How to Know Things

During the 1950s, scientists took on an almost mythical aura.

The atomic bomb had just exploded onto the world stage in the biggest way imaginable, marking the conclusion of the deadliest conflict in human history. It wasn’t the jocks, but instead the scientists who won the war for the west.

If this feels overly simplistic, that’s fair. The atomic bomb probably wasn’t decisive, and it certainly wasn’t what ended the Nazi occupation of Europe. Still, it was technology driven by discovery that fueled this incredible innovation. It was a perfect blend of science with industrial capacity.

These wizards became gods of the modern world in some ways. Sure, these were the eggheads; the geeks; the nerds. Nevertheless, the mythos of the scientist as some kind of elevated mind, quite apart from the rest of humanity, persists even today.

The funny thing is that science is the perfect tool for anyone trying to make a decision, not just nerd-gods in lab coats.

The funnier thing is that science is almost a dirty word, but it really just means knowing things. Depending on what sort of worldview you ascribe to, you might point out that knowledge has a history of being perceived as dirty or dangerous, so maybe science ought to sound a little dirty to us. We can agree to disagree here. I think knowing things is really cool, and I want to know way more things.

If you, too, wish to know more things, there’s a particular technique I’ve found to be far more effective than any other way of finding out whether something is true or not. It’s often called the scientific method, but I want to talk about what that really means today.

