I happen to know that James Clerk Maxwell was 48 years old when he died.

In that relatively short lifespan, Maxwell contributed as much to our understanding of the universe as almost anyone else, ever. When asked if he stood on the shoulders of Newton, Einstein said no, “I stood on the shoulders of Maxwell.”

He meant it, too: relativity came to be thanks to Maxwell’s foundational work with electromagnetism. Even beyond that, virtually all modern physics—both relativity and quantum mechanics—is built on Maxwell’s ideas and discoveries.

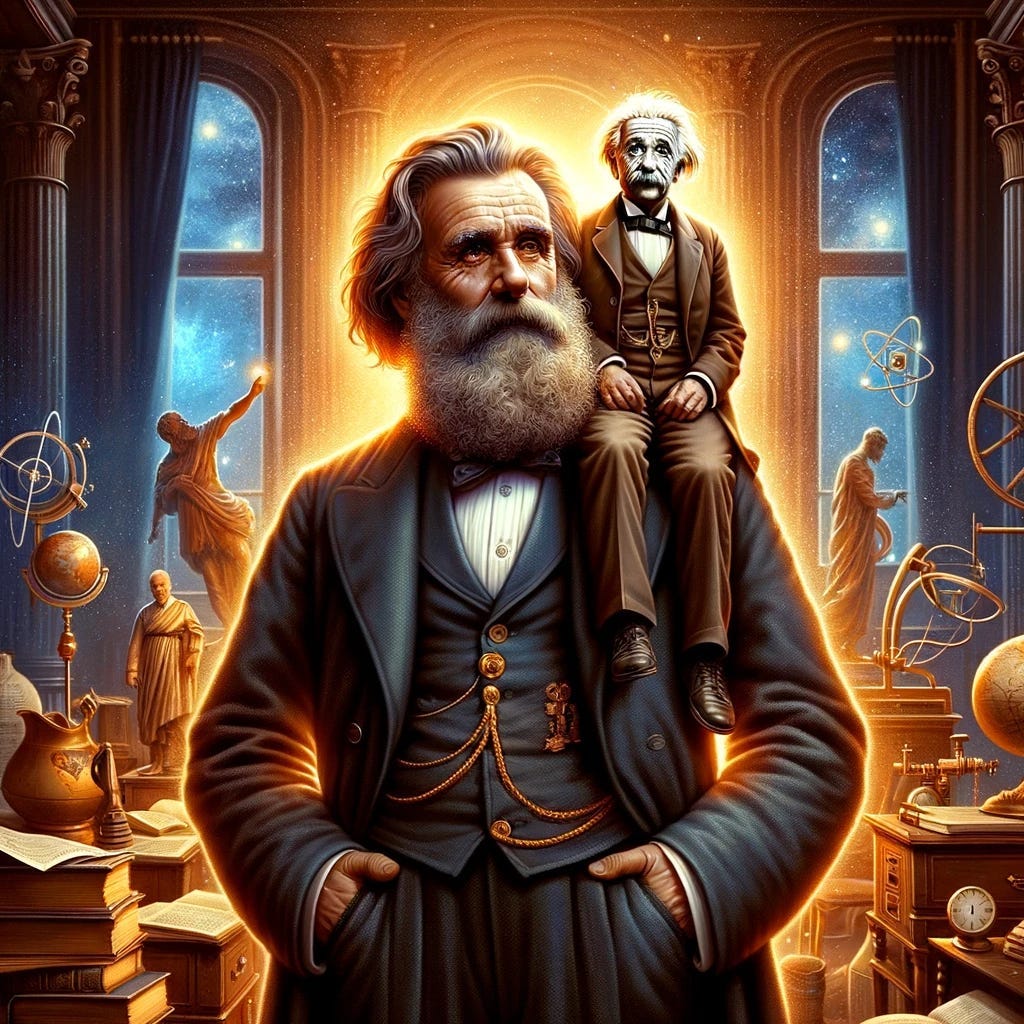

Like Einstein, Maxwell enjoyed a good thought experiment. These little games envisioned things that were difficult or impossible to set up in an actual experiment, but if you imagined what would happen if they played out, you could sometimes come to understand nature better.

