I know a thing or two about Smiths.

Most of my life, that knowledge has been concentrated on people with the same last name as me. If you share my last name and we also share some DNA, I probably know at least a tiny bit about you.

Lately, my Smithopedic knowledge has extended into the realm of etymology. Common words can become names, so diving into the origins of my own last name makes a great deal of sense.

Go back far enough, and you reach Old English, where Smith was an occupation instead of a name. The word smið sounds very close to today’s Smith, with the -th sound being a bit softer back then.

A thousand years ago, these smiths were an incredibly important part of the community. Actually, important might not be a strong enough word.

First and foremost, smiths were creators. They took raw materials like iron, copper, wood, and stone, and turned them into the objects people needed to survive.

Defense was paramount, and smiths were the ones responsible for making weapons like swords and axes. If there was armor needed for a battle, it was the smiths you would turn to. Suffice it to say: if you wanted to kill someone or prevent someone from being killed, you were going to need a smith.

Some smiths could make ornate, beautiful objects. These creators were adored by their fellow residents, almost promethean in nature—they stole a clever idea from the gods, and they worked around intense heat and fire. They seemed almost supernatural in many ways.

As essential as defense was, smiths were responsible for a whole lot more of the important, everyday tools people used. Metal sickles made field work considerably more efficient, and nails fastened together furniture and even houses. If you wanted a door that opened and closed, you probably wanted metal hinges, and maybe even a metal lock.

Bits, stirrups, and eventual shoes (horseshoes were not common until later in the period) equipped horses. Smiths made pots and pans from wrought iron, and you can bet that you would rely on the smith if your only big pot had a crack in it.

For these reasons, smiths were central to the community, and their smithies—their places of work—frequently became social gathering hubs for the entire village. Hanging out with the smith might be a bit like hanging out at the coffee shop centuries later, where ideas could be exchanged and information could spread.

Last names, as I mentioned, weren’t always names. If I was named Andrew, there might be several different ways to identify me, including who my father was. If my dad’s name was Sam, I might be Andrew Samson (or, as my brilliant calculus teacher called me, “Son of Sam”).

If I was a smith, though? You might just start calling me Andrew Smith. I’d be okay with that, I guess.

My own family history reinforces the idea that there’s something to the name. I come from a long line of Sam Smiths, many of whom seem to have been builders of some kind. My dad worked with me to create wooden toys we could sell, and prior to that, he built his own furniture to sell as a business when he wasn’t teaching (or, possibly, to escape teaching).

His dad, Sam Smith, worked briefly on the Manhattan Project, but not as a physicist. Instead, Sam was a carpenter who worked to build a facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee that would ultimately enrich uranium for the first atomic bombs. Sam also built houses for a living in his home town, and he would sometimes quip that he had built the house for every rich person in town, or something to that effect.

