In 1889, the world was facing the future. Proto-computers were taking over the US census, the first working motion picture camera was in the process of being invented, and heavier-than-air flight was right around the corner.

Henry Balfour, by contrast, was increasingly obsessed with our past. After having been educated in animal morphology at Oxford, he pivoted to a career in archaeology, a really interesting convergence of two careers that offered Balfour some unique insights.

Balfour got a great job as the curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum, right there in the town of Oxford—a position he would hold for nearly fifty years. His focus was on the things people made over generations, and particularly the way in which tools had developed and evolved over the centuries.

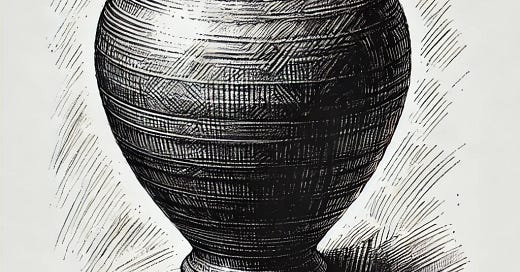

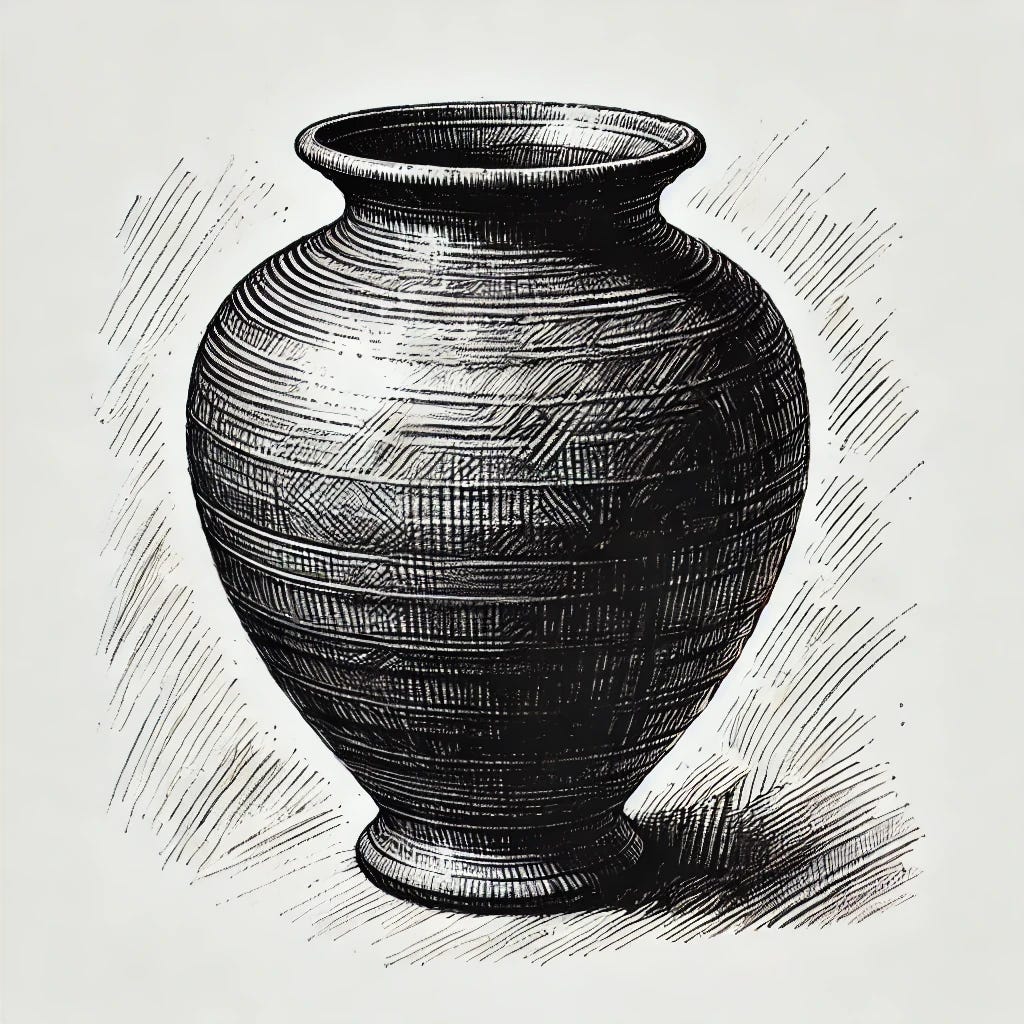

One aspect in particular became the subject of obsession: the ways in which some of these artifacts had retained previous features from an earlier form, even when those flourishes had become purely aesthetic. Balfour first noticed this phenomenon in pottery, where there was a curious design that seemed to mimic a basket’s weave.

