Thought Experiments

You start out without experience in the physical world from day one. All you can compare this new experience to is what you went through in the womb, but everything out here is brand new to you.

Physical experiences teach you a lot about how the world works. You understand things like discomfort and hunger right away thanks to hormones and DNA, but beyond this sort of hedonism, there’s not a ton of cognition just yet.

After a few years of testing the boundaries, you now have a great deal of data from the world, and you can start to draw some conclusions about how it works. Baby powder going in front of a fan creates a delightful snowstorm of tiny particles, you notice one day. Water flows like so, things stay hot for a while if they’re made of certain materials, and so on.

At some point, however, your imagination starts to outstrip your physical surroundings. This is a magical moment when you can begin to think about things that aren’t real, contemplating not only what is, but what isn’t and what might be.

It’s the what might be category of this childlike imagination that gives us the thought experiment. By deducing the outcome of one of these practical fantasies, you can get an idea of what’s really going to happen out there in the world.

This has the huge advantage of you not needing to gather materials and resources for a physical experiment, so you can save loads of time and energy. But there’s something even more notable about this concept: you can run experiments in your head that you simply can’t run in the real world.

Zeno’s paradox is one of the great ancient thought experiments. Achilles won’t ever catch the turtle, according to Zeno:

Zeno describes a footrace between Achilles and a tortoise. In order to give the tortoise a sporting chance, the greatest of all Greek warriors allowed him to start at the halfway point between the start and finish of the race.

Zeno observes that by the time Achilles gets up to that point where the tortoise started, the tortoise will have moved forward at least some. That means our hero needs to get up to where the tortoise is now, and of course by the time he gets there, our reptilian adversary has once again eked ahead by some small margin.

Two areas where thought experiments like these come in really handy are infinities and infinitesimals. You can’t physically gather an infinite number of things for a physical experiment, and likewise you can’t cut something in half forever in the real world.

One outcome from this particular thought experiment was the eventual invention of calculus. The idea might be just to stretch your mind a bit, but there is often a practical outcome from thinking about things that you can’t do in the physical realm.

