Theory of Mind!

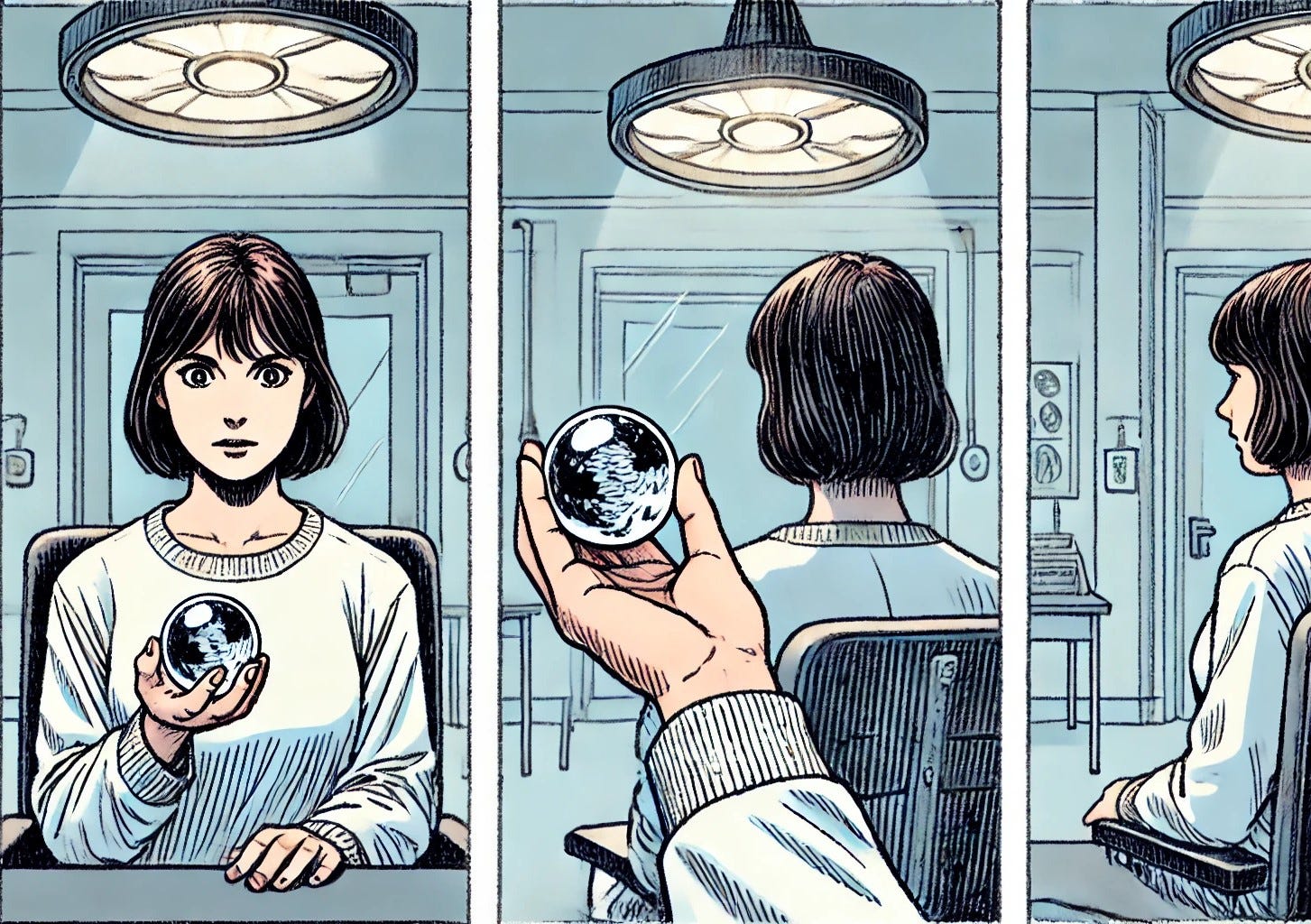

Sally is in one of those controlled settings that psychological experiments will often use. Sally holds up an intriguing object and turns it around in her hands. She hides the marble in a basket, then leaves the room.

Next, Anne comes in and sees the marble, grabs it, and moves it over to a box instead, where it seems like it belongs. Anne leaves, and Sally returns to get her marble.

The question asked to the kid observing on the other side of this two-way mirror is: where will Sally look for the marble? The way the kids answer can tell you a lot about what’s cooking upstairs.

If a child is four years old, there’s a good chance they’ll say that Sally will look in the basket, which is where she left it. She believes the marble is in that basket. This would make logical sense to any of us.

If the child is three or younger, though, there’s a much better chance that they’ll say that Sally will look for the marble in the box. That’s the last place they saw it, so they reason that everyone else in the world thinks exactly the same way as them.

This seems pretty silly, but it’s a great illustration of a concept psychologists call Theory of Mind. In the classic Sally-Anne task experiment, it is the understanding of a young child that we study, but the lessons apply every bit as much to us so-called grown-ups.

The concept of empathy is a lot like an emotional version of Theory of Mind, and it goes back thousands of years. Putting yourself into someone else’s shoes is a useful trait if you want to understand how someone else might feel about a given situation.

ToM uses a structured approach to the cognitive version of seeing things as another person sees them. If you’re working the night shift with someone and you ask them if they want to sweep or mop, and they tell you that your mother smells of elderberries, there are a few different ways you can respond. One way would be to insist on a fight right then and there, based on the egregious insult.

Another way to deal with this kind of uncertainty is to view it just that way: as uncertainty. You don’t know what’s going on in the person’s mind right now. Did they mean the phrase as a quick joke? Are they having a rotten day? Is this just how they communicate?

ToM allows you to realize that other folks could have impartial information. They might not know where the marble is, in other words. This kind of intellectual empathy dovetails nicely with the ability to forgive more of the things that bother you, as Hanlon’s Razor makes clear: never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

I might replace stupidity with inexperience with ToM. I think that’s exactly what happened to me on my first day of middle school, when I interacted with kids who were playing a more advanced game than me. A deep understanding of sarcasm just wasn’t there yet, and without understanding that someone can say something and mean something entirely different, you miss an opportunity to peer inside their minds.

Understanding is the goal, but even if you come a bit short of fully knowing what a person is thinking and why, you can still benefit from using Theory of Mind. That’s because you have much more of a tendency to give someone the benefit of the doubt, provided you simply try to figure out what’s going on in there.

Has a past version of you ever found yourself in a situation where Theory of Mind would have come in handy?

I’m gonna go ahead and say that someone has lost her marble!

This is all well and good but, like, where IS the marble?! You never told us the right answer!

Also...what's in the box? WHAT'S IN THE BOX?!