The Stuart Period in England was full of surprises.

There was the early attempt at a large lottery, a desperate scheme to raise much-needed funds for the nation. There was a joint-stock company that didn’t really do anything, which nearly bankrupted the government.

Desperate times called for desperate measures, and things were indeed desperate for King Charles I during the fateful lead-up to the English Civil War during the middle of the 17th century.

Charles knew full well that there was one technological ingredient that could determine the winner or loser of any close conflict. That ingredient was gunpowder.

He who controlled the gunpowder controlled the guns, and recent conflicts had proven beyond all doubt how important guns were to winning wars. The Thirty Years' War on mainland Europe and the Dutch War for Independence were ongoing conflicts where battles were decided as much on the basis of firepower as on manpower.

Charles was less worried about these conflicts across the channel, though. He had his hands full with what would become a full-on civil war during his reign, and he could see this conflict coming. In order to prepare for the coming conflagration, Charles needed to produce an obscene amount of gunpowder.

Saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal.

That’s what you need to make gunpowder. England had plenty of charcoal because it had plenty of trees, so it was one down and two to go for Charles.

Sulfur didn’t exactly grow on trees in the British isles, but England had a good trading relationship with Sicily and other Italian regions with a volcano nearby. Sulfur mainly exists below the crust of the Earth, but volcanic eruptions bring mineral-rich magma to the surface, including sulfur.

That left saltpeter, the third necessary pillar. While sulfur comes from underneath the surface, and charcoal comes from trees, potassium nitrate (saltpeter’s chemical name) arose predominantly from decaying organic matter. This could mean a rotting corpse, but it was more likely to come from waste products like manure or urine.

Given that there were no large-scale production facilities for this type of thing—the Taylor system for running factories wasn’t going to be around for another 250 years—so Charles turned to something much older: crowdsourcing.

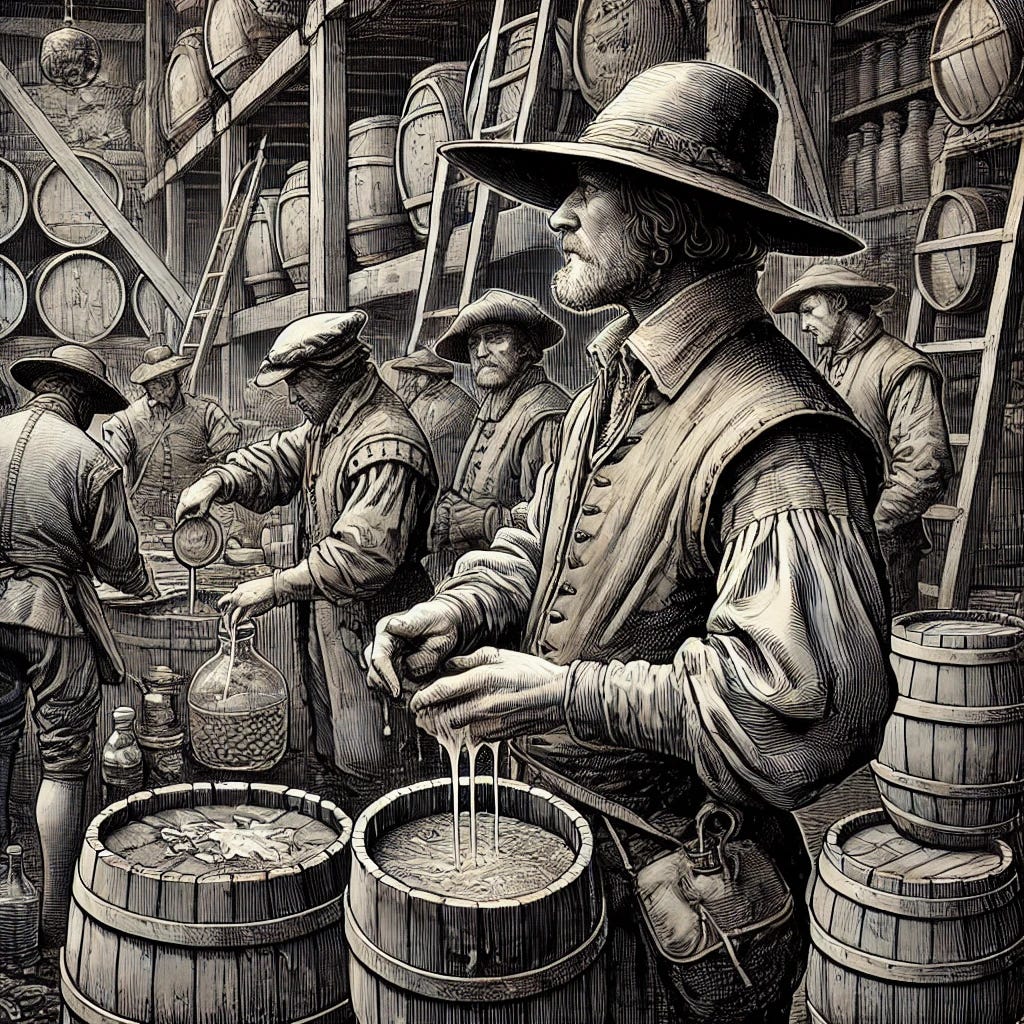

That’s right: in order to produce enough saltpeter, King Charles I of England ordered his subjects to save their urine. Subjects were expected to hand their waste over to the petermen or saltpeter men, guys hired by the Crown to go from house to house collecting waste (or, even grosser, to hunt through waste) in order to collect nitrate-rich materials like pee.

Sometimes, folks would take their chamber pots to a niter bed, which was a bit like a giant compost pit. Their waste would augment the enormous heap of decaying organic matter. The unpopular petermen were responsible for all of this.

This was fully expected civic duty, sort of like those Rosie the Riveter posters from World War II, but if they were about giving your urine to the King.

Believe it or not, this wasn’t the first urine-centric public works campaign in history.

During Emperor Vespasian’s time, the Roman Empire valued urine highly, but not for its saltpeter—gunpowder wouldn’t be invented for another eight centuries. In the ancient world, it was the ammonia that raised pee’s profile.

Ammonia made the ink more soluble, helping it bond better to fabric. This made for the boldest, richest colors sold anywhere, and you can bet this was a hot commodity. It’s also an incredible natural cleaning agent, and it’s useful as a catalyst when making soap.

Naturally, Vespasian wanted in on this action, so he taxed the fullers—the cloth cleaners who collected that liquid gold from public urinals all over town. The saying “money doesn’t stink” comes from this moment in our history.

One other saying also becomes much more clear when we remember the English petermen: “piss poor.” This specific phrase didn’t appear in print until the middle of the 20th century, but the idea that you might be so poor that all you could sell was your urine is a dramatic one, and it’s no surprise it has stuck in the popular mind.

Thank you for coming to my pee talk. If you want to read about poop next, you know where to go.

I salute you for putting "pee" and "hot commodity" so close to each other. Also, I'm impressed by your range - transitioning from poop to pee without breaking a sweat!

The waste products of many animals are used as fertilizer. Why should we view human waste any differently?