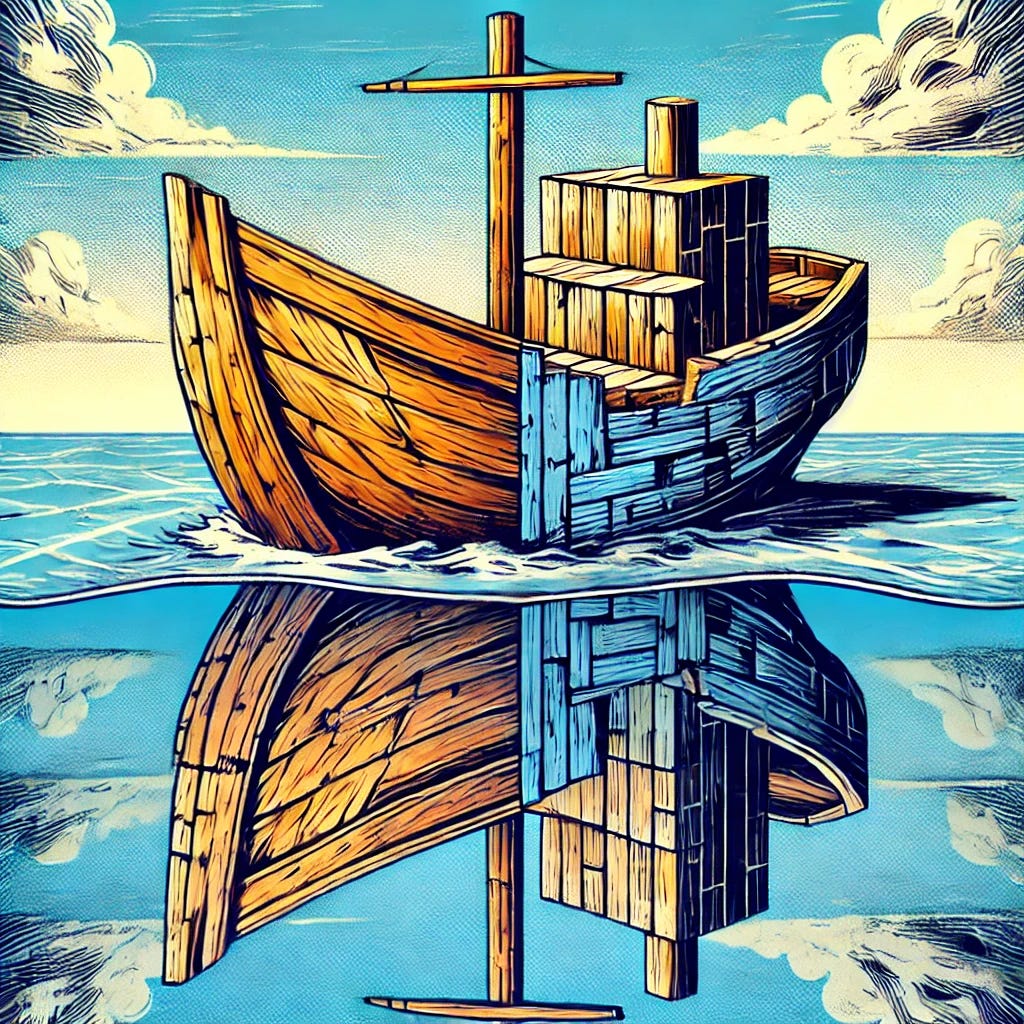

Another ancient thought experiment is called the Ship of Theseus, which I’ve described like this:

Imagine, if you will, a ship that has weathered many storms and battles. Over time, its wooden planks become worn and rotted, requiring replacement. Slowly but surely, every single piece of the ship is replaced, from the boards of the hull to the towering mast.

Now, suppose that someone were to collect all the original parts that were replaced and use them to construct a new ship. The question then arises: Which of these ships is the true Ship of Theseus? Is it the one that has been meticulously restored, each piece replaced to maintain its function and appearance? Or is it the one assembled from the original parts that once made up the famous vessel?

This one speaks to me deeply about identity. I know that our atoms replace themselves during our lifetimes, and most of our human cells do, too. We’re not made of the same stuff as when we’re born.

Language is another area where Theseus really connects with me across the millennia. Do a billion people still speak Latin today? I make this case here.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave is yet another ancient thought experiment that produced incredible results that we humans all benefit from today. When the prisoner escapes the dark cave and goes out into the world, he finally understands that what he thought was reality wasn’t so. Of course, the other prisoners think he’s gone crazy.

Every bold new idea sounds crazy at first, and Plato reminds us that ostracism is part and parcel with the territory. He also makes us consider that what we see isn’t necessarily what we get, and the menu isn’t the same as the meal.

These ancient thinkers gave modern physicists and philosophers an incredible and valuable tool, and these modern thinkers have run with it. Most famously, Einstein’s gedankenexperiments dealing with light and gravity have utterly shaken our perceptions of the way everything works.

Just by thinking about these things in the right way, Einstein was able to show that there’s no such thing as “at the same time” unless two things touch. This led to the idea that time wasn’t some kind of constant thing, but instead something that could be stretched or compressed, just like space. Eventually, Einstein realized that space and time were the same thing.

Philosophers, too, use thought experiments to contemplate some of the thorniest issues in our modern world. The Trolley Problem introduces the following conundrum:

A runaway trolley hurtles towards five workers who are completely oblivious to the certain death they face, as the trolley is destined to turn them into a smear on the tracks in just a few seconds.

You can pull a switch that will divert the trolley onto the track that runs away from the workers, but there's another worker there, too. Do you pull the switch and consciously choose to kill one to save five, or do you do nothing and let the trolley take its course, killing five but sparing the one?

The analog with self-driving cars is far too good to ignore here, as I explored in Driving Over Miss Daisy. These are no longer abstract questions, but instead directives to program into a car. These are real decisions that will have to be made.

My own thought experiments always tend to gravitate toward physics, where things are as big (or small) as they can get, as fast (or as slow) as you can imagine, and the extremes are the norm.

I run a little thought experiment every night right before I fall asleep, and sometimes I really do draw some interesting insights from the exercise. Other times, I just fall asleep. Either way, it’s a win for me.

In Driving to the Moon, I imagined how long such a silly venture would take if I was driving at highway speeds. I pointed out that I had, in fact, driven the distance to the moon with a car I owned, and back with other cars. Connecting these two realms—the cosmic and the earthly—is what led Newton to his universal theory of gravitation.

Personalizing the Passage of Time gave me an opportunity to put deep time into a personal context, envisioning my own lifetime as compared to centuries past. By comparing my own world to the rest of the universe, I can make sense of things by connecting them in this way.

Now, let me turn this over to you: have you run your own little thought experiments? Did you learn from them, or do you just use them to fall asleep at night like me?

Oh yes, thank you for asking.

I spent many years playing music, mostly singing but some of the time I played the flute. After a particular solo, I had only so much time to turn, step back a few , set the flute on its stand, and be back to the microphone in order to sing again. If I just tried to do it, I couldn't. There wasn't enough time. But I was able to count, effectively dividing the interval up into eight segments. And in each one of those segments was able to visualize moving a certain distance. If I counted, I could consciously stretch the time between the moment I left the microphone and the moment I returned to it. As a matter of fact I have myself on videotape doing this, but you can't see me counting.

I did something similar while running, as a child. I think it was when I was a child that it occurred to me that time existed mostly in my mind, and could be stretched like silly putty, if one only knows how to do it. Not very scientific but, there it is.

Your column made me think of that song. I love that song!