Golden Spikes

Prior to the buildout of railroads, it took months to get from one side of the US to the other. After, it was cut down to about seven days.

Here’s Andrew Sniderman 🕷️ writing about the moment the east and west coasts were finally connected by railway for the first time, through the lens of a specific person who had to endure harsh conditions to get the job done:

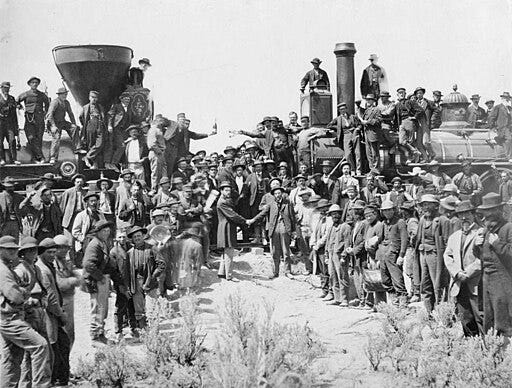

After fifteen months of drilling from both sides, the crews finally met in the middle. It was November 1867 and Shi was there watching as a small circle of daylight appeared, filtering brighter as the dust settled. By the summer of 1868, trains were crossing the Sierra through Tunnel Six. A year later, at Promontory Summit in Utah, Central Pacific’s Jupiter and Union Pacific’s No. 119 — two massive 30 ton locomotives — met to complete the transcontinental line. Chinese workers — 90% of the labor force in the mountains — were excluded from the golden spike photo and ceremony broadcast across the nation.

That photo-op at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10th, 1869 was centered around tapping in that final railroad spike, kind of like the final nail in a coffin or a door. Once that spike was in place—the golden spike—then the continent was connected by the advanced tech of the day.

The physical railway that allowed for the transportation of goods and people was one advanced tech, but it wasn’t the only one represented by the tapping in of the golden spike. The information railway was equally important, and it wasn’t just represented metaphorically by the completion of the railway.

When the final spike was tapped in, something akin to the first ever national broadcast happened somewhat automatically. It was all very performative: the spike was solid gold, so it wasn’t any good for keeping the rails in place and would be replaced with an actual iron nail. And, there were wires attached to both the hammer and to the rail itself, so when the hammer tapped that final nail in Morse code, the single word “DONE” traveled to both San Francisco and New York.

What a moment! What a commemorative performance. What a sad moment not to include any of the labor in the commemoration, too.

Actually, the hammer operator didn’t really spell out the word “DONE”, but instead just tapped the spike in. An actual telegraph operator received that signal, and that’s who typed the word “DONE” and sent it off to both coasts, broadcast style.

Now, don’t get me wrong—there was already a telegraph line that went from coast to coast, but the people building the railroads saw that the world around them was fundamentally changing, and they wanted to commemorate that rapid change, best represented by the telegraph and the railroads.

This was a compression of both space and time, and it was represented by a single spike in an incredibly long railway line.

In our history, there have been a few similar moments where a new technical paradigm was loudly announced onto the world stage. The Mother of All Demos comes to mind immediately, where in 1968 Douglas Engelbart introduced the idea of sharing a screen with someone in another city, the computer mouse, emails, word processing programs, and spreadsheets.

Everything was just ready all at once, gradually then suddenly. It’s not quite like the golden spike moment, though: the internet would take another three decades to gain widespread recognition, while railroads and telegraphs were already widely understood as important.

No other revolutions or innovations quite fit the gravitas of the golden spike moment, but I think one person came the closest: Steve Jobs. In his killer Apple demos, he was able to showcase a new technological paradigm and announce to the world why it was important. Was the iPhone demo more like the golden spike moment than the Mother of All Demos, or is there another golden spike moment you can think of that fits in better here?

We need to do that again with high speed rails.

Canada's main railroad, the CPR, was built around the same time as the American transcontinental railroads, using the same kind of methods and the same kind of ethnic workers. It had a Last Spike ceremony at Craigellachie, Alberta, with the spike being driven by Donald Smith (a.k.a. Lord Strathcona), one of the businessmen who had provide necessary funding for the project.