I was thinking about how important the DIY concept has been to me, and how to describe that history.

For most of our experience, Doing It Yourself was just considered doing it. People made the things they needed with the limited resources they had available, so there were lots of unique inventions and on-the-spot fixes in the world.

Gradually, centuries of standardization made the world smaller. Economies of scale allowed people to start producing things of the same size and shape at a scale never before imagined. Factories meant that the same goods could be rubber-stamped out to far, far more people with a lot less money and effort.

Now, everyone had the same stuff. This cookie-cutter abundance was a double-edged sword.

It made things easier to swap out or repair, and it made goods available to more people… but there was a downside that people began to call attention to, especially toward the end of the 19th century as Taylorism really kicked factory production into high gear.

Writers like Thoreau and Emerson had already planted strong seeds of doubt as to whether civilization was all it was cracked up to be, so by turn of the 20th century, there was already a mass movement flourishing in the US, standing against rote conformity. People began to reject the soulless nature of products everyone had. They would resist what they saw as the zombification of America by making their own stuff instead of feeding the machine.

Then, the Roaring Twenties happened.

Suddenly (maybe not that suddenly), the mindset had shifted in favor of mass consumption. Radio and mass marketing started to plant different seeds in the minds of listeners and readers. Propaganda had been perfected on Madison Avenue, and eager hucksters were ready to put these new tools to use.

It took a depression and a world war for the pendulum to swing the other way, but swing it certainly did. I was able to interview my grandfather for a school project some four decades ago, so I heard his story first hand. I also got to see the remnants of their DIY mindset, still very much intact when I knew them.

It was understandable that my grandparents had this mindset, even as late as the 70s and 80s—decades after the scarcity of resources had ended for the nation. Having lived in a time when throwing something away would certainly mean doing without, it was hard to change old habits.

So, the first Do-It-Yourself movement was a rejection of conformity, but the second was more about need. The third wave—the one I got to be a part of—was a blend of both.

This third DIY wave formed as a response to the return to zombification.

After the conclusion of World War II, there was the perfect storm for mindless conformity. First, everyone was incredibly united after having just beaten Japan and Germany, and having a strong feeling that everyone around you was on the side of freedom and democracy.

The perception of shared values and exhaustion from fifteen years of economic devastation and war, coupled with a sudden surge in prosperity, really set the conditions for an exhausted public ready for mass consumption.

By the time the internet was invented and Douglas Engelbart gave the Mother of All Demos, the pendulum had swung toward backlash. Nixon’s resignation surrounding Watergate and a nasty crash in the stock market led into a period of stagnation that was the dominant paradigm when I was born.

Right around this time, punk rock was also born. Punk was a completely countercultural movement that showed up at just the right time. The mohawks and boots became commoditized and commercialized during the 80s, but the punks I got to know during the early 90s were doing their own thing anyway.

For one thing, they would design ‘zines to sell or give away at shows. This meant self-publishing by literally cutting and pasting pieces of paper you wanted to be somewhere on a page, then photocopying that rigged template. When you turned the pages of a zine, you were looking at a copy of something handmade.

Zines were half art and half publication. You could easily get lost in the thoughts of someone else, and lots of different ideas could be shared this way. The best zines had lots of contributors, so you would get multiple viewpoints and observations from columns and interviews.

While the punk rock zines were motivated not to use the system, I was initially motivated because I was completely broke. This began in earnest at the end of 5th grade, when we didn’t have yearbooks, so we made our own:

See the MacMillan English book there on the back? I think that’s me wanting this to look as official as possible:

Clearly, I understood that you could make things yourself, and that there could even be value beyond what you could purchase by way of the system—mass manufactured goods, I mean.

I saw that Transformers could be made from paper and then traded for actual Transformers. The value of a commercial good was equal to the value of something I had made with my hands. That lesson really stuck with me.

Confidence grew as I created a zine that was an impromptu newsletter about my middle school. I know I shared this with my friend Tim and maybe a select group of five or six kids, but I created a full little magazine that included columns, a cartoon with characters I had made up, and even some fake ads.