There wasn’t any functional reason for the weave pattern, but curiously enough, this mimicked an earlier style that had been used, where baskets actually were used to shape clay into specific forms. In past generations, you would create a specific and accurate form by pressing the clay up against an already-formed basket, thereby creating a reliable and consistent supply of pottery products of a similar shape and size.

It made sense to see these patterns when baskets were needed to form clay into vessels, but better techniques had long ago taken over. The potter’s wheel and coiling techniques combined with better and better types of clay, and eventually baskets were no longer necessary.

Nevertheless, there that basket pattern was. How curious!

Here is where Henry Balfour’s deep knowledge of animal morphology comes into play. He was able to draw insights from evolutionary biology, where it’s incredibly common to find a descendent that retains some aesthetic remnant of a previous important tool.

Biologists call these vestigial structures (vestigium means footprint in Latin). Ostriches and emus have wings, but they can’t fly. Some snakes have little vestigial legs they can’t use—reminders of a time when their ancestors walked rather than slithered.

Even we humans have a noteworthy vestigial structure: we have a tail. It’s called a coccyx, and it really hurts if you land hard on it.

Balfour’s idea was that this sort of evolutionary phenomenon was also happening in archaeology, where vestiges of past functional techniques were evident. He coined a new word to describe this phenomenon: skeuomorph. It came from two Greek words, skeu (tool) and morph (form or change). Now, Balfour had a name for the phenomenon, making it easier to discuss this idea with other archaeologists.

Why should this woven pattern persist, though? With evolution, DNA simply expresses instructions to the cells as they are forming, so you get a lot of crude leftovers… but with pottery making, you have human minds guiding things along. What gives?

Well, for starters, we humans have a hard time of letting go of the past. It’s one of our defining characteristics, and cultural nostalgia is unbelievably powerful. It’s the reason I’ve written over 50 Substack pieces tagged with the word nostalgia.

It’s also entirely possible that someone wanted to identify themselves with a particular group, and a good way to do that would be to have a different pottery style. As usual, schismogenesis does the heavy lifting, as each side tries to outdo the other by differentiating.

They also might just look cool. I’ll sometimes keep things around simply because I like the way they look, and I like to hang onto things I enjoy seeing on a regular basis. It’s not very difficult to imagine the aesthetic appeal of the textured weave, contrasting with the smooth clay, might have held some cultural gravitas.

Today’s modern technology uses an awful lot of skeuomorphs. I opened today with three examples of cutting-edge, turn of the (20th) century tech, and I mentioned computers, video cameras, and airplanes. All three of these have vestigial remnants of earlier forms.

Remember floppy discs? Computers don’t use those any more, but whenever you save something, there’s often a little disc symbol, like this:

If you grew up in the 80s and you thought of an airplane, you almost definitely thought about rivets, those metal fasteners that are truly incredible at keeping perpendicular sliding from happening. You can still see these inside of lot of modern aircraft, and I think part of the reason is that they make people feel safe. You can see that it was made well, with a lot of forethought given to keeping the structure intact—or at least, that’s what they seem to say to me. Maybe

or someone else who works closely with aircraft can weigh in.And: video cameras aren’t big boxes like the original kinetoscope, but there are loads of features that give you the nostalgic feel of using a very old video camera. Phone cameras even incorporate a little mechanical shutter sound like you’d hear on a non-digital camera whenever you snap a pic.

These little skeuomorphs are everywhere in our modern world, and they’ve been a part of who we are ever since we started improving our technology. Have you noticed any of these little leftovers out there? What are some of your favorite skeumorphs?

You have many of those icons and sounds in modern software/hardware that are remnants of the past. The "traditional phone ring" that you can pick (or is sometimes default), the analog "alarm clock" icon. "Smiling person emoji," even though we've all forgotten how to smile in 2020. And so on.

(I was gonna bring up the floppy disk until you mentioned it, and then I was going to point out the camera shutter sound until you mentioned that too.)

I wrote a post about skeuomorphs last year, complaining about how they are such a problem https://lloydalter.substack.com/p/death-to-skeuomorphism