelter, food, and water?

Great, now I'm hungry and need a drink.

In the words of famous nutritionist Marie-Antoinette, "Let them eat cake."

Problem solved. Easy.