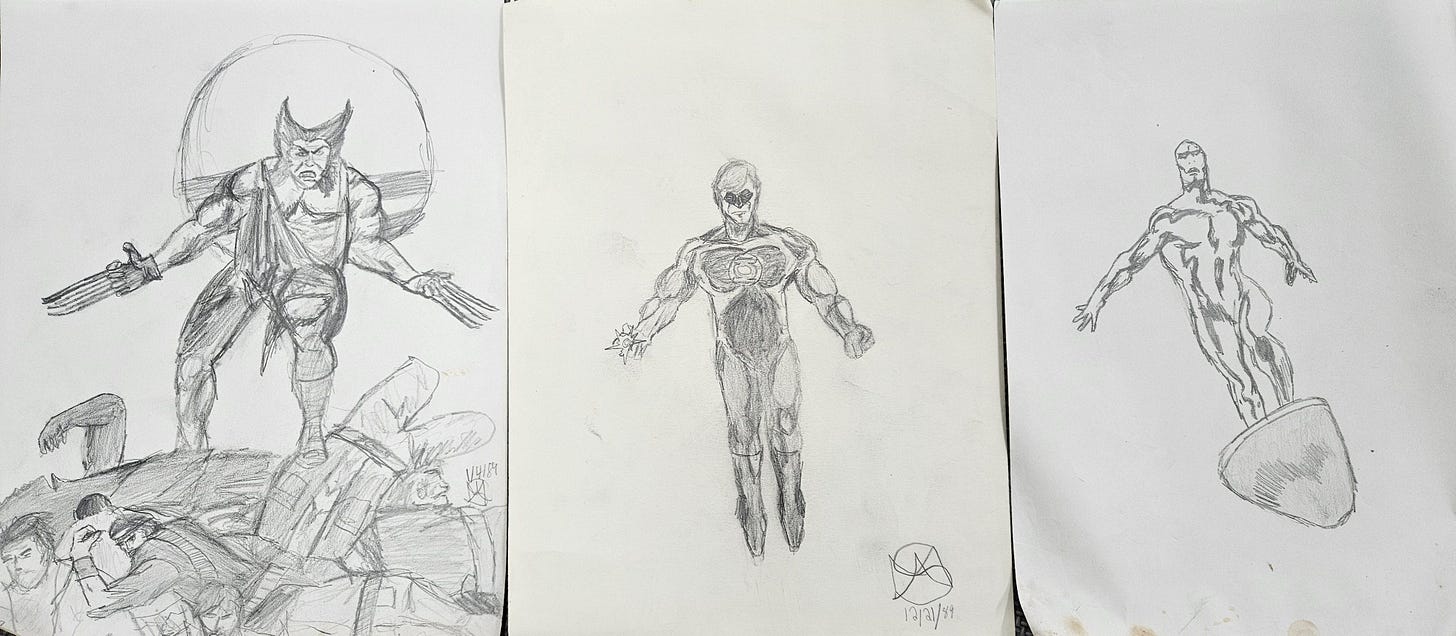

Necessity was the mother of invention, just as it had been with the original US DIY movement. I realized that I could draw comic book covers and use them as posters.

We created our own D&D campaigns out of whole cloth instead of buying modules, and then I created a role-playing game we could all play together, centered around the Werewolf universe from a TV show we loved.

All this creating and self-publishing made it easy for me to do stuff like interview the Misfits (the punk band) and a few other bands, which I then turned into a zine. Here’s that story, if you’re curious:

Meeting the Misfits

While Glen Danzig’s ego is inversely proportionate to his height, the Misfits remain one of the most popular and influential punk bands of all time.

This lent itself directly to early web publishing, where it suddenly became ten times easier to reach a large audience. When I built my first website in 1998, it was on Geocities, a DIY publication platform prominent at the time.

eBay was DIY for selling stuff. I embraced it lovingly, and it transformed my life. Clearly, it didn’t change who I was—self publishing, driven to make my own way in the world—but it made a lot of things possible.

It wasn’t easy to start any of the businesses I’ve owned over the years, but it was nevertheless natural for me. It is the DIY spirit that runs deep in me that opened these doors in the first place, and it is that same spirit that has me here, writing and publishing every day (going on 800 days in a row!). I get to say the things I want to say, in the manner I want to say them.

Now, there are certainly degrees of DIY, and I am certainly toward the lazier end of that spectrum. I still pay web servers instead of spinning up my own machine to host, and there’s plenty of arguments to be made that I’m merely supporting the system that a DIY lifestyle presumes to sidestep entirely. Fair!

Still, I can’t help but marvel at the secondary path that’s available. It’s not necessarily easier to self-publish, but it’s the only way I can imagine doing things these days.

Maybe it’s because I’m just a little older, but the late 1960s were a great time for DIY-ers. Tuning in and dropping out was all about forging your own path. Books like The Whole Earth Catalogue and Zen & The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance were all about countering the post WWII conformity.

Dude, I know all about DIY. I've personally built every item of IKEA furniture in our house. I'm practically MacGyver, basically.

Also, your childhood drawings would give anything I can produce today a run for its money.