“I’m against all technology,” the imaginary stereotype sitting next to me says.

What about that those glasses you’re wearing, I ask? Those are technology.

“That’s not what I mean! I’m talking about technology that impacts privacy. You know, technology!”

So, like a telescope?

“No, no! That’s not what I mean at all. I’m talking about the type of thing that completely disrupts and changes society when it’s introduced.”

Like writing?

“No, I’m talking about technology here, not some ancient inventions or something!”

I won’t belabor my pretend conversation with someone who doesn’t really exist, but let me just point out that this point of view definitely exists. That is, there is a prevalent belief out there that technology is something very modern and exclusively digital.

The truth is that every single idea we’ve kept and then passed down from one generation to the next—all of those ideas are a form of technology. Every beneficial idea that paved the way for even better ideas represented a stepping stone along our technological pathway.

Controlling fire might not have been our first invention, but it certainly ranks among our most important. At least a million years ago, our ancient ancestors figured out that burning wildfires could be controlled, then used for light and heat.

Over time, we figured out how to harness the heat better and better, leading to kilns, then ovens, and eventually to nuclear reactors. None of these steps upward would have been possible without the previous steps. I told this specific story a bit here:

Harnessing Heat

Some time around a million years ago, give or take, our early human ancestors (or cousins, maybe—we’re not sure) started playing with fire. Homo erectus undoubtedly came across natural fires at many points, ultimately gradually figuring out how to control and maintain a fire on their own… and then start them.

Controlling fire was kind of like a leap from zero to one. In an evolutionary flash, we went from having to spend all day chasing calories to having leisure time. Fire helped us to digest our food, unlocking vital energy from what we ate in ways that weren’t possible prior to the discovery of fire.

The rest of the leaps upward were from one to n, meaning they began somewhere, and then leapt upward to a higher state. This is a really useful distinction if you’re looking at human innovations and inventions, because they almost always stand on the shoulders of giants.

Our next zero to one leap was almost certainly language, and it’s a doozy. I’m using language right now to talk to you by way of a magical medium: the internet. As soon as this tech was invented, we started to do things that were far beyond that of previous humans. By talking to one another, we could pass more complex ideas back and forth, even preserving knowledge from one generation to the next.

Without the stability and leisure time fire provided us, it’s doubtful that language would have evolved, so you can sort of see how each invention builds on the last one, and nothing stands in isolation.

Anyway, language eventually got us to writing when it merged with another great zero to one invention: art. Once we could write ideas down, we started to share complex concepts with people who weren’t yet born, with people we would never even meet. The telephone game of oral traditions was replaced by a more precise mechanism for recording events and observations, beginning about 5000 years ago, and continuing to the present day.