One of these thought experiments came to be called Maxwell’s Demon.

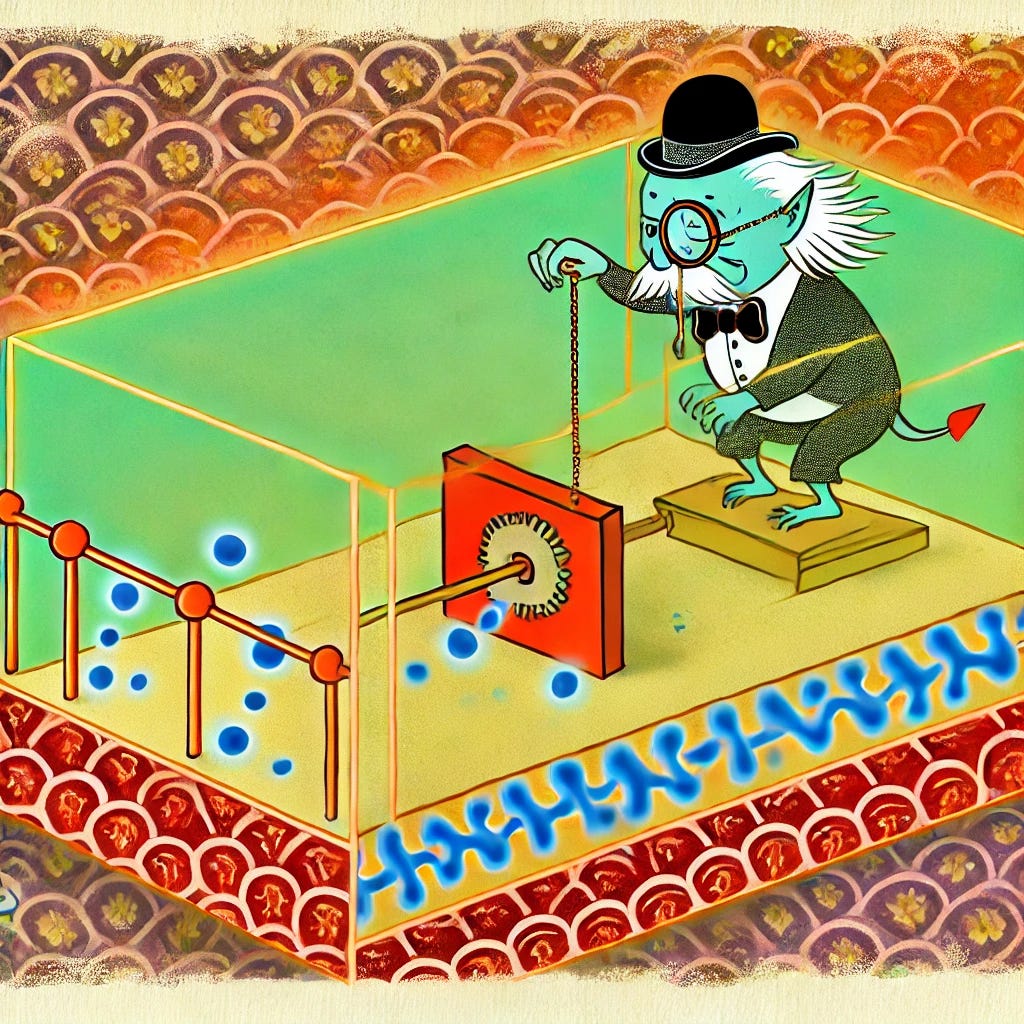

You start with a box full of a gas. It’s not really too important what kind of gas is in there, but what matters is that there are lots of atoms in there, flying around all over the box. It seems to be a frenzy of random activity upon first glance.

