Ever listen to someone lecturing you about a subject you already know about?

Maybe they’re telling you everything they think you need to know about spontaneous sync and how metronomes (or pendulum clocks) will start ticking at the same time, even if you set them deliberately off-kilter. While they’re lecturing, all you can think about is how you already know about this subject.

You can’t wait for them to shut up so that you can show off what you know. You want to point out that spontaneous sync is everywhere in nature, not just in mechanical systems like clocks or metronomes. Biological systems like fireflies can sync up to spontaneously tick in unison, quantum mechanical systems at the smallest scales will synchronize at once, and astronomical systems like the Earth and the Moon can eventually line up all on their own.

You want to explain how these strange and seemingly unconnected phenomena are all explained by something called the Kuramoto model, which simplifies these systems into sets of coupled oscillators.

In your enthusiasm to show this person just how much you already know, you’ve missed the entire thing they wanted to share with you. It’s about how you need a critical mass of these oscillators for a system to sync up, but there’s nothing gradual about this transition: add nine more oscillators, one at a time, and nothing happens... but add that tenth one, and then the entire system syncs up. This touches on emergence, your favorite subject at the moment.

You’ve missed the entire thing they were trying to share with you, but now you get to show them how smart you are. Congratulations, I guess?

The above person is me. I’m talking about the one who can’t wait until the other person stops talking. Sure, that second person is me some of the time, too: that’s what I’m doing right now, hopefully—sharing useful information with you in a manner that’s easily digestible.

However, I’m the first type of person far more often than I’d prefer.

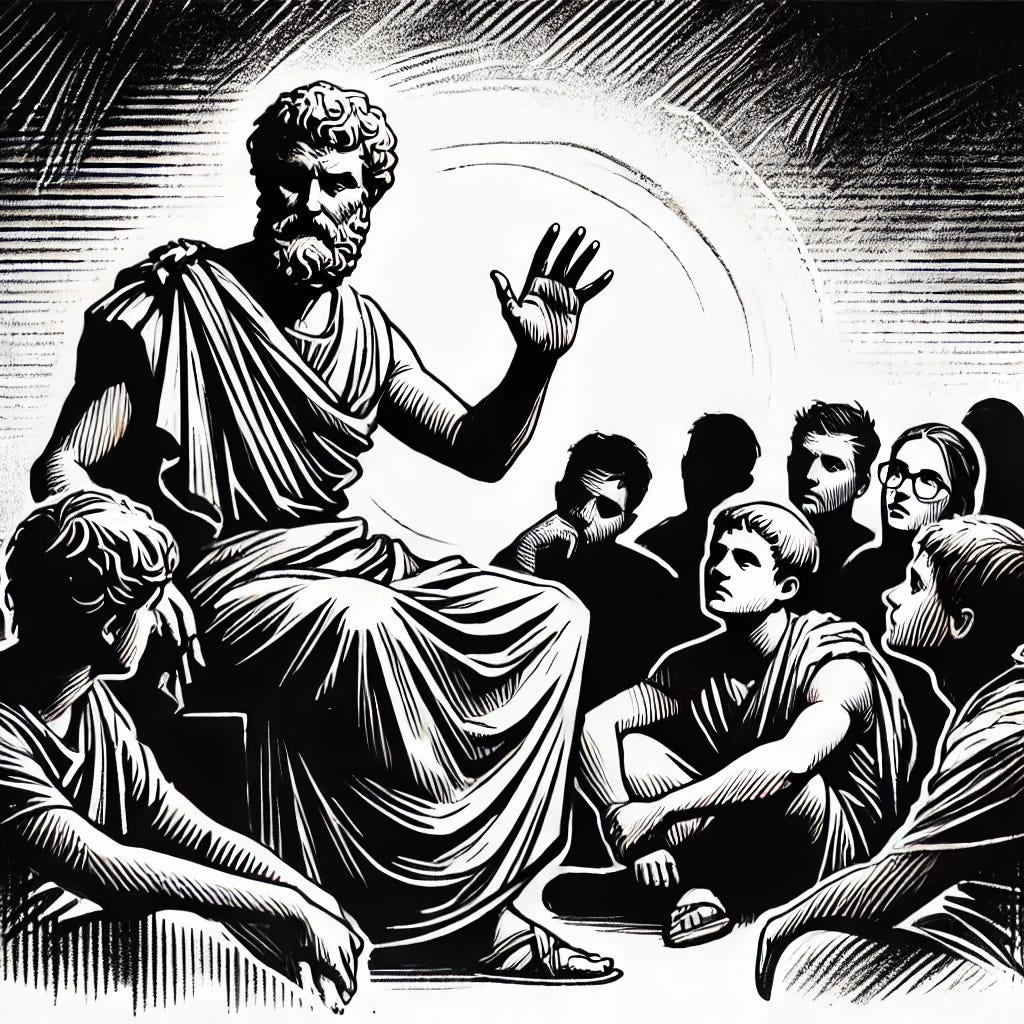

Epictetus, a Stoic philosopher who lived during the heyday of the Roman Empire, had something to say about this type of interaction. His pithy quote sums it up nicely:

It is impossible to learn that which you think you already know.

Writing 1900 years before Dunning and Krueger made their findings widely available to the public, Epictetus absolutely nails the idea in a short sentence. Like the other Stoics, humility and self-awareness were placed at the top of all values. Epictetus and the Stoics understood that there were limits to human knowledge, and it was dangerous to ignore these limits.

Epictetus has another quote that might be even better:

We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.

His own life provided a lot of interesting lessons in patience and self-control. Born into slavery, he quickly learned to observe the powerful individuals he served, and the system surrounding him. As a captive slave, Epictetus had the silver lining of seeing powerful people rise and fall all around him.

As a teacher, he saw students trying to focus on a Stoic path, and how they failed or succeeded at various turns. He saw first-hand what kept students from learning, too. He knew that arrogance and impatience consistently drew his students away from understanding the world.

I, too, am a teacher. Like Epictetus, I’ve seen thousands of students come and go over the decades. I’ve seen the blue belts rolling their eyes (mentally) as I point out a detail they’ve already heard a dozen times, and recognize that the ones who have gotten better are the ones who have gotten this mindset out of the way most successfully.

Humble and hungry might be a good description of the mindset that seems to work best. That’s the mindset I’ll be working on over the next decade, trying to remember that I, too, have two ears and one mouth.

I'm fast realizing, in trying to write about stoicism, I already do with Polymathic thinking.

Ugh, I already knew what you were gonna write, so I didn't even read the article, dude.

I'm a blue belt at knowing everything, for real.

But you already knew that, didn't you?