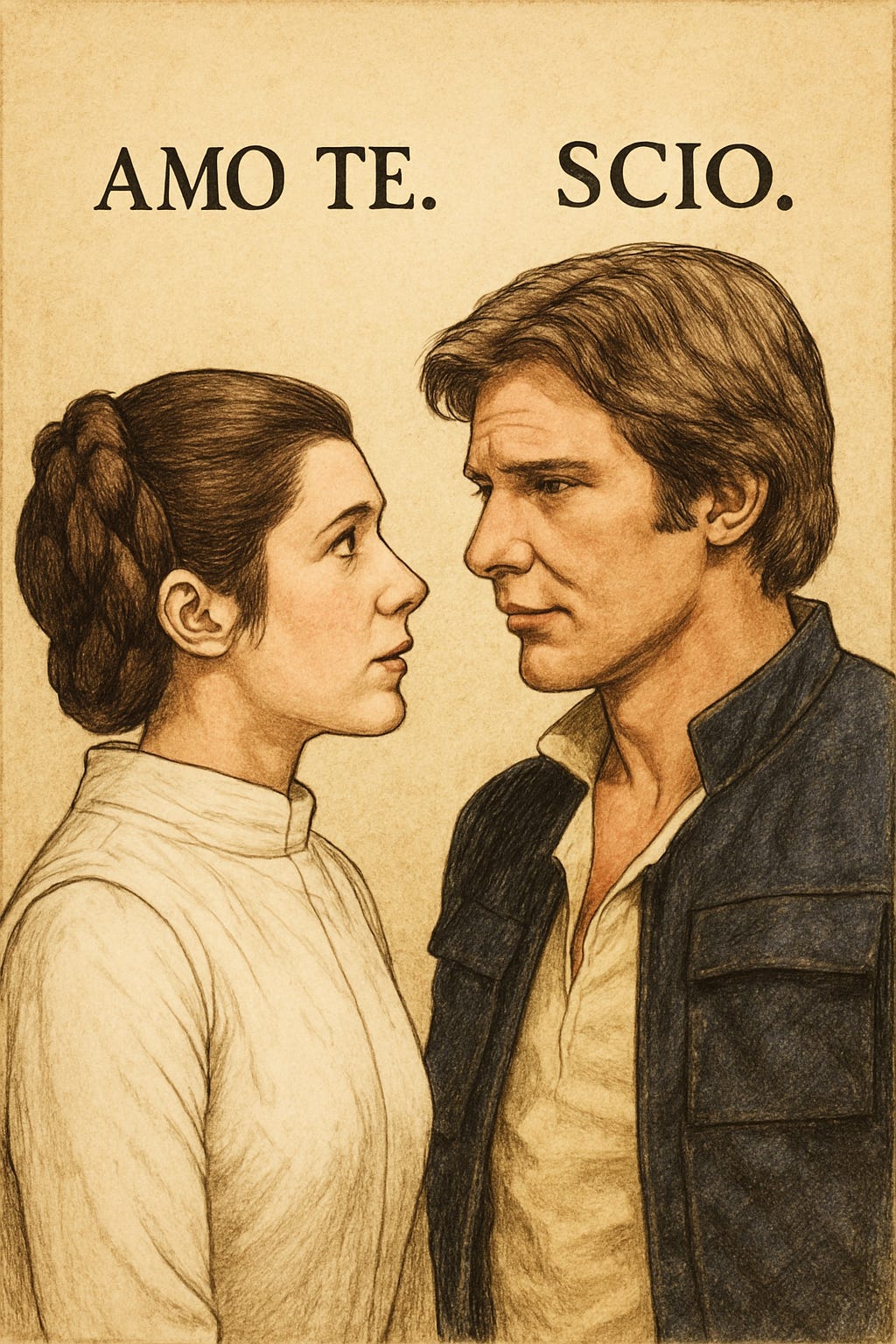

As usual, the etymology tells its own story. If you were a Roman and you said, “Scio,” you were saying “I know.” The Proto-Indo-European root word, something like _skei-, meant to cut something, which gradually became a metaphor for all types of splitting and sorting.

Sorting through things sounds boring, but it is also the very basis for thinking. Without sorting, information is just overwhelming, flooding into your brain nonstop:

These sensory inputs are very evidently a form of raw data coming in, which our brains then sort into useful, actionable information. Sometimes you can have too much information coming in all at once, like when you bite into something that has too many flavors all at once, or if punk rock music just sounds like a cacophony to you.

With a little sorting, though, you can figure out what it all means.

By the time of Shakespeare, science meant any type of organized knowledge, not the more narrow band of physics, chemistry, and biology we typically consider scientific today. Gradually, the word scientist came to mean paid professionals working on these more narrow fields, but it wasn’t overnight.

The scientific method, at its core, is really just about how to know things. It needs a rebranding—maybe we can just call it the way to know things.

You start by being curious about literally anything. You then need to ask a clear question, like why is this octopus drunk? Next, you make a guess as to why.

You guess?

You’re thinking: guessing sounds like the very opposite of science. I’m saying: sure, if that’s all we do, but we don’t stop at guessing. Instead, we test whether the guess is correct or not.

In fact, we try very hard to disprove the idea. We throw everything we can think of at the idea, falling deeply out of love with our genius creation for long enough to try and prove that it’s wrong. This is not how you typically treat cherished things—by trying to prove they shouldn’t be! Yet, this is the way.

I’m going to let Feynman bring this one home:

If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong, and that’s all there is to it.

That’s true of all facts, whether or not these experiments take place in a lab full of beakers. The trick lies in asking the right questions and in faithfully testing them out. No cherry-picking allowed!

Today’s little ditty comes to you by way of a radio program I heard on NPR not long ago. Yes, that kind of radio.

A deeply fundamentalist religious woman determined that she would go off to college, and use education to prove that evolutionary biology was wrong. In her quest to disprove Darwin’s theory once and for all, she eventually figured out that the theory actually makes perfect sense.

The more she dug in, the more clear the picture got. Now, she is herself an evolutionary biologist.

Science is about knowing things, whether or not they happen in labs.

I have to think that the MAGA people who demonize scientists worst now grew up in the time when they were lionized, and that this is a way of rebelling against people with "knowledge" they do not have who rub the "knowledge" in their face.

But anti-intellectualism existed in America long before then; it almost seems like a spectator sport sometimes.