After you observe the box carefully for a few minutes, though, you begin to notice that some of the atoms are flying around really quickly, while others are moving very slowly by comparison. This gives you an idea.

You’ll make a little wall right there in the middle of this box, dividing the right side from the left. Then, you’ll place a tiny door there that can be opened or closed at just the right time. This little portal can allow one atom at a time to slip through the wall, over to the other side of the box.

The idea you have is to let only the cold atoms to enter over on the right side, while only the hotter ones stay on the left side. After a while, you would start to see stragglers—fast particles on the right or slowpokes on the left. Each time you get the chance, when one of those particles is about to hit your wall in the middle, you just open that tiny portal.

Only, Maxwell knew that you couldn’t really do this, so he invoked a tiny supernatural creature he called his demon to do his dirty work. His demon would make sure that the right side had only cold particles, and the left side had only hot particles. One way to interpret this was that you could just capture heat from anywhere in the universe, isolating into a small area and using it whenever you needed to.

A free lunch, if you will.

This demon could conjure up “free energy” where there didn’t seem to be any, and this seemed…. well, wrong. It was anathema to the way things worked. There’s no crying in baseball, and there are no free lunches in physics.

Here’s how I described the second law of thermodynamics, which this little demon seems to violate:

The second law describes entropy, a measure of the amount of disorder in a system. The short explanation here is that there are vastly more disordered states than ordered states in nature, and hot movements—sorry, hot dynamics—ultimately cause the proverbial dice to roll over and over again, ending up with more disorder than order.

What’s going on here? As far as I can tell, there are no perpetual motion machines out there, just grabbing energy from the air forever. Why doesn’t Maxwell’s Demon actually work?

It helps to remember what those hotter, faster moving particles really are. They are in a higher state of energy, and what you’re trying to do is concentrate that higher energy in one spot. On the surface, it might seem as though this is just fine—after all, it’s the same amount of energy inside the box, right?

Well… kind of. This is exactly where things get really, truly interesting.

It turns out that it costs energy to separate those particles. I’m not talking about whatever energy it takes to open and shut Maxwell’s Demon’s little trap door, but instead a different type of energy. This is the energy required to sort anything out, or to think about something.

Maxwell’s thought experiment implies something fundamental about the universe that the modern thinkers are still trying to get their heads around. It’s the idea that information and energy are much more deeply intertwined than anyone had previously dared to imagine.

Specifically: information has a cost in terms of energy.

There’s really no free lunch here, since it costs just as much energy to steal organization from the universe. The universe is in a state of constantly becoming more and more disordered, and that means organization gradually erodes as a rule.

Think about what the demon has to do in order to sort the particles. First, it needs to determine the speeds of the particles flying around in the first place. Then, a decision has to be made about how to sort each particle; and finally, the pieces can be actually sorted (the door can be made to open or close). Every one of these steps costs actual physical energy.

Even if you replace the demon with a device, it makes no difference. All that measuring and sorting still has to take place, so it still burns up energy.

20th century physicists took this thought experiment and ran with it. Gradually, a theory of the way things work called It From Bit arose to address the demon and its inevitable conclusions. Some interpretations of this theory suggest that the fundamental building block of the universe isn’t energy, but information.

It From Bit is an active field of study among physicists today, right at the forefront of cosmology. Besides physics, we’ve seen this link between energy and information play out more directly and tangibly here on planet Earth, as Large Language Models and other AI systems gobble up ever-increasing amounts of energy.

Information has a cost, and that cost can be measured in terms of energy.

Maxwell let an actual Demon into the box? So that's who murdered Schrodinger's Cat!

Mystery solved!

Measuring and sorting involves judgement, which may be another term for dualism. As long as we approach the issue from this perspective, we have an unsolvable, perhaps…