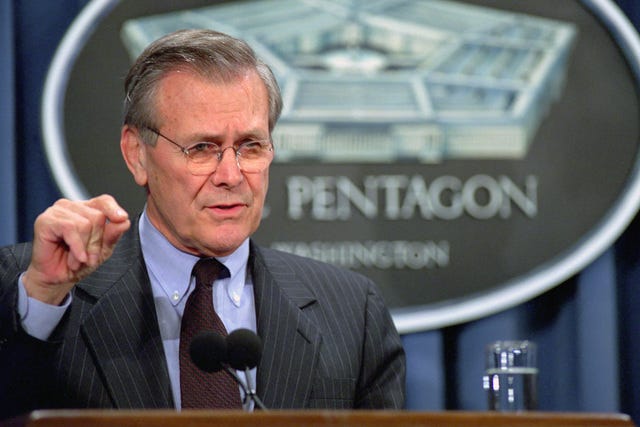

Donald Rumsfeld, both the youngest and the oldest US secretary of defense, famously laid out a framework for thinking and decision-making.

The Rumsfeld Matrix, as it has come to be called, consists of these four broad categories:

Known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns, and unknown knowns.

That probably sounds like jargon, but we can break it down pretty intuitively, to see how the framework can be useful.

Known knowns are those things that we know that we know (huh?). That means we are aware that we know something, like we know that light travels at a fixed velocity, no matter the observer. We know how scorpions have sex. We know fungi can form an internet of sorts.

These are the little facts we collect for trivia night at the bar, but also things we need to know for a job. We might put these skills on our resume if we were applying for a job.

Known unknowns, by contrast, are things we know that we don’t know about. Now, it might be useful at this point to mention that known is doing far too much heavy lifting here.

In this matrix, the known or unknown on the left (the first word) lets us know whether or not we possess the collection of information on the right. Rumsfeld mainly wanted to leverage the power of alliteration when he used the word known to describe both types of information, but it might be helpful to think of the left hand terms as binary, either true or false.

The term on the right can be a specific number, or anything, really. The known unknowns are fun to think about, and I’ve written about them a ton. We know that we don’t know whether there is a theory of everything that describes how the universe works. We know that we don’t know when Moore’s Law will officially end.

Unknown unknowns are all the things we don’t know that we don’t know. We’re not even thinking about how to look for these things, since we don’t know they exist, and it has never occurred to us even to consider that they might.

One good example of this is from particle physics during the middle of the 20th century. Physicist I. I. Rabi famously quipped, Who ordered that?!? when his team discovered the muon, a particle just like the electron, but much heavier. Decades later, Murray Gell-Mann used this clue to piece together the standard model of particle physics, completely revolutionizing the field on the basis of that discovery.

Finally, we come to the unknown knowns. This category often flies under the radar, as everyone zeroes in on the unknown unknowns—our instinct to avoid uncertainty at all costs is front-and-center here, fearing something we might not even be able to imagine.

By contrast, the unknown knowns can be surprisingly positive. After all, we’re discovering that we actually know how to do something, or how to think about something. We have this untapped skill we didn’t even know about.

I see this in jiu jitsu all the time. Students at our gyms are humble, and that’s a very good thing! However, this humility often keeps them from understanding that they actually know more than they think they know. “Oh, I guess I do know how to do that armbar,” they might say.

In fact, this happens to me from time to time. Someone asks me if I’ve seen a move before, and I’ll say that I haven’t. Then, I might practice the move once and realize that I not only saw it like 25 years ago, but I’ve actually hit it live while rolling several times over the years.

If someone tries to grab me, I’m unconsciously already defending whatever it is that they’re doing, seeking to optimize my own leverage in an instant. My body starts reacting in a reasonably intelligent way long before my brain can get involved with any sort of higher level cognitive process.

Have you ever listened to your gut? Sometimes, your body intuitively knows something your brain hasn’t quite figured out just yet. It might be that a particular activity is more dangerous than it first appears, or maybe your gut is telling you to go for it.

Similarly, we recognize faces in an instant, but if you asked someone what features they saw or how they did it, we’d be hard-pressed to come up with a sensible answer. In many ways, your subconscious mind (and your gut) are your superpower.

Your gut can be wrong, though. You have to be careful not to fall into the trap of inherent biases, and it’s up to each of us to figure out the right balance between listening to intuition and listening to reason.

I tend to lean in toward the reason aspect really heavily, but I recognize that there are these unknown knowns out there, and we don’t fully understand intuition.

Does this framework help you out any? Do you already use this type of thinking? Are there any unknown knowns from your own life you’ve discovered?

I am probably confusing those four rules with another four rule mantra. I heard about four processes involving our movement from newbie to master, but not sure if I remember the words correctly:

Subconscious incompetence - we don’t think about the action we can’t do - unknown unknown

Conscious incompetence -we think about the action but we can’t do it - known unknown

conscious competence - we have to think about the action in order to do it - known known

Subconscious competence - we don’t think about the action in order to do it - unknown known

You mentioned it in your body knowing how to react to stimulus before you’ve thought about what to do.

This has always seemed like gobbledegook word salad but now that you explain it, the unknown unknows are what get us every time. If only we knew, then truth could be just as strange as fiction.