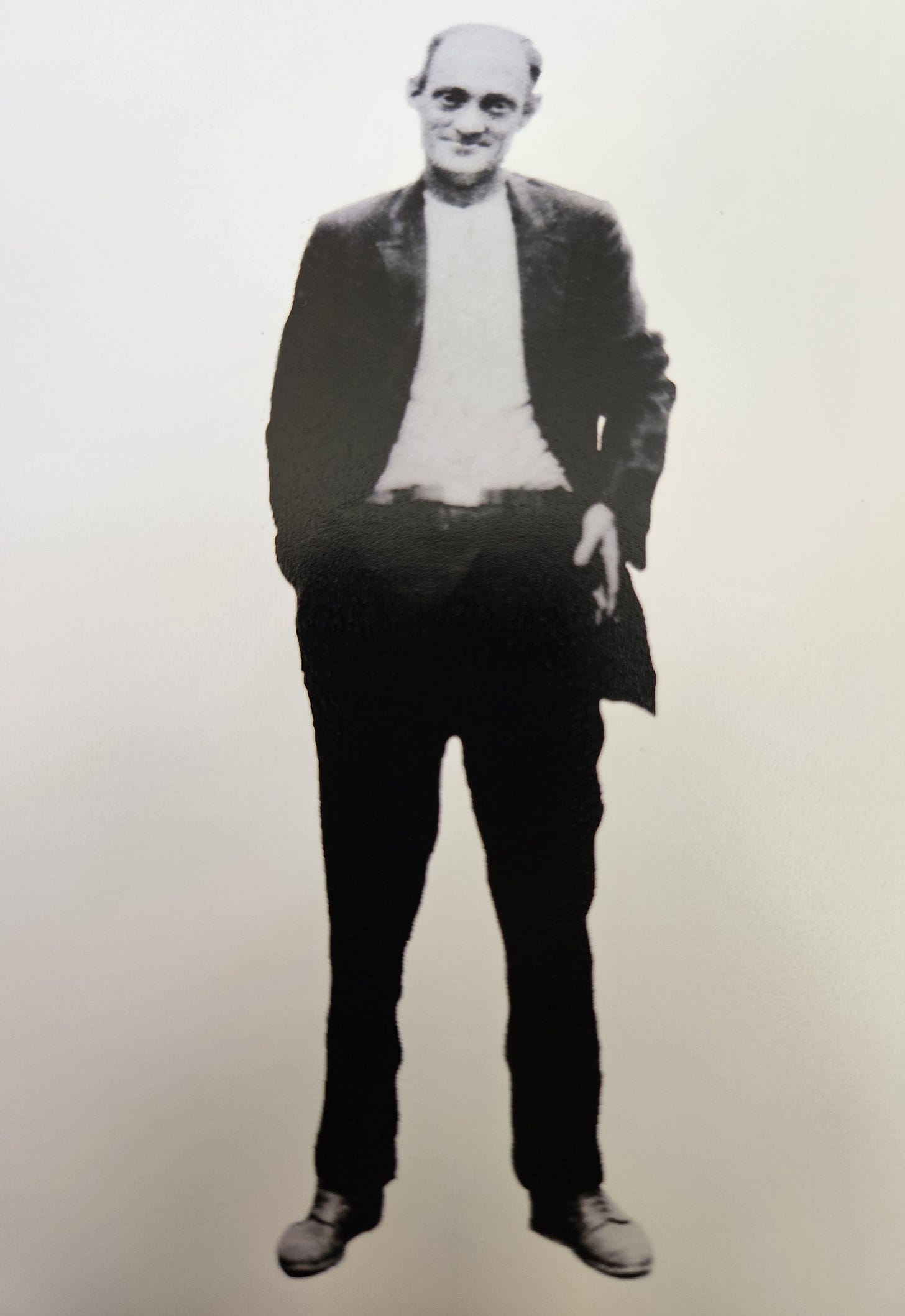

His father—my great-grandfather—was also named Sam Smith, and he was also a carpenter. Here is the only surviving photograph of him I know of:

There’s a family quote that’s supposed to be about him that I have jotted down:

He could saw boards all day, even though he had only one lung. But at night he was too tired to do any of the housework.

This Sam died in 1931, just as my grandfather was hitting puberty. This ultimately triggered my grandfather to be orphaned around the same age that I started complaining about a rough middle school experience.

As a result of his father’s abrupt death, my grandfather Sam participated in his first building project, “to build a concrete curbing around his burial place at First Presbyterian Church in Clover, SC."

One more quote survives about the legend of the Smiths in this family:

On your first birthday, a Bible and a hammer were placed in front of you. If you went for the Bible, then you were going to be a preacher. If you went for the hammer, then you were going to be a carpenter.

I think about this quote (attributed to my grandfather) a lot. My own life has sent me in pursuit of both the carpenter aspect and the preacher aspect, but I don’t really view it as such a binary thing. What I mean is that I don’t build houses, per se, but I have always enjoyed creating things, and I’ve had a very high bandwidth for it my entire life.

At the same time, I am not a preacher, but I do tend to communicate quite a bit with other people. I put a message out there, so to speak, and this desire to connect with others on an intellectual level is every bit as important as the creative aspect.

It is this very dualism that I once tried to joke with Lou Ferrigno about, but Lou wasn’t having it.