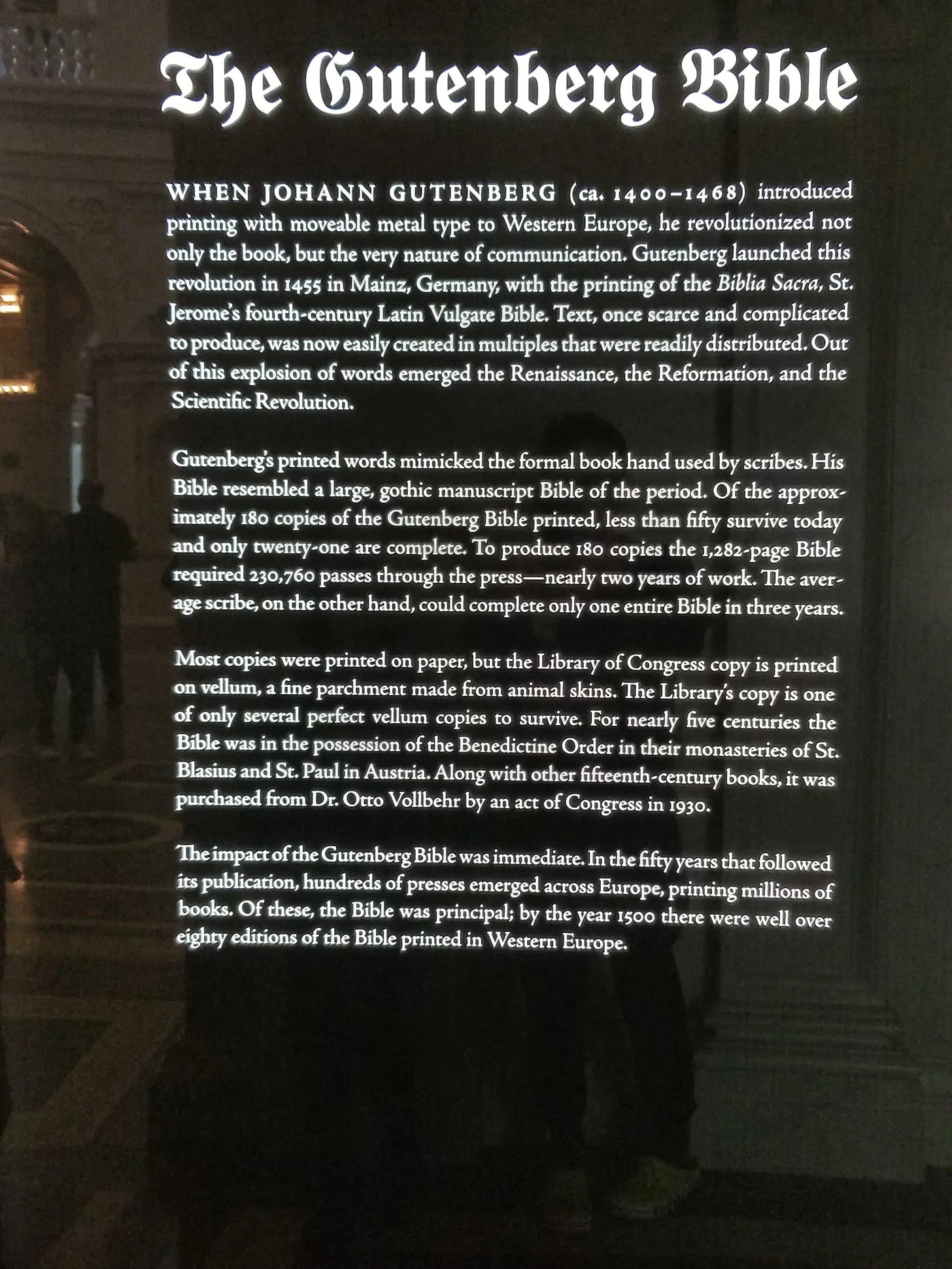

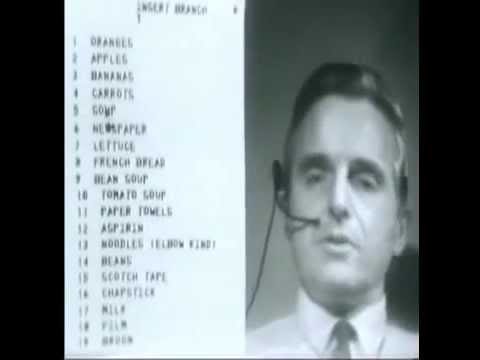

Writing was good for spreading ideas, but it wasn’t until another one of those one to n inventions came around that we saw things take off exponentially. That invention was Gutenberg’s printing press. I snapped this pic at the Library of Congress:

In 1300, there were perhaps several hundred thousand books in existence, every one of which was hand-written. By 1900, there were hundreds of millions of books, almost all printed by a machine and much easier to read than a hand-written counterpart.

Then, the internet provided us with another way to transfer ideas around the world. This was an incredible innovation, but it was certainly one to n, building off of previous communication technology and methods to exchange information. Today, the amount of information we exchange is almost unimaginably greater than that from 1900.

Every day on the internet, more information flows back and forth across the world than all the information from all the books ever published before 1900, and this is mind-numbing. We aren’t really equipped to think about that sort of exponential growth with our terrestrial pea-brains.

You can read a bit about the incredible earliest days of the internet here:

Even still, while the internet is technology, so are books. The printing press represented a huge leap upward during the late 15th century just like the internet did during the late 20th century.

Go back even further and we can see that writing also represented a huge leap upward for information storage and exchange, and oral language did the same thing long before writing.

In other words, it’s all a continuum, and anyone who says they hate technology is actually using technology to make their point, even if they’re just speaking out loud with a language that was invented by humans, then passed down from one generation to the next, and eventually taught to that person.

The imaginary Luddite in front of you doesn’t mean to be a hypocrite, they really can’t help it as they walk into the coffee shop where you’re meeting them, wearing tech (clothing) invented by our ancestors, and using technology (money) to pay for their coffee, itself a product of a multiplicity of technologies.

You have a seat at a table with chairs, themselves a product of technology. You enjoy a friendly conversation (tech) while appreciating the rustic nature of the coffee shop, built from the knowledge of giants standing upon giants.

Hating technology is, in a very real sense, hating humanity. It is our ability to share knowledge from one generation to the next that makes us who we are, and we call this ability technology. Tech isn’t just the latest iPhone; it’s every idea we’ve ever had and shared with one another.

It is the essence of who we are.

They're in good company. Plato railed against writing vs. oral traditions, scribes reacted to the printing press as inartistic and mechanistic, painters hated photography... hell photographers hate on cell phone photos.

Somewhat echoing some of the previous comments, perhaps the sweeping statements about ’hating’ digital technologies, instead of eyeglasses or chairs, etc, arise from an intuition that there is something different and not entirely comfortable in how they capture and direct our attention. And how technology development divides us into makers and users - and it’s rarely the makers who are the haters because they (unlike the ’mere’ users) feel a sense of agency with the tech they are building. As a recovering technologist, I’ve tried to write about those aspects.