At the start of the 20th century, the scientific world was buzzing with ideas about animal intelligence. Darwin’s Theory of Evolution had given a fresh perspective on whether humans were the only ones to have certain attributes, and intelligence was one of these traits that seemed to be on a sliding scale.

American psychologist Edward Thorndike’s recent experiments with cats escaping various puzzle-boxes showed that animals could find a solution to a problem through trial and error, then repeat that solution later on. Meanwhile, Pavlov’s recent work studying dogs showed that animals could form new associations, like when dogs salivated at the sound of a ringing bell in anticipation of food.

The overall vibe was that we were discovering all sorts of things we didn’t know, like the phenomenon of radioactive decay, or the ability to broadcast a radio signal across the world. Anything seemed possible, and animal intelligence was one prominent area of study.

That’s why it didn’t sound all that crazy when a retired German teacher started making claims that his horse could read and understand German, tell time, and even do basic math.

After retiring from teaching math for decades, Wilhelm von Osten dedicated his life to the study of animal intelligence. He was an avid amateur horse trainer, and he thought he had an exceptionally intelligent horse named Hans on his hands.

To demonstrate Hans’s abilities to the world, von Osten devised a presentation designed to showcase just how smart Hans was. The demo would begin with someone presenting Hans with a math problem, like “What’s 2 + 2?”

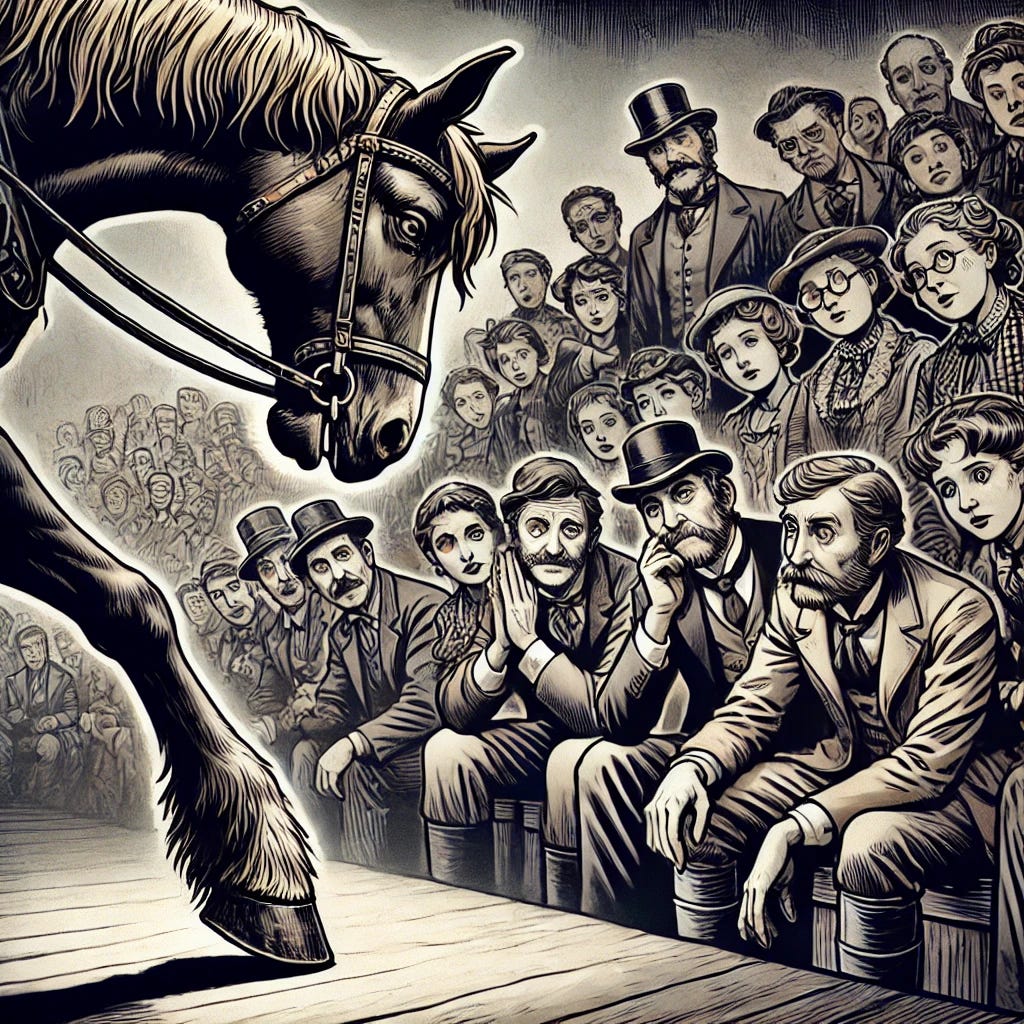

Hans would then tap his hoof on the ground, “counting” up until he got to the correct answer. Then, Hans would stop tapping. To the astonished onlookers, this seemed like irrefutable proof that a non-human animal could learn math and think logically.

This was no scam, though. Hans the Horse really did stop tapping at the right answer, and von Osten really did think he was a genius.

What was going on isn’t quite as fascinating as learning that animals can do math, but maybe it’s even more interesting due to what it reveals about us.

Naturally, there was a desire to test Hans’s abilities in a more scientific manner, and von Osten eagerly agreed. A renowned German psychologist named Oskar Pfungst used the modern scientific method to devise a series of tests that would carefully measure one variable at a time.

Pfungst’s tests revealed that two conditions had to be present in order for Hans to provide the correct answer. First, the humans asking the question had to know the answer. Second, Hans had to see the person asking the question.

If von Osten didn’t know this was a scam, though, how could the trick work?

Here’s where human psychology comes into play and makes things really interesting for us. Both Hans and the audience were participating in a kind of unintentional kayfabe, where performers and audience are in on the act.

Hans would start tapping the answer, then pick up on subtle cues from the audience or from the person asking the question. Every crowd would hold their breath in anticipation of Hans’s brilliant demonstration, and in doing so, they gave off little signals to Hans.

When Hans got to the right answer, the crowd (or questioner) would relax, letting Hans know the answer was approaching. He would stop tapping when he got this signal.

Hans wasn’t really a super-genius horse, but learning through the lens of cases like Hans’s can be incredibly helpful. Intelligence is something we’re only beginning to understand about ourselves, and the world of biology reminds us of how much more there is to learn.

Are you telling me that the 60s sitcom "Mr. Ed" was a ruse? Say it ain't so!

My brother’s name is Hans and he isn’t a super genius either.