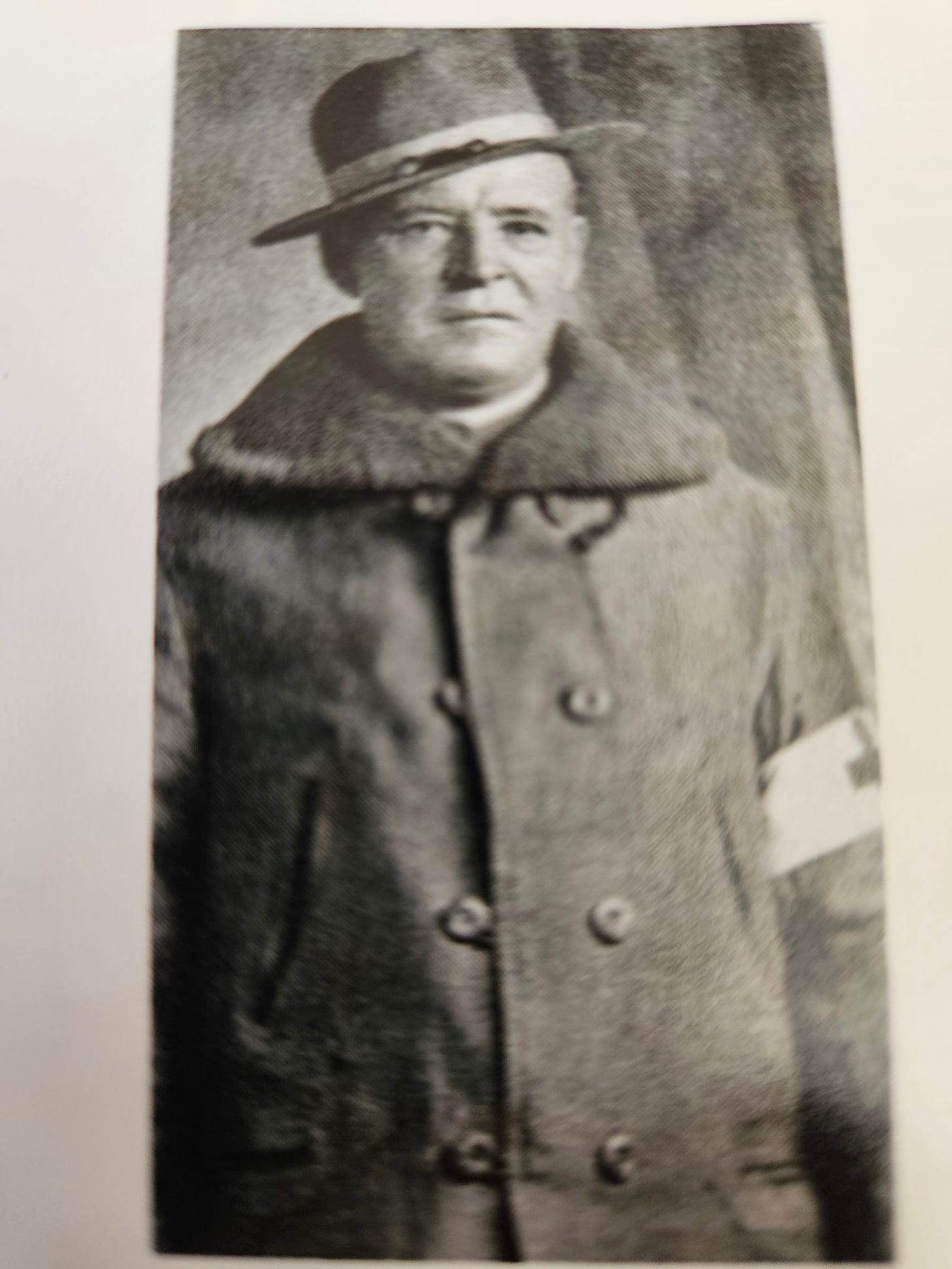

Yet another Sam Smith, one-lung-Sam’s father, was a medic during the American Civil War. Incredibly, this photo of him survives:

I will have an awful lot more to say about these Smiths.

My wife's family tree has a Smith and a Smith who got married, but it got weird because that Smith's parents were Smythe. It looks like they changed their name from German to English during WWI.

Thanks for sharing a bit of your family background. Depending on how you feel about it, there are some AI tools that would let you colorize and otherwise bring these old photographs to life. Or maybe they're best left exactly as is.

Also:

"On your first birthday, a Bible and a hammer were placed in front of you. If you went for the Bible, then you were going to be a preacher. If you went for the hammer, then you were going to be a carpenter."

Jesus: Why not both?!